Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

A more Affordable aluminum bridging ladder

One of the most basic and effective tools for self-recovery in sand, mud, or snow is what we generically call the sand ladder or sand mat. For decades these typically comprised a cut-down section of WWII surplus PSP (Perforated Steel Planking, also called Marsden matting), originally designed to be linked together to build impromptu runways on boggy ground. Shoved edge on against a tire buried in sand, PSP provides a ramp on which the vehicle can gain traction and climb (especially when combined with some judicious pre-shoveling). PSP is effective but heavy, thus the popularity of a modern version—PAP—made from aluminum.

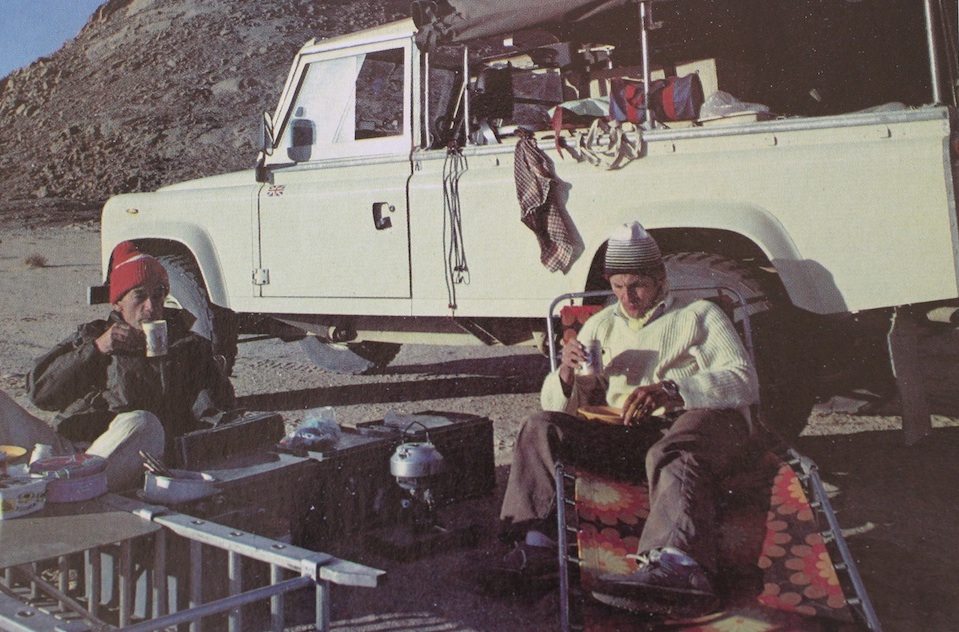

Semi-rigid material such as PSP and PAP works well to provide flotation and traction in soft substrates, but is not stiff enough to be used to bridge a deep ditch, or to function as a ramp to surmount a vertical ledge, unless doubled—in which case the normal complement of two allows only one wheel to be supported. Sahara explorer Tom Sheppard surmounted this problem decades ago by simply ordering a pair of custom-made ladder sections such as one would use at home, but with extra-deep side rails and rungs spaced just 15cm apart. Each section was sturdy enough to provide bridging support for one side of a loaded Land Rover—and with some connecting pieces also served as a convenient framework for kitchen furniture.

Today, plastic sand mats such as the excellent Max Trax offer a lightweight (18 pounds per pair) alternative to traditional versions; however, the Max Trax is still insufficiently rigid to be used as a bridging ladder unless doubled. The connoisseur’s choice for combined traction and bridging duty has for some time been the excellent Mantec bridging ladder (known as a bridgy by the abbreviating Brits), a beautifully trussed and welded structure of aluminum more than strong enough to support a fully laden expedition vehicle. But the Mantec ladders currently run about $650 per pair when you can find them this side of the Pond, and their bulk and weight—42 pounds for the two of them—is a handicap, too.

