Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

The Toyota Hilux gets . . . gasp . . . rear disc brakes

Toyota has announced a new Hilux model, the Rogue—naturally not for us, just our lucky Down Under mates. Along with 140-millimeter-wider front and rear tracks, the Rogue will finally shoulder its way out of the pre-Cambrian muck and be fitted with rear disc brakes, as every competitor has been for at least the last ten geologic epochs.

You might have read my comments on the 2016 Tacoma and its retention of a century-old braking system, along with Toyota’s fatuous justification for keeping them, way back here. The world-market Hilux also remained stuck with rear drums. Now, finally, Toyota has leaped into the latter half of the twentieth century—at least on this version of the Hilux.

Will the Tacoma follow suit? I cannot imagine Toyota keeping up the charade that “drum brakes are better off road” for much longer.

Will an upcoming Tacoma also benefit from a return to a fully boxed chassis, as the Tundra has done (and the Hilux has retained all along)? Or is that too much to ask?

Cross-winding synthetic winch line—yea or nay?

Like more experienced people of my acquaintance (you know who you are, Jim), I’m hyper-vigilant about spooling my winch lines correctly.

There are solid practical reasons for this: A winch line that is spooled neatly, tightly, and under load is far less likely to kink (if steel) or snarl, and there is less risk of the line diving down through the wraps below during a strenuous recovery. A neatly and tightly spooled winch line is smaller in overall diameter on the drum than a loosely and sloppily spooled line, thus retaining more of the winch’s rated power. During most straight winch pulls, a properly spooled winch line will practically re-spool itself automatically as it follows the path of least resistance across the drum. Finally, if you’re ever forced by circumstances to pull out your line all the way down to the bottom layer during a recovery, those tightly spaced first few wraps are less likely to slip.

However, I have to admit something: There’s also a significant OCD component to my own diligence. I can’t sleep when I get back from a trip or training until I know that winch cable is restored to perfect alignment. A winch cable lined up in snug parallel rows like a Marine drill team—or the Rockettes, take your pick—just looks so much better than, well, this:

Please pause while I catch my breath.

(Of course, ironically, a winch that’s been bolted on strictly as a poseur accessory, with factory-spooled line, will look just as tidy. We must then count on our frayed and faded Dyneema and well-burnished eyelet or hook to set us apart as real users.)

For years I preached the gospel of properly spooled winch line—at the Overland Expo, during NPTC evaluations, in private training sessions, and on guided trips. The total of my converts surely rivaled that of an obscure middle eastern carpenter from a few centuries back.

Then, recently, horror struck.

On a random day on a random overlanding forum, I came across a post titled something like “Cross-winding your winch cable.” The author of the post—clearly a goat-horned demonic agent sent from the Underworld—claimed that by spooling one’s winch cable in great angled swoops across the drum, the chances of the line diving were eliminated, since the line was never layed parallel.

There was a photo.

OMG.

My stomach lurched. My pulse jumped. It was . . . indescribable. Lazily spooled winch lines were nothing compared with this . . . this deliberate travesty.

Staring at the awful image, I tried to calm myself. With shaking fingers I straightened my computer on my desk. I straightened my phone. I lined up my pens, my flashlights, my knives. They were all already straight but I straightened them again. I re-coiled my Macbook’s power cord into a perfect whorl. Was my desk crooked? I nudged it into perfect alignment with the floorboards.

It didn’t help. I needed a drink. I stumbled to the kitchen. Daiquiri? Its elegance and mathematical symmetry (2:1:1) beckoned. Clumsily I gathered the components—no, this was taking too long. I flung the top off the crystal decanter and chugged directly. Rum ran down my chin and spilled onto my shirt, onto the countertop. I licked it up. Oh the degradation. I tried to slow my breathing.

Okay . . . better.

Back at the computer, I replied to the goat-horned demon, politely, that no one should consider trying such a “technique,” and that no professional would recommend it.

The GHD responded, “Oh really? How about this then?” And included a link to a page on the Samson Rope website.

