Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

When equipment makers go under

Recently the overlanding forums have been buzzing—steaming might be a better verb—with the news of a bankrupcty filing by a (formerly) respected maker of aftermarket bumpers and skid plates—and the concomitant loss of the deposits of a good number of innocent customers.

Similar sagas have followed an all-too-common pattern. A company with a solid reputation for quality overextends itself with the orders flowing in after many positive reviews from journalists and previous owners. First it can’t keep up with production, and deliveries fall behind. Zealous overspending early on—a bigger factory, a new truck (or house) for the owner—now means that incoming deposits are used to purchase materials for products that were ordered months before. Cash runs short, then out altogether. By the time enough customers realize what’s happening and post warnings on relevant forums, dozens of later customers are already out of luck as well. And throughout it all the company’s website stays active, inviting the unaware to click “Buy now,” in a desperate bid to get more cash to try to catch up with a cascading backlog of production.

This has happened before in my experience with companies servicing the overlanding market—once with a maker of top-of-the-line bumpers and roll cages for Land Rovers and Ford trucks, once with a very high-profile manufacturer of luxury truck-based campers. Given the exploding popularity of overland travel and the associated equipment (and the Great Recession that hit just as the activity was gaining traction), I’m surprised it hasn’t happened more frequently—businesses go out of business while making money all the time, due to other factors that can range from poor management to the management snorting the profits or letting it ride on 32 red.

The reasons are of little concern to those who have lost hundreds or thousands of dollars after placing a deposit or even paying in full for a product they have every expectation of receiving in a reasonable amount of time.

What can a consumer do? In most cases, thorough prior research into the company’s reputation will suffice, especially if you look up current forum posts regarding their products and customer service. Don’t look at only one thread or jump to conclusions from one post—just as there are customers with legitimate complaints, so are there trolls whose mission in life is to complain and badmouth in an attempt to make others as unhappy with life as they are.

Once you’ve committed to ordering a specific product, basic steps to protect yourself should be mandatory. Be sure all your correspondence with the company is in writing (email is fine), including specifications, final price, and, above all, a final delivery date. Consider negotiating a discount if delivery is late.

However, despite precautions there is always the chance you’ll be caught at just the wrong time, after trouble starts but before it becomes widely known. The next best defense is to use a credit card with a strong buyer-protection plan for any deposit you are required to put down. We once paid several thousand dollars to a service company that utterly failed in its promises to us. Fortunately we had used an American Express card, and when we provided complete documentation of the issues and our attempts to rectify them, we received a full credit from Amex.

Without a guaranteed way to recoup your money from your end, your chances of doing so from the company can be slim. If there are bankruptcy proceedings in court, you can bet the banks, steel suppliers, and landlords will get their claims way higher on the list than your piddly little $1,000 deposit.

Thankfully such situations are rare. But it’s always smart to practice due diligence.

The new ARB hydraulic Jack

It’s been a century and a decade since the Automatic Combination Tool, as the Hi-Lift jack was originally known, was introduced by Philip John Harrah, founder of Bloomfield Manufacturing. And for that 110-plus years, nothing else has achieved the versatility and capability of the Hi-Lift. It will raise two and a quarter tons anywhere from 22 to 46 inches in one continuous operation, depending on the model selected (36, 42, 48, or 60-inch). It can be used as a clamp, a spreader, and a winch. Its various parts have been employed as bodge fixes on countless broken vehicles—I used the tubular handle of one to sleeve a broken tie rod and get an International Scout back to civilization.

However. For all its strengths, the Hi-Lift has some significant issues. The most salient among them is that, if used carelessly, it has the capability to break any number of body parts on that user, from fingers to jawbones to skulls. When the operating lever is under tension (either lifting or lowering) it is extremely unwise—let’s just say stupid—to stray into the arc between it and the main beam. The Hi-Lift is heavy at 30 pounds for the popular 48-inch model. Finally, it is prone to jamming when exposed to road dirt, although a quick dousing with any spray lubricant will usually clear it.

