Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

Tools 101, part 1

I’ve been teaching a tool-selection class now for several years at the Overland Expo, and while most who attend are grounded in the basics of what tools are what and what they do, an increasing number of people are not. This is an inevitable consequence of the direction in which the world is headed—more and more complexity in our vehicles, fewer opportuities for shade-tree mechanics, more two-income families with simply no time to ‘mess around’ with cars. As well, vehicles have become more and more reliable and their drivetrains more durable in the last few decades. No one these days thinks a thing of handing down a 150,000-mile Civic or Corolla to a college student (and how many of those rack up another 100,000 miles before starting a new career crowned with a glowing Domino's Pizza sign?). One result of all this is the 20-something man who approached me after one class and admitted that, regarding my discussion of ratchet and socket sets, he had no idea how a ratchet and socket set worked. So I thought it a good time to step back and review some basics.

Those of us who venture off the beaten track, away from AAA and perhaps even out of cell-phone range, must assume more self-sufficiency than our pavement-bound friends. There are dozens of things that can go wrong on an overland vehicle, and fixing any of them, from easy repairs such as a broken fan or serpentine belt, a split radiator hose, or dirty battery terminals—even just tightening bolts on a roof rack—up to major events such as replacing a broken CV joint or birfield, is going to require tools.

I stress to my class attendees who plan to travel that even if they have no mechanical ability whatsoever, it’s still important to carry a set of tools. You’ll make a lot of points with any good Samaritan who stops to help if he doesn’t have to dig out his tools to use on your vehicle. And if the choice is between an attempt at a repair, or walking out, it’s surprising how many total mechanical rookies have successfully muddled through quite elaborate procedures using nothing but common sense.

The next thing I stress is that your tools should be quality products from reliable manufacturers. Think about it: If you’ve brought out the tools something has already gone wrong—why risk making the situation infinitely worse by using a poor-quality tool that breaks? With that said, few of us can afford to spend thousands of dollars on a complete outfit from Snap-on (the Rolls Royce of tool makers). So the smart strategy is to prioritize where you spend. If a screwdriver tip snaps, you can usually make do with a substitute. If the 19mm socket you’re using to remove transmission bolts breaks, you are not going to get those bolts off with your Leatherman. So let’s look at some of the elements of a basic tool kit, and their functions, starting with the most critical, and therefore the one on which you should spend the most.

Ratchet and sockets

Virtually all the important breakable bits on your vehicle—as well as many that simply need regular maintenance—are held on by either bolts or nuts. The only two proper ways to remove and install bolts and nuts without damaging them are with a ratchet and socket, or a wrench (not pliers!).

The socket part of the ratchet/socket team is a precisely sized piece that fits snugly over the bolt head or nut. Sockets come in metric sizes (10mm, 12mm, etc.) or SAE (Society of Automotive Engineers) sizes (3/8”, 1/2”, etc.) that correspond to the diameter of the bolt or nut they fit. Most new vehicles these days are metric, but a few mix both types. Note that some metric sizes are close to SAE and vice versa—you can use a 19mm socket on a 3/4” nut, for example—but the fit might not be as tight on crossover sockets, which could result in stripping a very tight fastener. (Also, note that a 3/4" bolt will not fit in a hole tapped for a 19mm bolt—the threads are different.)

Look inside a socket and you’ll see why they are referred to as either six or 12 ‘point’.

A 12-point socket is easier to pop over the head of a nut because you don’t have to turn it as far. On the other hand, a six-point socket is a bit stronger, better able to grip a rounded-off fastener—and thus generally better for a field kit. Speaking of rounded-off fasteners: In 1965 Snap-on patented a system they called Flank Drive. By radiusing the apex of each angle in the socket, they enabled it to bear on the flats of the fastener, rather than the corners. This allowed more torque to be applied, and also made it easier to remove butchered fasteners. Once the patent ran out, many other companies copied the system, giving it their own names since Snap-on still has the Flank Drive trademark.

Note the radiused points on the Flank Drive socket, left.

On the other, drive side of the socket is a square hole, and this is where the socket snaps on to the ratchet. The ratchet has a toothed mechanism in its head that allows it to lock when turning in one direction, while ‘ratcheting’ freely the other way. Thus tightening or loosening a fastener can be accomplished with a convenient back and forth movement of the ratchet handle, without the need to lift the socket off the fastener and reposition it. A lever or dial reverses the direction of ratcheting.