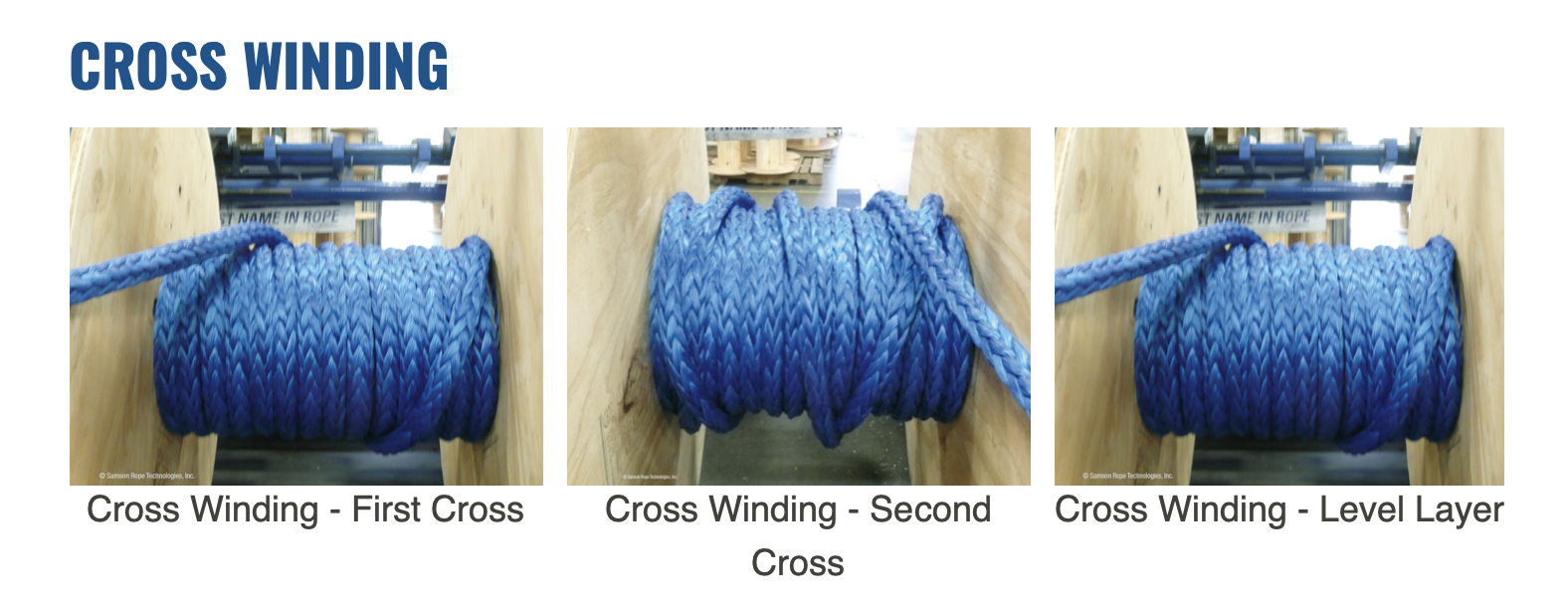

I felt a queasy stirring of doubt, but clicked on the link—and there, on the website of one of the most respected makers of rope and winch line on the planet, was a series of photos explaining how to cross-wind synthetic winch line when spooling it.

I wondered briefly if nitroglycerin pills were available over the counter.

Instead I looked around the web, and found another reference to cross-winding from the Australian company Schillings, and in fact uncovered mentions of the practice in forum archives from over a decade ago.

Okay. Deep breath. I firmly escorted OCD Jonathan outside and locked the door, then sat down and thought critically about this technique. As the Samson site described it, you wind on two layers of line in the normal fashion, then drag the line across the drum as it spools, creating two layers of criss-crossed line. Then two more flat layers, then more criss-crossing, until the line is fully spooled. All in an effort to prevent the winch line diving between layers when under a load—which, it seemed on the surface, it might accomplish.

Or would it? Given the instructions to alternate two layers of parallel windings with the crossings, it would still be critical to ensure those parallel layers were tight, or your criss-crossed line would still happily dive between them as it was pressed into the spool when one of the parallel layers above it was pulled tight under a load—perhaps creating an even worse snarl. Additionally, the Samson instructions specified “50 pounds of tension.” That’s not very much—when I respool I employ a minimum of several hundred pounds of tension.

I thought some more. First, I noted that I have never personally had a winch line dive between layers with my “normally” spooled winches, nor have I seen it happen on winches belonging to the far more experienced people I’ve had the luck to train with and learn from. This led me to believe that, except in rare circumstances, the problem was only a problem with poorly spooled lines—i.e. spooled with insufficient tension—and that someone who experienced it because of poor technique and adopted cross-winding as a fix would probably experience it even with cross-winding.

Second, it’s obvious that cross-winding will take up more space on a winch drum than parallel winding, reducing the power of the winch with each unneeded layer, and requiring more line to be pulled off the drum to achieve the same strength. Also, how could you possibly neatly wind two parallel layers atop two cross-wound layers?