And yet, surprisingly few attempts have been made to improve on the Hi-Lift (the raft of outright copies don’t count, of course). One attempt I tested about seven years ago (here), the Radflo Hydra-Jac, showed promise, since it operated hydraulically and there was no risk of kickback on the reassuringly small operating handle. And the Hydra-Jac weighed just 13 pounds. However, its lifting range was a relatively modest 18 inches, the round base was far too small, and, much more importantly, the jack’s capacity was a measly 2,200 pounds. It would barely get the front of my FJ40 off the ground; our Ford F350 would have laughed at it.

Enter the brand-new ARB JACK. That’s right, simply “jack” in all-caps. I hope no one got paid to come up with that. But let’s forgive them for the moment and look at the product. Note, however, that I will refer to the product as the ARB Jack, just one capital, because as a writer and grammarian I refuse to empower this lamentable trend toward all-cap product names (MAXTRAX, GLOCK, etc. etc.). You know those annoying people who post in forums in all-caps so it sounds like they’re YELLING AT YOU? That’s how I feel about all-cap product names.

Where was I? Right:

Like the Hydra-Jac, the ARB Jack is hydraulically operated. Distinctly unlike the Hydra-Jac, the ARB is rated to lift a proper, Hi-Lift-like 2,000 kilograms (4,400 pounds, and tested to 7,000). Furthermore, it will lift that 2,000 kg a full 48 inches off the ground. That’s 10 inches more than a 48-inch Hi-Lift. Yet when compressed the ARB is just 36 inches long. In its heavy-duty case our test sample fit easily crosswise behind the seats of our Troopy with room to spare. Impressive.

If that’s not enough to convince you this jack is a contender against the long-reigning heavyweight champion, note that the ARB Jack weighs just 23 pounds, a useful 25-percent reduction. Also, the handle of the ARB is not prone to flopping loose as the Hi-Lift’s handle will if you don’t have one of those polyurethane keeps slid over it. Combined with the short compressed length, this makes the ARB far easier to handle than a 48-inch Hi-Lift.

Last bit of empirical information: The ARB Jack can lift in precise 1/2-inch increments, unlike the larger jumps necessitated by the Hi-Lift’s climbing pins. And the ARB’s lowering lever (which takes a one-finger press to operate) has two speeds, so gentle or swift dropping is your choice. Literally effortless compared to lowering with a Hi-Lift (which is actually its most fraught procedure since if control is lost on the operating lever it can slam up and down in a violent feedback loop).

So far this sounds like a nearly complete shutout for the ARB Jack versus the Hi-Lift. But—we might as well get this over with now—there is an 800-pound gorilla in the room. Or, to be precise, an 812-pound gorilla, because the U.S. list price of the ARB Jack is $812. For that much cash you could buy yourself and seven friends a 48-inch all-cast Hi-Lift.

Is the ARB Jack worth it? After trying it out briefly on a trip through Australia, I’d say it depends on you. If you own a Hi-Lift that never comes off the roof rack or that pedestrian-mangler mount on the front bull bar, then you’d just be showing off to switch to the ARB. And I doubt many people will be mounting such a thief magnet to the outside of the vehicle anyway.

On the other hand, if your Hi-Lift is rusty, its red paint nearly gone, its jam-prone mechanism lubed over the years by everything from WD-40 to beer; if you’ve forgotten how many times it’s extracted your vehicle or that of a complete stranger, if it’s caught you out and smashed a finger or bruised a hand or worse, and if every time you use it you treat it like a capable and strong pack mule that hates your guts and is just waiting for a chance to kick your head in, then you might find the ARB Jack to be a bargain.

Nine slots facilitate easy adjustment of the tongue height.

I used the Jack to raise the rear end of our Land Cruiser Troopy (via the dedicated jack slot in its Kaymar bumper, which the jack’s tongue fit perfectly), and immediately noticed the first advantage of the ARB over a Hi-Lift. When you lift the tongue of a Hi-Lift to fit into a bumper, you’re reducing its total lifting capacity by the height of the bumper. Not so the ARB Jack. Instead, the tongue itself slides up the jack and engages one of nine slots in the anodized aluminum alloy body, leaving the full lift capacity intact. Thus, although the total lift distance of the ARB is less than that of a 48-inch Hi-Lift, it will raise the vehicle higher. Only when lifting something from ground level will the Hi-Lift better it.