The square peg on the ratchet, on which the socket fits, is called the anvil or square drive, and its diameter determines the size of the ratchet: A 1/4” ratchet has a 1/4-inch diameter drive, and all sockets for that ratchet will have 1/4-inch diameter drive holes (that’s why you’ll see confusing references to, for example, a 3/8” socket for a 1/4” ratchet). A 1/4” ratchet is suitable for light-duty fasteners. A 3/8” ratchet is perfect for most general automotive work, and should be the first set you buy. A 1/2” ratchet is what you’ll need for more heavy-duty jobs. In terms of the range of fasteners each will handle, there is much overlap, but in general I think of my 1/4” ratchet set as suitable for anything from 4mm up to 12mm fasteners; the 3/8” works well for anything from 8mm up to 19mm, and the 1/2” set is great for 14mm on up. I rarely bother carrying a 1/4" socket set in our vehicles; the two larger sizes suffice for everything.

Left to right, a 1/4", 3/8", and 1/2" ratchet.

The number of teeth in the ratchet head has a bearing on how well it works. Hold the anvil between your fingers and turn the handle while counting the number of clicks it makes rotating 360 degrees. Thirty six clicks equals a 36-tooth ratchet, etc. Years ago most ratchets had 24 or 36 teeth, but lately the count has been going up, and today many ratchets have 72 teeth, and some now boast 80 or more. Why does this matter? Aside from a nicer feel, a finer tooth count means fewer degrees of swing before the ratchet clicks to the next tooth; this can be critical in tight spaces when you have little or no room to swing the handle. On one field repair I had a couple of years ago, my 80-tooth ratchet had exactly one click of free movement to remove a vital but nearly inaccessible nut. It took me 15 minutes to get that nut off, one click at a time—but I got it off. One caveat: It’s easy to make a coarse, 36-tooth ratchet strong, but when you get up around 80 teeth it takes better engineering to ensure adequate strength and resistance to skipping and ‘self-reversing’. So quality becomes even more important.

Materials: It used to be that ‘forged’ and ‘chrome vanadium’ or ‘chrome molybdenum’ were pretty reliable signs of a quality ratchet set. Unfortunately even the cheapest offshore brands now forge tools from chrome vanadium or chromoly, so that’s not on its own a reliable standard. You can easily forge a poor tool from chrome vanadium steel—the difference in a good tool will stem from the purity and mix in the alloy, the heat treating, the finish, and the precision of the fit on the fastener. The best way to ensure quality is to stick with a reputable brand (see below); but other features will help you identify a good set.

What should you look for in a 3/8” ratchet set? Start with the basics. The set should include:

- Ratchet

- Two extensions, one short, one long

- Standard-depth sockets from around 8mm to 19mm (or 1/4” to 3/4”)

- If possible, deep sockets from around 10mm to 19mm (These can be purchased separately if necessary. Deep sockets are used when a bolt protrudes far enough from the nut that it bottoms out on a standard socket.)

- Universal joint (to help access partially blocked fasteners)

- A sliding T-handle is nice. It’s a backup in case your ratchet breaks, and sometimes can access places where the bulkier ratchet head won’t fit.

- Some sets will include a pair of spark plug sockets, but these can easily be added later.

- In a 1/2” ratchet/socket set, look for standard sockets from about 12mm up to at least 25mm (32mm would be better). I don’t worry about deep sockets in a 1/2” set; I’ve rarely if ever needed them. For your 1/2” set you’ll also want a breaker bar for extra leverage on big drivetrain fasteners. Most breaker bars eschew a ratchet mechanism to retain ultimate strength—once the fastener is loosenedyou can switch to your standard ratchet. An 18-inch long breaker is sufficient for almost all tasks.

A superbly comprehensive and compact socket set from Britool, including standard and deep SAE and metric sockets, a sliding T handle, extensions, a universal joint (lower left), plus screw, torx, and hex fittings with an adapter. Sadly no longer made; the newer Britool products have diminished in quality.

In addition, many possible extra features are nice to look for, although it’s unlikely you’ll find all of them in one set.

- Knurled extension. This grippy area helps you to spin on (or off) a fastener before you need the torque suppled by the ratchet.

- Wobble-tip extension. A slightly rounded tip on an extension allows the socket to work at a slight angle, if an obstruction prevents you getting the ratchet directly over the fastener.

- Hex fitting. A few extensions come with a hexagonal section near the top, which allows you to apply a wrench to turn it if you cannot get ratchet on it, or if the ratchet breaks. (The more alternative and backup ways you have to accomplish a field repair, the better.)

A ratchet extension with a knurled section and a hex fitting for wrench.

A standard (left) versus wobble-tip extension.

- Some ratchets come with rubber or plastic ‘comfort handles’. These are definitely more comfortable, and prevent scratching if the handle bangs into sheet metal or paint; however, they’re also more difficult to keep clean. Fully polished ratchet handles are much better in that regard. It’s pretty much personal preference.