There are other issues. In a side-pull scenario, when the criss-cossed layer is uncovered I’d expect the line to jump across the drum with some force, at minimum creating a sharp jerk in what should be a smooth operation. Also I’d expect line speed to increase and decrease as either a crossed line or a parallel line is tensioned.

In the end I remained firmly unconvinced, if not actually calling BS. But was I now an outlier? A dinosaur? I sent the Samson link around to a few friends and associates, including luminaries such as ex-Camel Trophy team members. No one who responded thought cross-winding made sense. Andy Dacey, a director at Wildtrackers in the UK, who not only trains military units in four-wheel-drive techniques but is also a forester and thus extremely familiar with ropes and rope handling, believes the Samson page is aimed at those who spool their winch lines by hand, under very little tension—thus the “50 pound” reference. He also noted that a line under high tension pulled over the line one layer lower at near right angles would put extreme stress on one point, flattening it there. (If you use a synthetic-line-equipped winch frequently, you might notice the lower wraps sometimes look strangely squashed; doing that across the line doesn’t seem like a great idea.)

Andy told me he has no intention of cross-winding his winches. Any of them.

I don’t either.

Now if you’ll excuse me I have to go let OCD Jonathan back in.

He’ll be relieved.

Easy, Jonathan. For illustration purposes only.

Ratcheting screwdrivers, Husky versus Wera

Until last month I’d never bought a ratcheting screwdriver.

Why? I’m not exactly sure. Perhaps I distrusted the mechanism and preferred the extra (assumed) reliability of a standard screwdriver. Perhaps out of a misplaced sense of purity.

In any case, recently I was faced with the fun but monumental task of duplicating, as much as possible, my entire Tucson tool collection for our new place in Fairbanks. Obviously this involved a whole bunch of compromises, since we’re talking about a decades-long accumulation. And it will have to be accomplished incrementally, the most critical tools first. But the cabin needed several important repairs and upgrades, so I had to cover the basics quickly.

Screwdrivers were high on the list. I’d brought a few with me in the cargo trailer in which I hauled our furniture and household goods, but I needed a selection of bits for some weird fasteners I’d found in the cabin. At the Fairbanks Home Depot I found a $20 Husky ratcheting screwdriver with a selection of bits stored in the base of the handle, and decided to try it.

It didn’t take long before I discovered the advantages of the concept. It wasn’t always advantageous, and frequently I left the ratcheting mechanism locked out, but in certain circumstances it made inserting or removing fasteners much faster and more convenient. I was definitely sold on the concept.

However. The Husky tool itself proved problematic. First, the ratcheting mechanism felt coarse, which meant wasted motion turning it back and forth as the excess slack had to be taken up each time—even when it was locked. Much worse, however, was the bit storage, accessed by a ribbed cap in the base. Illogically, the cap was tapered so you pulled on the narrowing butt of the grip, backwards for optimal use. It was so hard to grasp that I took to opening it with my teeth. And it didn’t open smoothly but with a jerk—which meant that half the time it maddeningly spit one or several bits out onto the floor. Do these companies ever conduct beta testing?

Sigh . . . Wondering if there was something better, I did a search, and . . . aha. A German company with which I’m familiar, Wera, made one, model KK 27 RA2. For, naturally, two and a half times what the Chinese-made Husky had cost. Nevertheless, I ordered it. Sadly by the time I did so I was due to leave Alaska for Tucson, so I had it sent south. Thus I have no side by side photos (although thanks to the magic of digital publishing I can edit later).

So, is it two and a half times better than the Husky? Maybe not—the Husky, after all, will do the same job—but it’s satisfyingly way better. The ratcheting mechanism is much smoother and finer, and the bits are held securely in the center of the grip, accessed by a sliding port activated by a button at the end of the grip. Both complaints about the Husky solved—and, in addition, the Wera has a much nicer grip and a stronger magnet to secure the bits. It’s a joy to use, rather than merely okay. The Wera has become the screwdriver I reach for first for many jobs, both household and automotive.

Transglobal Car Expedition gets a lesson in global warming

Back in March of this year I was horrified and angered to read the following headline on the Explorers’ Web:

“Transglobal Car Expedition Loses Vehicle Through Ice; Local Inuit Village Outraged.” (Read the article here.)

The vehicle was a Ford F150 prepared by Arctic Vehicles, first known for their fat-tired Icelandic Toyotas. The truck was part of a seven-vehicle fleet conducting a test run for something called the Transglobal Car Expedition, the stated purpose of which is to cross both geographic poles by vehicle, all on the surface (that is, no flights, only ship transport when necessary). The website also says— quoting verbatim here—“We believe that we can embrace the Earth by meridian by meridian and unite people all over the world in one common journey.” (The rest of the site exhibits similar egregious editing issues. End snark.)

