Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

Sneak Preview: Schuberth E1 helmet

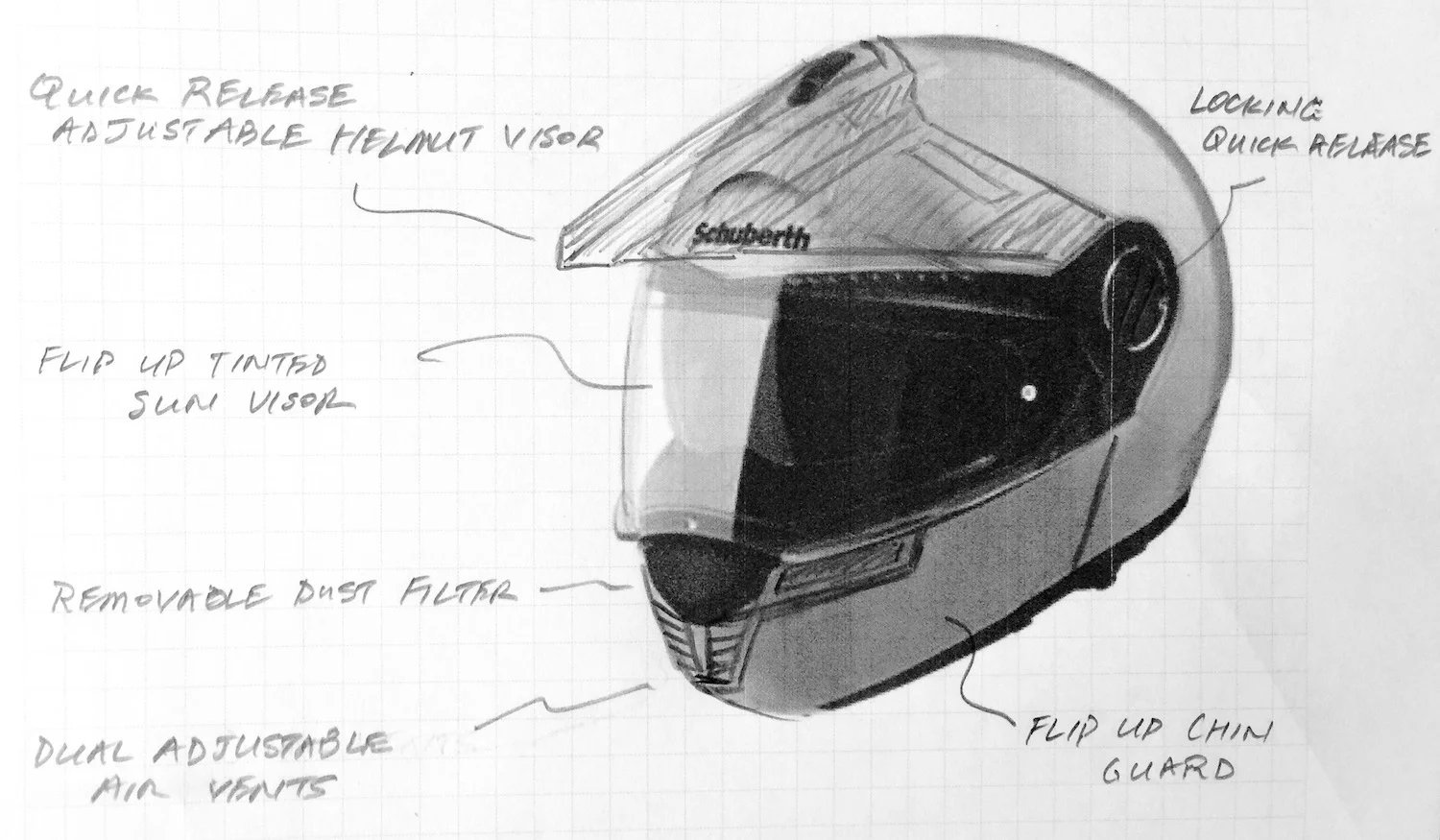

Illustration by Jonathan Ehly

Special report by Carla King

Schuberth unveiled its new adventure helmet last night to a crowd of motojournalists in a hangar in Irvine, California. We had to swear not to leak photos, but were given free reign to describe it otherwise. The shortest description I have for you is simply that we will all want to be wearing this helmet next year.