Only 36 inches tall stored, the ARB Jack will lift to a full 48 inches.

The next thing I noticed was expected, but still revelatory: Pumping the actuating handle is way, way easier than operating the lifting handle of a Hi-Lift. It’s much shorter and thus cannot exert the same leverage—but it doesn’t need as much leverage because the magic of hydraulics is doing much of the work for you. The back end of our Troopy is not exactly light—in addition to our pop-top camper unit, fridge, and cabinetry we have a 90-liter water tank and a Long Ranger 180-liter fuel tank closely tucked around the rear axle—but the back came up with remarkably little effort. I’ve taught Hi-Lift technique to a lot of people, and those under 140 pounds or so—men or women—often have trouble raising a very heavy vehicle, even with proper technique. They’ll have no such trouble with the ARB.

The short lifting handle is easy to operate, with zero chance of kickback.

To lower, simply press the red lever.

As for lowering—oh my is it easy. Lowering a weight with a Hi-Lift requires exerting exactly the same force one used to raise it, with the added risk of that feedback loop if one loses grip on the handle. Not possible with the ARB. Just press the little red lever with one finger, and down it goes, slow or fast, your choice; all at once or a half-inch at a time, your choice. Brilliant.

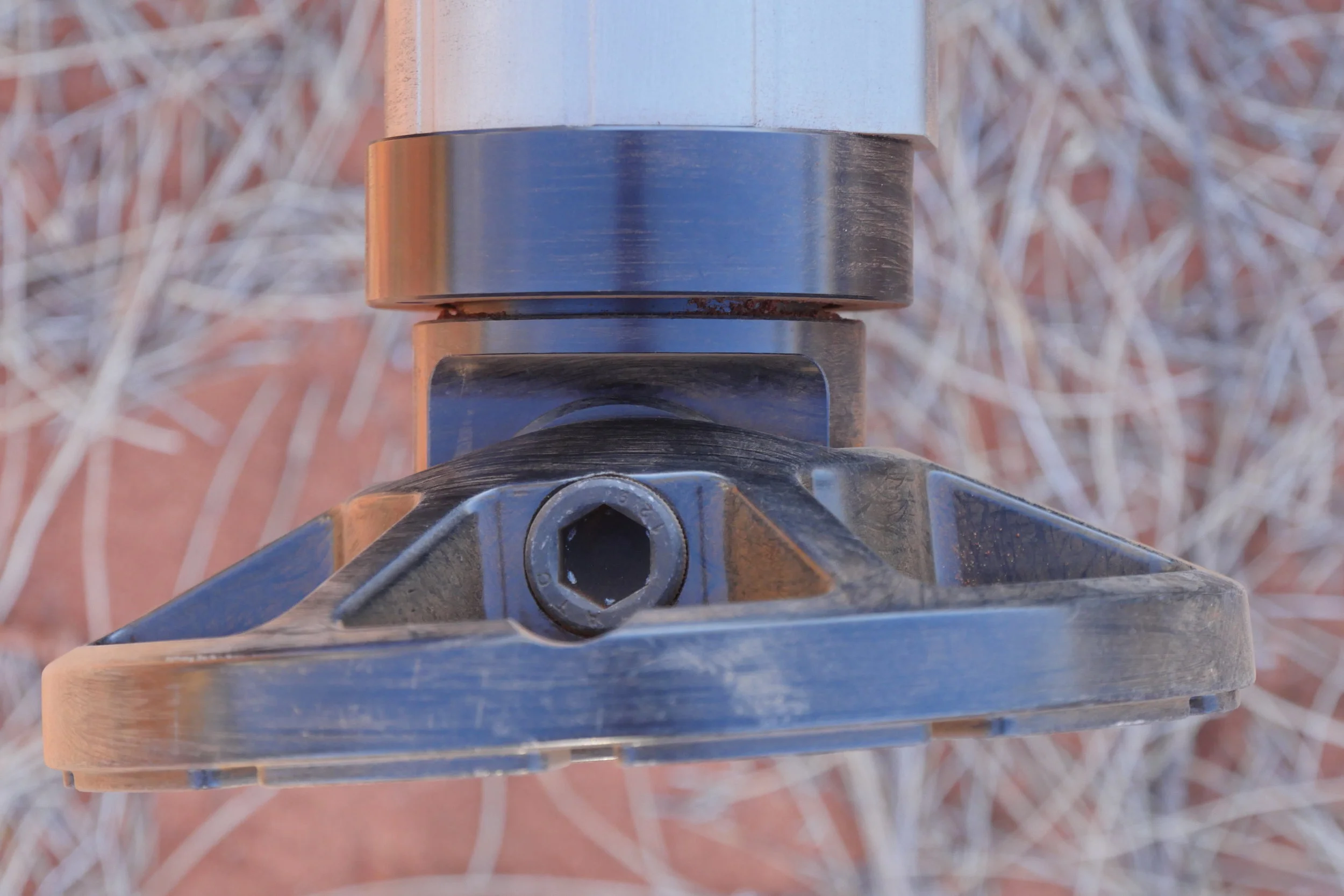

A heavy-duty ball joint allows the base to tilt about ten degrees.

Another aspect of the ARB revealed itself in the red sand of Australia’s Great Victoria Desert. Its mostly round base has more area than the rectangle of a Hi-Lift (34 versus 28 square inches), but it will still sink in soft substrate. Attempting to raise the Land Cruiser in sand resulted in more downward movement of the base than upward movement of the vehicle. And that round base does not fit in the rectangular receptacle of the standard red plastic jack base. I expect someone will quickly rectify this issue; in the meantime it would be easy to fab up your own from three layers of 3/4” plywood, with a cutout in the top layer to secure the base from sliding.