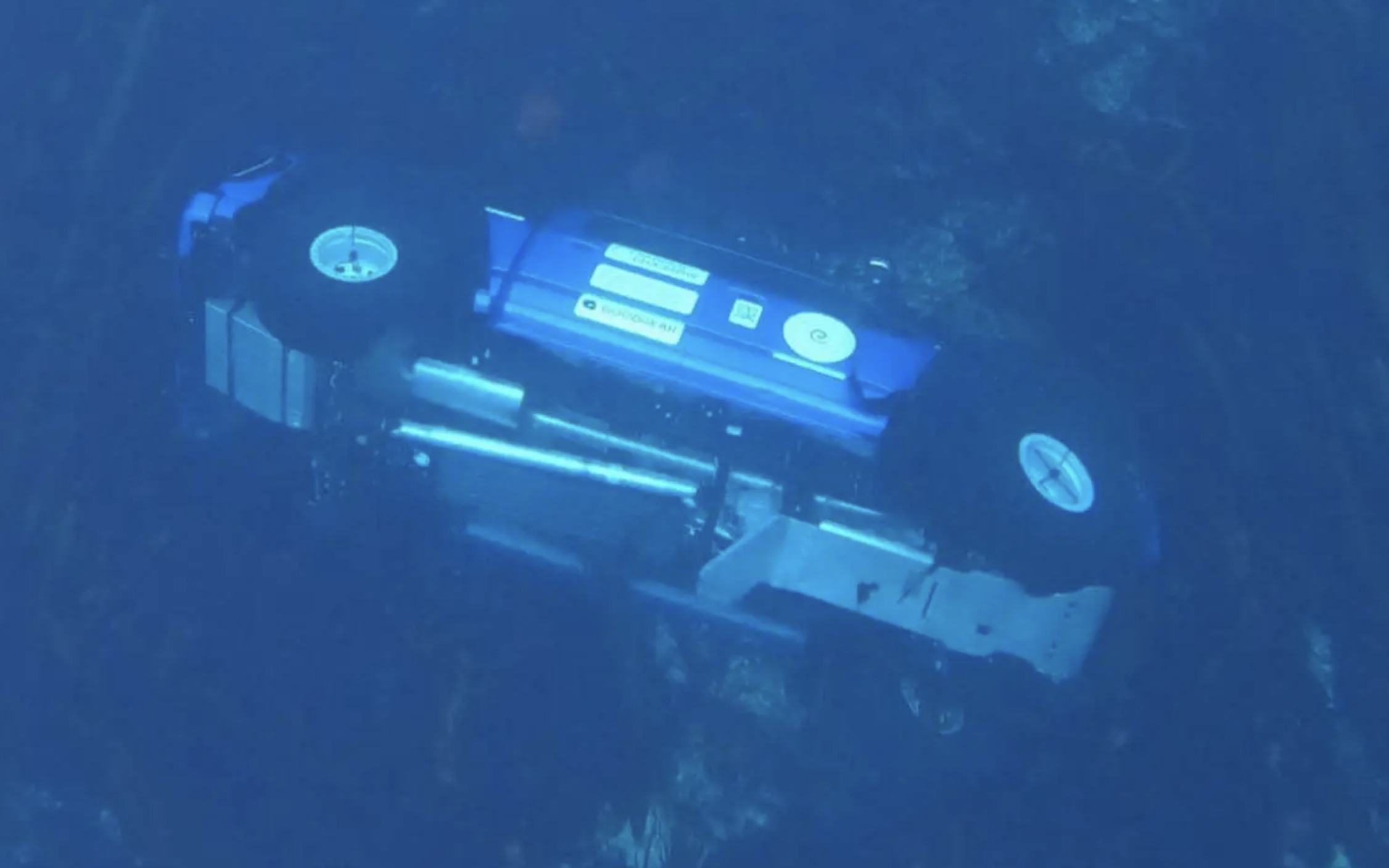

Unfortunately, on this “common journey,” while crossing sea ice off the northwest coast of the Boothia Peninsula, in Canada’s Arctic, the truck broke through thin ice and began sinking. The crew was able to escape before the truck plunged the rest of the way through and went to the bottom in about 30 feet of water—while carrying “40 liters of fuel,” a backup generator presumably carrying its own fuel, plus of course the engine and transmission oils and fluids. (I wonder if the “40 liters of fuel” actually refers to jerry cans, and doesn’t include fuel in the main tank.)