The new Schuberth E1 adventure helmet is based on their C3 modular design, with an adjustable peak visor and a filtered breather at the chin, as illustrated in the sketch above. Both the visor and the filter can be easily removed.

I’ve worn the Schuberth C3 for over three years now. It's the top of the line in safety and comfort in a modular design. (See my July 2013 story Schuberth C3 helmet: 12 months and 10,000 miles review.) It has a flip-up chin guard, integrated flip-down sunglasses, and air vents at the chin and top that really work, providing air flow all around the head including down the back.

In my three-year experience with the helmet, all of its claims hold true. It’s light and quiet (thanks to an acoustic collar and anti-noise pad) and directionally stable, with no buffeting or oscillatory tendencies. It doesn’t fog up (Pinlock Visor) or roll off (Anti-Roll-Off System) and the COOLMAX inner lining is smooth, comfortable, breathable, allergen-free, antibacterial, and hand-washable.

The new E1 adventure helmet enjoys all the great features of the C3, plus a quick-release, removable and adjustable helmet visor and improved ventilation and dust filtration. Here’s a shot of the profile of the new helmet clipped from my badge.

The peak visor sports generous air vents to avoid drag when riding fast. It is also adjustable, allowing you to tilt it high so that it’s barely visible or down low over the eyes when chasing the sunset. An auto-lock keeps it in place it no matter how many times you ratchet the chin guard up and down.

Removal of the peak visor happens with a quick twist of the quick-release screws on each side. Replace the holes with the included plugs and you’ll hardly know they were there in the first place.

The dirtbike-style venting for air flow is substantial, jutting slightly out the front of the chin guard with a lever that allows you to adjust the air flow. The removable filter—a quarter-sized puck that you can rinse out—fits snugly into a cavity inside the chin guard. Inside, there seems to be plenty of room for the kind of heavy breathing induced by off-road conditions. I can’t wait to put it to the test.

The graphics are exciting and unique, with patterns and colors to fit every style. Among the designs are color blocks of high-vis yellow and a stunning indigo (also offered in yellow and silver color block). My personal favorite is a design of scratchy, black and white vaguely zebra-esque brushstrokes on a background of hi-vis white with a yellow band. There’s also a red, white and blue swirl.

The target market is the safety-conscious dual-sport adventure motorcyclist who can afford the estimated $800+ price tag. Details will be officially announced, along with photos, at the Schuberth E1 helmet’s official release at AIMExpo in Orlando, Florida, October 15-18.

Carla King's website is here.

Thinking outside the box

For a short time after I got out of college, in the mid-1980s, I sold Toyotas for a living to pay off student debts (I was pretty sure I wouldn’t be doing so working as a freelance writer . . .). When talking to customers about Toyota trucks or the Land Cruiser, I always made sure to point out the fully boxed frame, and contrast it to the open C-channel frames then standard on American pickups. In those days you commonly saw Chevy and Ford trucks with the cab accent line offset from the bed line by an inch or more, due to frame flex that eventually settled in permanently. I’d take the customer on a demo drive, and put one front wheel up on a high curb to get a rear wheel off the ground, then show them the bed perfectly aligned with the cab. If they still had any doubts, I showed them a stack of articles I’d saved from the local newspaper, which covered the massive problems the Arizona Game and Fish Department had been having with their current issue half-ton Chevrolet trucks—cracked frames and broken motor mounts had reduced the serviceable numbers in the fleet by almost half.

At that time, the corporate line from Ford and Chevy was, “The frames are designed to flex (Italics mine) to maintain a comfortable ride and keep all tires on the ground as part of the suspension design.” Riiiiight.

The magnitude of the about face in the last 20 years would be amusing if it weren’t so annoying. Beginning in the late 90s and this century, American pickup manufacturers began producing (and heavily hyping) frames with higher and higher levels of torsional rigidity, culminating in the splendid fully boxed chassis now standard on all half-ton Ford, Chevrolet, and Ram pickups, and being introduced on 3/4 and 1-ton models as well. Even some crossmembers are boxed these days, in addition to being formed along with the side rails from high-strength and ultra-high-strength steels. Clearly the Big Three discovered that they could maintain a “comfortable ride” and still build a stronger, more durable truck.