- A quick-release button is handy for removing sockets from the ratchet—otherwise the spring detent ball that holds the socket on can require a strong tug to overcome.

- Personally I like to retain the blow-molded plastic case that many socket sets come in. While it adds more bulk to the tool kit than if you simply dumped everything in a bag, the case keeps everything organized and easy to locate, it reduces wear on the tools, and—above all for me—it makes it easy to see if you’ve left out any sockets or other items when you’ve finished the work.

- You’ll see so-called ‘pass-through’ socket sets that eliminate the need for deep sockets. I’ve found these to be less than desirable because the components are very large in diameter and don’t work well in confined spaces. Also, they’re incompatible with standard sockets, so if you break one you can’t easily borrow a replacement or find one in some backwoods hardware store.

So what about brands? As I mentioned, the socket set is the most critical component of your tool kit in terms of quality, so if you’re going to splurge and shop at snapon.com or mactools.com, now’s the time to do it. Just make sure your payments are current on the Amex Platinum. (You can also do as I do and haunt eBay for used sets.)

Setting aside the gold standards, I’m very partial to the Facom (pronounced “fahcomb”) brand. Described as ‘France’s Snap-on’, most of their tools are now produced in Taiwan, but the quality control seems exceptional. Bahco makes some very nice boxed sets, although they rarely seem to include deep sockets.

A high-quality Facom 1/2" set with a comprehensive assortment of sockets.

SK tools makes most if not all their sets in the U.S. After a decided dip in quality before a reorganization, it seems to be back again. The finish is really good, although the ratchet I tried only had a 40-tooth head—interesting how clunky that formerly standard count feels after getting spoiled with 80-tooth heads.

Stepping down a notch, but still functional, is the Sears Craftsman Professional line—as distinguished from the standard Craftsman line, which has lost quality over the last few years with a switch to offshore production. Stick with sets that include the fully polished ratchets and you’ll be okay. The thin-profile ratchets are nice, and they have 60-tooth heads.

Home Depot’s Husky line is not bad, although their ratchet design is an annoyingly blatant ripoff of the Snap-on style. But the prices are excellent and the tools have a lifetime guarantee (which, remember, is great but of little immediate value if the tool breaks in the field). Lowe’s Kobalt brand seems well-made, and the stores I've been in carry a wide selection. They make a 40-piece SAE and metric 3/8” set with a 72-tooth ratchet that is a bargain at around $30, although, again, there’s that Snap-on-esque handle (insert eye roll).

Once you've got a 3/8" and 1/2" socket set, you'll be ready for the companion tools for removing and attaching fasteners: Wrenches.