The irony here is significantly thicker than the ice through which the truck sank. An expedition in the process of burning tens of thousands of gallons of fossil fuel to “embrace the earth” loses one of its vehicles through arctic sea ice—which is rapidly thinning and receding due to our overuse of fossil fuels.

According to West Hansen, an explorer whose planned sea kayaking expedition through the Northwest Passage will cross the path of the TCE route, the group failed to consult local residents about ice conditions. In fact, one of the putative side goals of the expedition (besides uniting people all over the world) is to provide local communities with data about ice conditions.

You read that correctly. With one pass through the area, the Trans Global Car Expedition will advise the Inuit, who have been living, traveling, and hunting in the region for thousands of years, about local conditions. The group actually issued this official statement regarding the incident: "It has also provided important data on the viability of travel on the ice in the context of global warming, which is making traveling over the ice more dangerous for Indigenous communities and other ice travelers.” One team member added, regarding the plan to recover the truck, “ . . . our respect for the land motivates our desire to do the right thing to remediate the area, and also bring the world’s eyes to one of the most pristine and beautiful places on the planet.” Is your irony meter now bouncing off the peg like mine?

The remediation, sadly, did not happen quickly. The vehicle sat on the floor of the Arctic Ocean, in the densest layer of its subsurface life zone, for five months before it was brought back to the surface, so the recovery team could take advantage of better weather and ice conditions. In the meantime the truck was rolled around on the ocean floor by currents, and wound up in water twenty feet deeper than that in which it sank. Despite this, the team claims they recovered the truck “without any damage to the fragile ecosystem.” I guess we’ll have to take their word for it, although I find it difficult to believe a 7,000-pound truck rolling around on the sea floor wouldn’t do some damage, even if there was zero leakage of fluids.

Let’s back up and think about this entire endeavor. What will the Transglobal Car Expedition accomplish, assuming they complete the trip in 2023-2024 without losing too many more vehicles to thinning arctic ice?

Both geographic poles have already been reached, multiple times, on foot, unsupported (not even any generators along . . .). How does driving internal-combustion-powered trucks to those poles expand the envelope of human endeavor? Not only is there nothing scientific to be achieved, it is in fact a prominent middle finger to climate scientists, biologists, and local communities urging preservation of these sensitive regions. (I was stunned to discover that the National Geographic Society lent its status to this project, and I wonder if the recent debacle has given the directors any second thoughts.) Will the TCE “unite people around the world” as stated on the website? Sorry, but I think Coca Cola has a better chance of doing that. (To be fair to the TCE, several so-called “eco-tourism” companies are gleefully offering cruises via giant ships to formerly inaccessible areas of the Arctic Ocean, including complete transits of the Northwest Passage.)

For just one example of the outsize impact the TCE will have on the planet, consider the single flight mentioned in the linked article. The Dassault Falcon 900 jet Russian oligarch Vasily Shakhnovsky, the apparent patron of the TCE, used to (illegally) fly to Canada to visit the team holds 3,000 gallons of JP5 jet fuel, giving it a range of 4,700 nautical miles. I’ll leave you to estimate the total amount it took to fly one man to and from Canada. (This, as well as the helicopter recovery of the Ford, also makes moot the expedition’s claim that it will use only “surface transportation.”)

Let’s back up some more. Vehicle travel—whether for personal enjoyment or ambitious, hugely financed “first-time-ever” goals—can be considered a single very large, graduated gray area. At the pale end of the scale we wouldn’t drive anywhere. But most of us reading this live in the real world, and realize that retiring to live in a cave, as the more dullard anti-environmentalists like to urge environmentalists to do, won’t solve anything. Individual and small-group travel by vehicle, as anyone who has done it knows, actually is one very effective way to genuinely “unite the world.” Thus we accept a status somewhat farther along the gray scale.

But a massive “expedition” pursuing a spurious “first” and attempting to justify it with an even more spurious scientific or “world peace” agenda lies, if you’ll forgive me, at the polar opposite end of that scale, in a very, very dark region.

Edit: After I posted a link to this story on Facebook, I received a polite and measured reply from Andrew Comrie-Picard, one of the TCE team members who was on the recovery effort for the Ford pickup. He went to lengths to assure me that the team did in fact take every precaution to minimize damage to the ecosystem, and said that fluid leakage from the vehicle had been minimal. I appreciate his information, although it does not change my opinion regarding the irony of the accident, or the massive overall impact and resource consumption of this effort, for a dubious goal.

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.