It’s all over their ads these days:

Here's Chevy promoting the new boxed frame on its 3/4-ton pickup:

Meanwhile, over at Toyota . . .

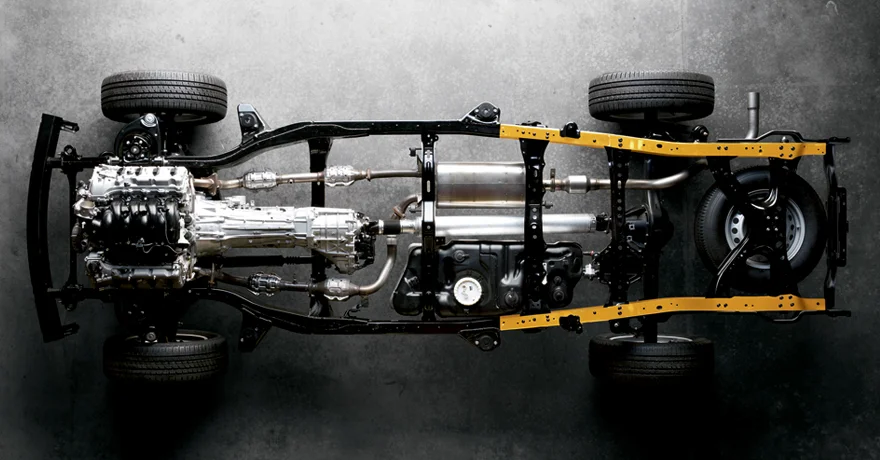

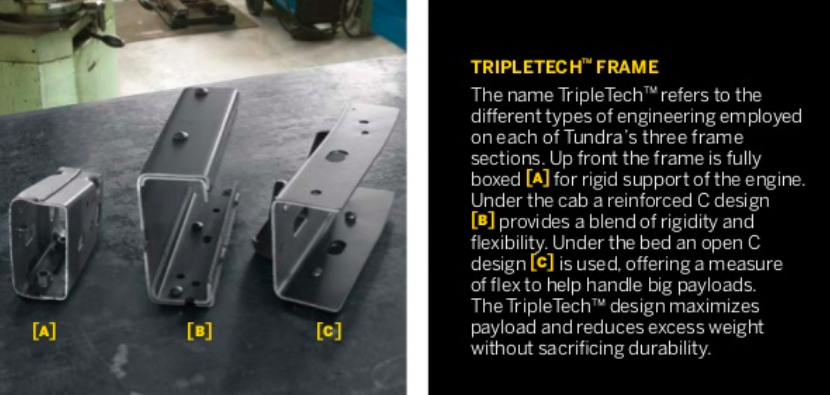

First, the full-size Tundra arrived in 2008 with a foundation grandly described by the company as a “Triple-Tech” frame—which, as I wrote about here, turned out to be an open C-channel frame with a bit of boxing under the engine. Next, the second-generation Tacoma was introduced. Gone was the fully boxed frame that had been under every compact Toyota truck for four decades; in its place was . . . an open C-channel frame with a bit of boxing under the engine. The redesigned 2016 Tacoma retains this configuration.

Toyota’s explanation for this? I’m paraphrasing various official websites and quotes to several reviewers, but the gist is accurate: “The frames are designed to flex (Italics mine) to maintain a comfortable ride and keep all tires on the ground as part of the suspension design.”

Let's parse the caption in the ad above. First, Toyota tells us that the front of the frame is boxed for "rigid support of the engine"—obviously a heavy item. Then they tell us the rear of the frame is an open C, "offering a measure of flex to help handle big payloads." Okay Toyota, so what if I want to carry, say, an engine in the bed of my truck? And that middle part cracks me up. A "blend of rigidity and flexibility." So, it's . . . sorta rigid?