One characteristic of the ARB Jack did prove to be a bit of a pain. When you lower a Hi-Lift and the load on the tongue is relieved, the tongue and lifting assembly automatically drop free. With the ARB, once the load is off there is still considerable hydraulic resistance in the piston; lowering fully requires keeping the red lever pushed all the way down while leaning on the jack with enthusiasm—and it won’t happen quickly. I think a significant upgrade to this tool down the road would be a switch that engaged a bypass valve to completely (or nearly so) release the pressure. Such a switch would need to be covered to prevent accidentally pushing it when a load was supported. But it would rectify my sole complaint about the ARB Jack’s operation.

Graham tries futilely to hurry the lowering process . . .

. . . while Roseann takes her time.

Some people with whom I’ve discussed the ARB Jack have brought up the inevitable argument: “Can you winch with it? Can you clamp with it?” To which I ask, how many times have you winched or clamped with a Hi-Lift jack except to try it? I can answer for myself: zero. I’d bet a lot of cash that an exceptionally tiny fraction of Hi-Lift owners have ever used theirs in anger as anything except a jack.

The rubber sleeve slides up or down to protect the vehicle's sheet metal.

Conclusions? The ARB Jack is distinctly superior at its primary function of jacking, compared with the Hi-Lift and its many copies. It’s lighter, it’s easier to handle, it takes much less effort to raise a vehicle and literally no effort to lower it, it is significantly safer (although obviously safety depends heavily on the operator for either product), and it is much easier to store.

It remains to be seen if the ARB Jack will prove as durable as the Hi-Lift, many of which have been going strong for decades. The slowness in lowering once a load is removed is annoying but definitely a first-world problem. (Still, it would be nice to see a relief valve added at some point.) I have little doubt aftermarket companies, and ARB itself, will soon fill the gap for expanded bases and other accessories.

Fine sand can collect against the piston seal. Best to keep this clean.

The sole remaining issue is that 812-pound gorilla. When I (reluctantly) turned in the jack to the ARB dealer in Perth, the manager told me they’d been selling every one they could get. So perhaps in this current overlanding world of $2,000 fridges, $4,000 roof tents, and $20,000 adventure trailers, an $800 jack is going to be no big deal. If you’re considering one, I can at least assure you that it will work as advertised—it is a very, very fine tool.

ARB Jack: $812. Leaving a stylish brand in the Australian sand: Priceless.

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.