All you need for good camp coffee

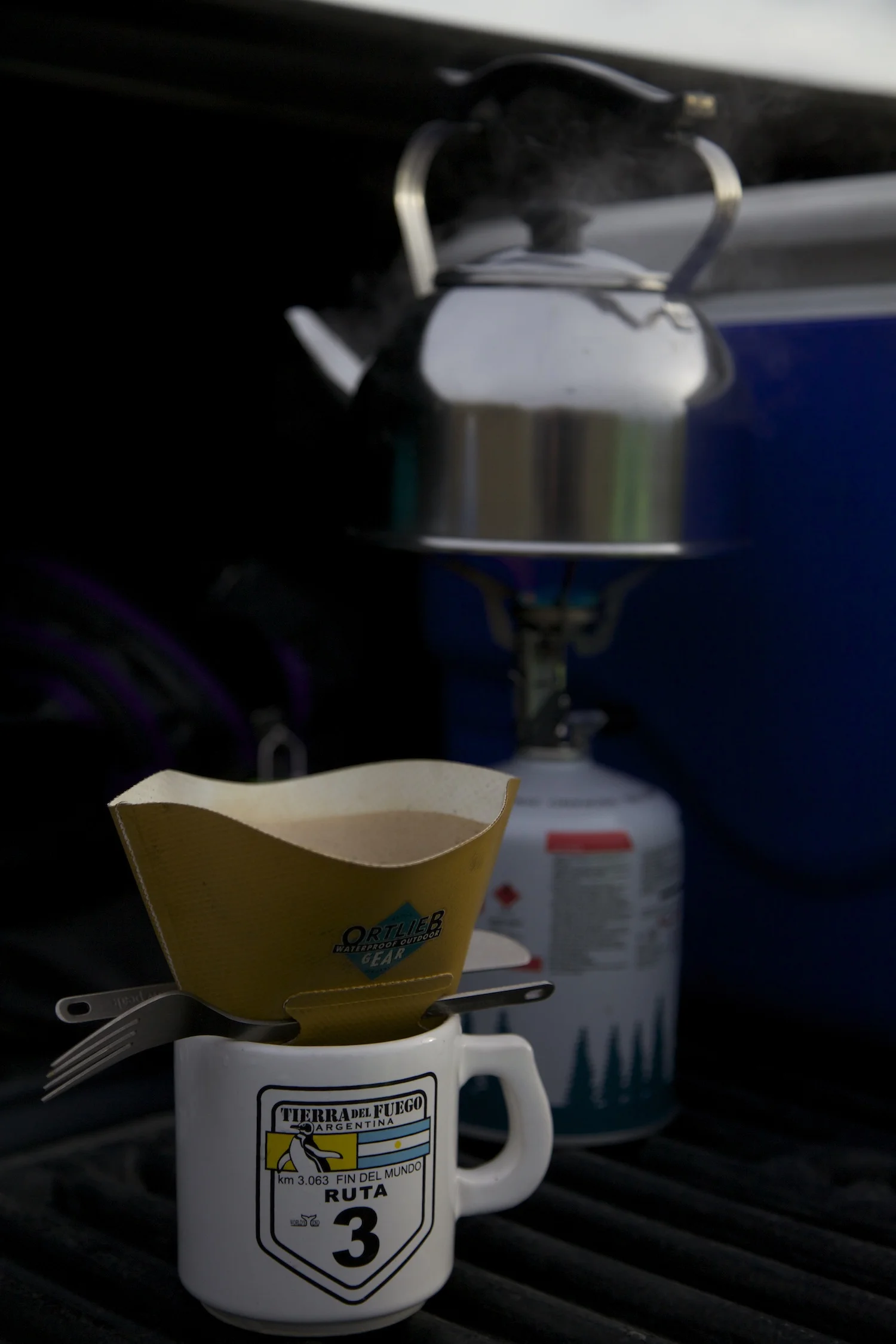

Snow Peak Giga Power stove, MSR Titan kettle, Snow Peak 450 mug, Ortlieb filter holder

Of all the challenges facing overland travelers, none results in more angst or 50-page forum threads than the problem of how to make a good cup of coffee when you’re on the road. Vehicle breakdowns, border crossings, terrorism, ebola—all pale as insignificant in comparison to that moment when you must crawl out of a warm sleeping bag and jump-start your metabolism.

In this respect, tea drinkers have it easy: Drop a PG Tips bag in a cup, add boiling water, and Bob’s your uncle. Of course, we coffee drinkers might hint that the effort involved is a clue to the worth of the resulting beverage. To which the tea drinker replies archly, “Tea built the British Empire!” To which we reply slyly, “What empire?” And so on . . .

Where was I? Right. As a reformed coffee Neanderthal (30 years ago my ‘coffee’ was powdered General Foods Suisse Mocha—which, to be . . . generous, was easy to make while camping), my first attempt at making quality coffee in the field was simplicity (and economy) itself: a #2 Mellita-style paper filter and holder suspended over a cup, filled with good fresh gound coffee, and poured over with (near!) boiling water. It was quick, waste-free, and with the innocuous grounds dumped on nearby plants, the used filter took up zero room in the trash, or could be burned on that night’s fire. Cleanup was a few tablespoons of leftover hot water to rinse the cup. It was a perfect system for the needs of a camper, even when traveling by motorcycle.

However. The very simplicity of the system made me vaguely uncomfortable as a born-again coffee snob. Sure, it seemed to taste as good as anything I had elsewhere, but was it just the setting that made it seem so? Was I somehow cheating in the elite club I’d joined?

Thus began a rather prolonged binge of consumerism during which I tested every sophisticated coffee-making apparatus on the market: mocha pots, French presses, double-wall French presses, double-wall-double-filter French presses, 12-volt drip makers, the ‘Soft Brew’—a beautiful ceramic thing with a stainless microfilter—the Aeropress, and others I’ve forgotten.

All made fine coffee. A couple even made coffee I convinced myself might be incrementally richer than my original system, although my opinion might have been subconsciously swayed by how much I’d spent on each device. The AeroPress was excellent and lasted longer than most others. But after a while I realized that every single one I tried shared two significant disadvantages for camping: They were bulky, and they were complex and thus took an inordinate—sometimes scandalous—amount of precious water to clean. In Jellystone Park with a spigot at each campsite the latter wasn’t an issue, but in the field with 20 gallons of water (in the Four Wheel Camper) or two (on the motorcycle), losing a pint or more every morning hurt.