There’s a back story here that I believe might be behind this. Many of the fully boxed frames under first-generation Tacomas and Tundras developed severe rust problems, to the point that Toyota has paid to have thousands of them replaced, at no-doubt hideous expense. Toyota blamed the problems on sub-standard steel from a provider, but there was little doubt the issue was, at the very least, exaggerated by water getting trapped inside the frame rails. I wonder if Toyota execs decided to eliminate that problem and save money at the same time by switching to an open-channel frame and tagging it with a fancy name.

Let’s be clear—a boxed frame is better in virtually every way than an open-channel frame. The strongest structural member there is is a tube. That’s why race cars and race trucks are built with tubes, not open C-channel members.

The proper place to engineer suspension compliance is in the suspension, not the structure responsible for supporting both the suspension and all the running gear and bodywork on the vehicle. The Toyota Land Cruiser (including the pickup) and Hilux, the Land Rover Defender, the Mercedes-Benz G-Wagen, the Jeep Wrangler—all employ fully boxed frames. So does the new Chevrolet Colorado, set to take a chunk out of the Tacoma’s market share. The military’s HMMWV? A fully boxed frame.

Heck, even HMMWV scale models have fully boxed frames:

In fact, the only exception I can think of in high-quality four-wheel-drive vehicles is the Mercedes Unimog, the chassis of which has deliberately been engineered to incorporate a degree of flexibility. Suffice to say that the massive Unimog is dealing with an entirely different set of parameters than a half or 3/4-ton pickup (as are oft-referred to semi-truck trailers).

Proponents—or apologists—point out that the steel in open-channel frames is thicker than that in boxed frames. To use the vernacular: Duh. It has to be thicker to maintain even a semblance of rigidity. You could argue that an open-channel frame is intrinsically more resistant to rust, given the thicker material and the lack of potential crannies to trap water and crud. But Toyota’s failures along these lines don’t mean boxed frames are inferior, simply that those particular frames were not designed properly to keep out water or to let it drain. For proof look at all the other boxed chassis on the market with no such problems, and indeed Toyota’s own earlier trucks that had no issues.

Some claim that boxed frames are heavier, which is simply untrue. A boxed frame can actually be made lighter than an open-channel frame of identical torsional rigidity.

The only legitimate advantage to an open-channel frame (besides, obviously, lower cost) is that it is simpler to bolt things to. There’s just a single thickness of steel, and easy access to drill and place bolts and nuts to attach anything from a bracket for a suspension air bag to a replacement utility cargo bed. On a boxed frame you must drill through two thicknesses of steel a couple inches apart, and use much longer bolts. A minor and infrequently encountered issue for most of us.

I’m curious—apprehensive might be a better word—to see what Toyota does with its next generations of U.S.-spec trucks. Now that the company has gone down the open-channel “better than a boxed frame” path, it would mean a loss of face to go ‘backwards’ to a better design. (Think the next Hilux will show up with an open-channel frame? I bet not.) The irony would be thick if the company that showed U.S. manufacturers how to build a better truck frame fell permanently by the wayside in competitive design.

There's an old saying that is doubly appropriate here: "Sometimes it's good to think outside the box. Other times it's better to stay in there and have someone tape it shut."

The new Tacoma's new engine

The introduction of the redesigned 2016 Toyota Tacoma seems to have been more cloaked in secrecy than any new-vehicle release I can recall. Details have trickled out of the company slower than Hillary’s emails. (Just hand over the server, Toyota!)

One of the biggest questions concerned the optional V6 engine. We knew it would be new, but information regarding power and other specifications was not to be had. Now at last we have details.