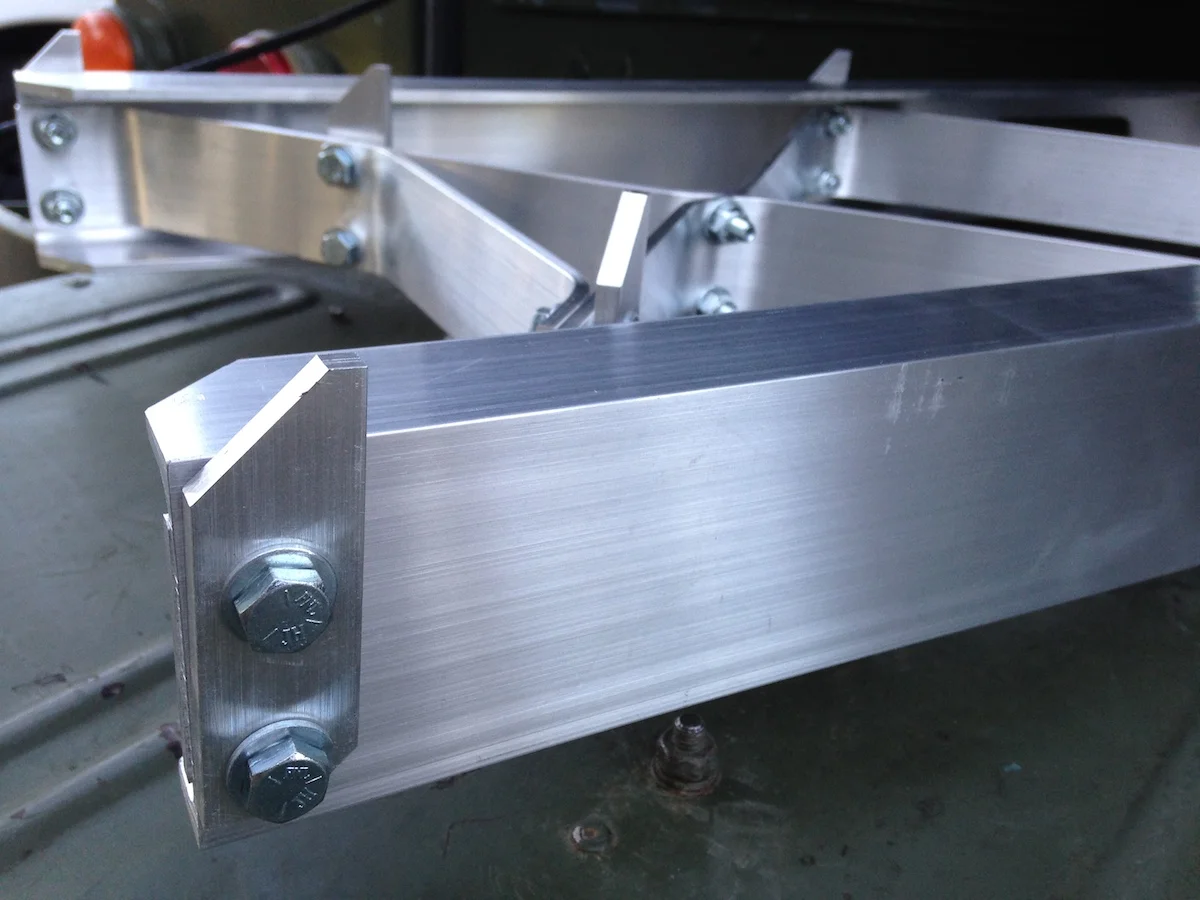

However, a significantly more affordable ($349) aluminum bridging ladder is on the horizon, thanks to Jeremy Plantinga of the newly formed Crux Offroad. Jeremy contacted me a year ago and showed me a few prototype designs before finalizing a design and shipping me this set—which comes disassembled via UPS, saving yet a bit more in shipping costs (a flat $30 to the lower 48).

The main structure of the Crux ladder comprises two 48-inch-long U-shaped side channels and two W-shaped cross treads, with a brace at each end and a total of 12 aluminum grip spikes that extend beneath the rails. The ladder is designed so the tire contacts the cross treads only after passing the ends of the side channels, to reduce the chance of kick-up. The instructions say assembly takes about an hour; I did the first one in 25 minutes and the second in 20. The side channels can be assembled with the U either in or out, depending on the width of your tires—with the U facing in the ladders appear more than wide enough for either the 235/85x16 ATs on our Tacoma or the 255/85x16s on the FJ40. The modular design means it will be easy for the company to tweak dimensions for different applications.

Mantec on the left, Crux on the right

In a quick visual comparison the Crux ladder lacks the monolithic support of the Mantec. It's obvious the Crux will offer less flotation in very soft sand, mud, or snow; on the other hand its open cross treads should significantly enhance traction and reduce kick-out when climbing. At 34 pounds per pair the Crux ladders are 20 percent lighter than the Mantecs (although they are also 20 percent shorter). Last year on the Continental Divide, when an FJ Cruiser pulling a trailer got stalled on some uphill ice, a pair of Max Trax we deployed simply zipped right under the tires when power was applied; the plastic offered no purchase against the ice. I’m willing to bet the grip spikes on the Crux ladders will do better in the same situation. For bridging, Jeremy rates the Crux ladders at 2,000 pounds each, which, given the insight I’ve had into his failure testing, seems appropriately conservative, and more than enough to support most full-size pickups, or a Land Cruiser or Jeep Wrangler Unlimited. Jeremy has plans to develop accessories such as table or bench tops and legs, which would enhance their versatility.