It was about the time Roseann stood in front of an open kitchen cabinet and said, “Do you know how many coffee makers are in here?” that I realized I’d been missing the obvious. What I needed was a system that made good coffee, and was also compact and didn’t take a lot of water to clean. In other words—you guessed it—I needed a #2 Melitta-style paper filter and a filter holder, and some good fresh-ground coffee.

So I’m here to say that the ultimate camp coffee maker is also the simplest, and the cheapest—unless you’re a motorcyclist or bicyclist and spring for some titanium bits. Here’s what I use; this list is easy to modify to go lightweight ($$) for bicycling or motorcycling, or weight-be-damned (¢) for four-wheeled travel.

Kettle: MSR Titan. The titanium Titan ($50) is one of those rare pieces of equipment I’ve used over the years that is simply above criticism. At 4.2 ounces it adds little to the baggage. Its .8-liter capacity is perfect for one person. The Titan is as wide as it is tall, making it stable on a micro-stove. Stay-cool handles and lid lifter make it easy to manage. It serves equally well as a kettle, cook pot, bowl, or mug if you’re on a tight weight budget. And a standard isopro fuel canister drops neatly inside, along with several models of foldable microstove. Of course if you’re traveling in a truck any cheap stainless kettle will do—we picked one up in Ushuaia for under $15 for a trip through South America.

Mug: Snow Peak 450 double-wall titanium ($50). The 450 holds a proper cup of coffee (14 ounces worth) and keeps it hot for ages. In fact the only downside to this mug is that it’s essentially worthless as a handwarmer—the thing just does not conduct heat. You could shave off a couple of its 4.2 ounces (as well as 20 bucks) by going to the single-wall version, but the insulated one gives you better excuses to put off packing up on a lovely morning. Driving a Land Cruiser and don’t need a $50 coffee cup? Any Tacky Tourist Mug will suffice.

Stove: There are a lot of really good canister microstoves on the market for motorcyclists. I still like my Snow Peak GigaPower, but their newer LiteMax is excellent as well. Alternatives include the MSR Superfly (and of course MSR’s legendary liquid-fuel stoves), the Primus Express, and the Optimus Crux. Any of these will fit inside the Titan pot on top of a canister. For the Land Rover? Take your pick of larger canister or propane stoves. The Partner Steel stoves are superb, stable, expensive, and indestructible. A smaller option is thesuperb, stable, expensive, and indestructible single-burner Snow Peak Baja Burner. And for those who are rolling their eyes and thinking ‘gear snob,’ I carry in my FJ40 a 10-year-old single-burner propane stove from Stansport that cost all of $12.50 at the time ($25 now), and works just fine.

Holder: Ortlieb filter holder ($12). Made from the same indestructible material as the German company’s indestructible luggage, this filter holder folds flat, takes up zero room, and weighs a scant ounce. You prop it over your cup using anything handy—twigs if need be, your Snow Peak titanium utensils if you got ‘em. Mine came with only one exit hole and was glacially slow, so I snipped an extra hole in the other corner, which worked perfectly. The Ortlieb holder works just as well in a truck kitchen as on a bike, but the standard plastic Mellita filter holder works even better, and costs about three bucks at a hardware store.

Coffee? Well, see here—or, if that's a bit much and you cannot access locally roasted beans, most grocery stores carry Peet’s Coffee Major Dickason’s Blend, which is excellent. And for those who, like me, adulterate their coffee with half and half, I give you the Mini Moo. Single-serving size, no refrigeration needed.

Tacky tourist mug, $15 kettle

Update on crappy tents

When the article below was shared on Facebook, I got a lot of comments. Many were in complete agreement, and related the writer's own experience with either good or bad gear. But there were several diatribes from those who accused me of being elitist—despite the fact that I listed several companies that make decent tents for under $200—and an extraordinary claim or two about cheap tents performing beyond what I would consider, er, likely, such as standing up to hurricane-force winds. Obviously it would be impossible for me to either prove or disprove such a thing; however, in counterpoint I give you this photo, which I took on the coast of the Sea of Cortez some years ago, when Roseann and I were instructors at the Audubon Institute of Coastal Ecology.

Note the sea state and lack of surf or whitecaps. The breeze was blowing at what I estimate was no more than 25mph, yet this motley batch of department store tents was clearly in dire straits. If I recall correctly, at least three of them wound up completely trashed with broken poles and torn fabric, despite attempts to guy them out and stake them properly. Several others were simply uninhabitable. Note, however, the green Timberline tent on the far right, and, in the far rear, the white Sierra Designs dome—a good sized one—each of which shrugged off the wind with zero drama.

I'll say it again: It's stupid to economize on your tent.

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.