Basically, the 2GR-FKS is a 3.5-liter (3,456 cc) 60º V6, with double overhead cams and four valves per cylinder, derived from the engine in the 2015 Lexus GS. Bore and stroke are 94 and 83mm. It produces 278 horsepower and 265 lb.ft. of torque—up 42 hp and, er . . . down one lb.ft. from the previous 4.0-liter 1GR-FE V6. Its most intriguing design feature is the fuel injection system, which combines port (fuel injected into the intake manifold just above the intake valve) and direct (fuel injected directly into the combustion chamber) operation. At low speeds, the system can combine both injectors or use one, as needed, to provide stable cold starts, prompt response, and low emissions. At high speeds and high loads, the system switches to direct injection: Each cylinder is equipped with an extremely high-pressure injector that sprays atomized fuel in a horizontal fan-shaped pattern into the combustion chamber after the piston has begun its compression stroke. This promotes a complete burn, reduces detonation, and cools the intake charge, enabling a very high 11.8:1 compression ratio while retaining the ability to run on regular gas—thank you Toyota! (Direct injection is promoted as the latest in high-tech engine wizardry; in fact the 1954 Mercedes-Benz 300SL had it, albeit with mechanical rather than electronic control.)

Toyota refers to the 2GR-FKS as an Atkinson cycle engine, which technically it is not. The original Atkinson-cycle engine used a complex multi-piece connecting rod that enabled a complete intake, compression, combustion, and exhaust cycle to be accomplished in one turn of the crankshaft (rather than two as in a “normal” Otto-cycle engine). It also, cleverly, allowed the intake/compression stroke to be shorter than the combustion/exhaust stroke. The Toyota system uses a much simpler modified Otto-cycle process in which the intake valve is held open for a period after the piston has begun its compression stroke, allowing some ‘leakage’ back into the intake manifold. This reduces the effective compression ratio and charge volume—which seems like a bad thing—but retains the full expansion volume of the piston’s combustion stroke. Simply put, this allows the combustion process to extract more energy from the intake charge, increasing efficiency and fuel economy. (There is a good YouTube video here.) However, there is a downside: Since this process is compressing less fuel and air per stroke than a standard Otto-cycle engine, the power density is somewhat lower. I’m guessing (yes, guessing!) that given the variable valve timing capabilities of Toyota’s VVT-i cam system, the “Atkinson cycle” effect can be varied or even turned off as required by engine speed and load, but I’ve not yet confirmed this.

Internals of the 2GR-FKS engine are of superior quality. Block and heads are aluminum, of course. Both the crankshaft and connecting rods are forged. The cams are driven by a long-life chain rather than a belt, and the rocker arms ride on needle bearings. Iridium-tipped spark plugs are good for 60,000 miles, and have a deep threaded section, which allows thicker material in the head at that point, which in turn allows coolant passages to be routed closer to the combustion chambers. Externally, the exhaust manifolds and pipe are stainless steel.

The aim of all this, of course, is the holy grail of improved power with lower fuel consumption. Indeed, the city and highway economy ratings for the 2016 Tacoma are better than those of the outgoing model, despite the increased horsepower. However, they still lag behind the figures for the 3.6-liter V6 in the new Chevrolet Colorado—which also boasts 305 horsepower. (And—sigh—let's not even mention that truck's optional 2.8-liter Duramax turbodiesel.) We’ll have to see how real-world figures compare to the EPA’s estimates.

One more item is worth mentioning. When I heard the new Tacoma’s engine was to be a 3.5 liter, I wondered aloud if its torque peak would be at an even higher engine speed than the already too-high 4,000 rpm of the outgoing 4.0-liter. Sure enough: The 2GR-FKS delivers its 265 lb.ft. at a stratospheric 4,600 rpm. Compare that to the 4,000-rpm peak in the Colorado—or the 2,000-rpm torque peak of the inline six-cylinder in my old FJ40. Those few who choose the manual transmission and decide to haul a loaded trailer with their new Tacoma are going to be doing some serious revving to get under way. As my friend and ace Toyota mechanic Bill Lee said when we were discussing this, “I love doing clutch jobs.”

A match for cotton, at last?

I’ve always been a stalwart defender of cotton clothing for hot-weather wear. Nothing else felt as comfortable or kept me as cool on desert treks ranging from my Arizona back yard to the Namib. Occasional forays into the world of synthetics invariably ended in disappointment—manufacturers’ claims that their exclusive formulations of nylon or polyester were “as comfortable as cotton” simply did not hold up, and struck me as ironic: If you want a fabric “as comfortable as cotton,” why not simply wear cotton? (Sort of like the soy burgers that through cunning combinations of spices try desperately to taste like beef.)