I’m looking forward to field-testing the Crux ladders, and expect they’ll perform well. If you’re intrigued too, they will be debuting and available at the Overland Expo in Mormon Lake next month. I plan to hand over my set to the Camel Trophy blokes to see what they can come up with for on-site testing.

The company's nascent website is here.

Update: I've had a little time to play with them. Supporting the front wheels of a Defender 110 in the middle of the span, the Crux ladders showed essentially zero deflection. Impressive . . .

Another update: The Crux ladders nest securely, located by the traction spikes. When joined, the adjacent handle holes make it easy to carry both ladders with one hand.

The irrational Land Rover . . .

I knew a fellow, a lives-and-breathes-them Land Rover aficionado, who was on his way across Africa in a 109 Station Wagon when the rear differential blew. Someone on a forum, as I recall, referred to the event in terms of a “breakdown”—which elicited an aggrieved response from the owner. This was not a “breakdown,” he insisted. Why? Because differentials are “maintenance items.”

If you are a lives-and-breathes them Land Rover aficionado, or if you know one, you’ll recognize this syndrome. Over the years, and to a greater or lesser extent depending on the model, Land Rovers have become known for being, how shall I put this . . . co-dependent. Because of this, owners are constantly besieged with quips, snarky comments, and jokes. (“Eight out of ten Land Rovers ever made are still on the road. The other two made it home.” Etc.) These are especially likely to come from Toyota owners revelling in their own brand’s sterling reputation. Desperate-sounding ripostes about Toyotas being “appliances” only come off as desperate-sounding—the Toyota owner just smirks and leaves the Land Rover owner grinding his teeth.

Perhaps it was the resulting Maginot mentality that led to the simple defense of not acknowledging breakdowns as breakdowns, and not calling repairs repairs. After decades of association with Land Rover owners, I’ve realized that the word ‘repair’ should not be applied to any procedure being performed on one of their vehicles unless they’ve rigged a steel beam on two A-frames extending side to side through both open doors, and are using three pulley blocks and a team of donkeys to remove something. And even then: A dear (nameless) friend whose Defender’s transmission failed on an epic trans-Africa trip actually excuses it with, “It wasn’t the vehicle’s fault. A part was installed incorrectly at the factory.” Um, okay, Graham. The reductio ad absurdum of this peculiar mental illness is reached when the poor owner begins typing spluttering forum posts such as, “They’re only unreliable if you don’t use them hard enough!”

I can write this without (much) fear of assassination because I have always felt a strong attraction to Land Rovers, and at the moment own two of them. At the same time I can keep one eyebrow raised ironically because I also own an FJ40 Land Cruiser that in 35 years has not once, one single time, left me stranded. In 1978, when I bought it, my choice was between the Toyota or a 1974 Series III 88, at that time a product of the troubled British Leyland group (‘troubled’ and ‘British Leyland’ being completely redundant phrasing). Everyone short of the State Department warned me off the Land Rover, and in retrospect buying the FJ40 was absolutely the right choice. Reliability aside, towing a 21-foot sailboat or a utility trailer loaded with eight sea kayaks would have been problematic with the 88’s 75 horsepower. And then there were those axles . . .

The logical choice . . .

Where was I? Right: The big question, of course, asked by everyone who is not of the lives-and-breathes community, is why? Where does what seems like this blind devotion come from, when there are so many alternatives, however appliance-like they may be?

One simple answer on logical grounds would be that Land Rovers work so well when they work that owners are willing to put up with constant fettling. From the range-topping Range Rover, still unmatched in its combination of luxury and off-pavement prowess, to the Defender, still unmatched in its combination of pliant ride with outstanding cargo capacity, and fine turbodiesel power with excellent fuel economy, Land Rover has been ahead of other marques in numerous engineering details since the 1970s.

But that’s the logical answer, and logical answers are vulnerable to logical ripostes regarding . . . reliability—surely, many would point out, the most critical characteristic of any expedition vehicle.

I think the real answer to the unswerving loyalty of Land Rover owners is the intangible, but undeniable, aura of history and romance that surrounds the Land Rover as it does no other expedition vehicle. Hook up electrodes to the brain of the most loyal Toyota/Nissan/Ford/Jeep owner, and ask him to, quickly, picture a vehicle on an African safari, and I guarantee the diagnostic screen is going to produce an image of a Land Rover, roof rack loaded with jerry cans, plowing through the bulldust of Tanzania.

The romantic choice . . .