I was well aware of the incontrovertible advantages of synthetics in terms of their quick-drying properties—a benefit for active situations in which the fabric is likely to become soaked with either perspiration or water, as well as for washing clothes in the field. But those did not outweigh the harsh feel of the fabric against my skin. Likewise, the purported superiority of synthetics in wicking moisture away from the skin seemed advantageous for cold-weather base layers but unneeded in hot weather, when cotton’s absorption properties got that moisture to work providing evaporative cooling, and the chill feel of the wet fabric actually felt good on a 100ºF day.

After I posted my brief experience with the (all-cotton) Avedon and Colby Field Shirt (here), I got an email from Adam Rapp of Clothing Arts, makers of the Pick-Pocket-Proof line of trousers and shirts. Once again, Adam’s assurance that his nylon fabric was “breathable and comfortable, unlike most synthetics” left me dubious, but I was happy to try the shirt he offered to send, if only to look forward to dismissing it as yet another almost-but-not-quite ersatz cotton.

And . . . the shirt I received had a “hand”—clothier talk for feel—virtually indistinguishable from cotton: soft, pliable, with a brushed finish that had none of the slightly “snaggy” feel of my previous experience. I tried it on, and the impression held; it felt like a cotton shirt. (In small it also, wonder of wonders, fit my frame—the company offers a wide range of sizes.)

Designwise, I appreciate the simplicity of the PPP shirt—no fancy vents and mesh capes (which always made me ask in the past, why are such things needed if this fabric is so great?), no too-small sleeve pockets, no non-functioning epaulettes. Instead, behind the two basic chest pockets are two concealed zippers that access security pockets behind the main ones. Brilliant—a hold-up artist doing a visual check would miss them entirely. Collar tabs help the collar keep its shape. My only complaint is the shirt’s tails, which are on the significant short side for staying tucked in. (Well, one other: Like all synthetic shirts, this one seems to stain permanently more readily than cotton. The available khaki color would be a better bet for most field use.)

So standing around in the PPP shirt gave no indication that it was anything but cotton; how about moving around outside? I wore the shirt on a morning bicycle ride in Tucson’s summer. After 20 miles the temperature had hit the low 90s, I was perspiring freely—and the shirt felt great. I can’t say it felt like cotton; it was not necessarily worse, just different. A cotton shirt would have felt wet, and the evaporative cooling would have been noticeable as cold wetness against my skin. The PPP shirt wicked well; the result was that my skin felt dryer, giving the impression that I was not as cool. However, the shirt dispersed the moisture so effectively that evaporation was if anything probably greater than in a cotton shirt. As I said, different. Anyone looking at me in both shirts would have immediately noticed a difference: In, say, one of my Filson Feathercloth shirts it’s immediately apparent I’ve been sweating from the darkened wet areas; the PPP shirt by contrast appears dry.

Although this shirt isn’t made specifically for water sports, I nevertheless took it kayaking down the Potomac River, where nylon’s superiority to cotton is inarguable: Even though by the time we hit the take-out the shirt was quite wet from splashing and paddle drips, before we had the boats and equipment put back in the truck it was completely dry.

My conclusion? The Pick-Pocket-Proof shirt is very, very close in hot-weather comfort to an all-cotton shirt, even for my atavistic tastes. Combine that with nylon’s fast drying properties, making it an excellent choice for traveling, and I feel I’ve at last found a viable alternative to cotton in an outdoor shirt.

Postscript: Adam also sent me a pair of Pick-Pocket-Proof pants, of which all the things I’ve said about the shirt also apply. The pants are offered in your choice of both waist and leg sizing—increasingly rare in the world of outdoor clothing—and in a range that starts slimmer than my own size and goes up from there. Three cheers for Clothing Arts. Last but not least, the anti-pick-pocket features are really effective: It takes concentration and a half a minute to retrieve a wallet from the hip pocket past the two buttons and the zipper that guard it. Even Apollo Robbins might have a tough time taking your money.

Clothing Arts is here. The PPP shirt is a reasonable $70; the trousers are $125, or $110 if you don't need the convertible-to-shorts feature.

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.