Whatever the real reason is, I consider myself immune to such blind unreasoning justification.

Or, I did. Until this weekend.

I drove our recently acquired ex-MOD 110 Defender out to our desert property to do some work on the camping area. On the way out I’d noticed the shifting of the LT77 five-speed seemed to be more recalcitrant than usual (it’s due to be replaced with a later R380, along with a 300Tdi powerplant, soon). Just as I pulled up to park near the cottage, I was suddenly presented with, in the immortal words of the late James Hunt, a gearbox full of neutrals. Uh oh.

I had no factory manual, and no experience with the LT77, so I just got out the tools and began fettling. With the rubber shift boot pulled off, it became obvious the issue lay beneath a shift tower that supported two springs which helped locate the shift lever. With the springs popped off to the side, the lever came out (sending another spring-loaded plunger smartly across the cab, fortunately found). Four bolts undid the tower, and with it off the problem was immediately apparent: The metal and nylon socket into which the lever’s ball fits had come off the operating shaft, in turn because a set screw had come loose. Slide the socket assembly back on, tighten the set screw, tower bolted back in place, shift lever in and springs prized back on, and we’re finished. More or less precise shifting back in operation.

And then it happened.

I was thinking that, if the problem occurred again, I could probably have it sorted in less than 10 minutes. And as I innocently, happily considered that, another thought flowed—smoothly, sinuously, completely unbidden—into my brain:

It hardly even counts as a repair.

I’m doomed.

Or maybe I'm just not using it hard enough?

The Wescotts return from The Silk Road

One day in the summer of 1993 Roseann and I were sitting in a café in the Canadian Inuit village of Tuktoyaktuk, 200 miles north of the Arctic Circle. We’d been having one of those time-warp conversations with a phlegmatic local whale hunter: He’d ask a question such as, “Where you from?” We’d answer, there’d be a two-minute silence, then, “How’d you get down the river?” We’d answer, then ask him a question: “Lived here long?” Two minutes, then, “Born here.” We were in no hurry, having just paddled sea kayaks 120 miles to get there, so it was a fun way to pass time and—slowly—learn something of the area.

After a while a couple came in—anglos, surprisingly, the first we’d seen since landing the day before. They sat nearby and said hello, and we struck up a conversation that must have seemed alarmingly hasty to the Ent-like whale hunter. They asked how we’d got to Tuk, and when we described our trip expressed open-mouthed admiration. They’d flown from Inuvik, it developed, and had left their pickup and camper there.

And as soon as they mentioned a truck and camper, I realized that the couple was Gary and Monika Wescott. It was my turn to be open-mouthed, as I’d been reading tales from the Turtle Expedition in Four Wheeler magazine for, what, 15 years already by then? I’d devoured the articles documenting the extensive modifications to their Land Rover 109 during the 1970s, had been disappointed but intrigued when they switched to a Chevy truck (which, even more intriguingly, vanished without comment soon after), and then followed the buildup of the Ford F350 that would prove to be the first of a series. Our Toyota pickup had a Wildernest camper on it at the time, but we were saving to buy a Four Wheel Camper of the same type that sat on the F350 Turtle II. Most recently, I’d read along as the Turtle Expedition completed an epic 18-month exploration of South America.

We saw each other over the next couple of days as we all took in the annual Arctic Games, watching harpoon-throwing contests and blanket tossing, and snacking on muktuk. Then we lost touch for 15 years (while they journeyed across Russia and Europe), until reconnecting when I edited Overland Journal.

Since 2009 the Wescotts have been regular instructors and exhibitors at the Overland Expo—until 2013, when they embarked from the show on their latest adventure, a two-year trans-Eurasian odyssey along the Silk Road.

Now we’re delighted to welcome Gary and Monika back from their journey. They will be giving presentations and taking part in roundtables at Overland Expo WEST 2015. Don’t miss a chance to meet these two personable and friendly travelers. Listening and watching as the Wescotts describe their journeys is both entertaining and inspiring, and their latest journey should be fertile ground for good tales.

Best of all, Gary and Monika are genuinely excited to share; there’s not a trace of bravado between them, despite being among the most-accomplished overlanders in the world (and still traveling). They travel because they are passionate about exploring and learning and sharing, not because they are trying to count coup or gain fame. It’s refreshing, and we are glad to have them back.

- Regional Q&A: Russia, Mongolia & Southeast Asia; Friday 2pm

- Regional Q&A: Europe, Eastern Europe & Iceland; Saturday 8am

- The Silk Road; Saturday 11am

- Experts Panel: Top Travel Tips; Saturday 1pm

Explore 40 years of adventures with the Turtle Expedition at http://turtleexpedition.com

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.