Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

Parabolic springs: What exactly are they?

ARB/Old Man Emu recently announced, with great fanfare, a rear suspension kit for the 70-Series Land Cruisers that includes a two-leaf parabolic spring for each side, plus adjustable air bags to compensate for overload conditions. It can replace a standard semi-eliptic spring pack that might require 12 or more leaves to support an equivalent load.

Other manufacturers, such as Terrain Tamer, have also introduced parabolic springs kits for 70-Series Land Cruisers, as well as Series II and III Land Rovers.

But what exactly is a parabolic spring? And is it really better than a standard leaf spring?

The individual leaves of a standard, semi-eliptic, multi-leaf spring pack are stamped and then bent from strips of heat-treated, medium- to high-carbon steel, more or less rectangular in cross section, and of consistent thickness and width the length of the leaf (except for, in some cases, when the ends are rounded or have the corners relieved). When attached to a simple pivot at one end, with the other free to rotate a movable shackle, a single leaf resists bending in a fairly uniform fashion throughout its travel. To increase strength—that is, load-carrying ability—and add progressive resistance, progressively shorter leaves are added beneath the top leaf, held loosely in place with floating brackets that do not restrict movement. As the spring pack is compressed, each leaf slides against the adjacent leaves. This inter-leaf friction results in a self-dampening effect—unlike, for example, a coil spring, which has little internal resistance and relies almost entirely on a shock absorber (damper) to control oscillations.

However, that inter-leaf friction also degrades the ride quality of a leaf spring as well as its compliance—the ability to compress or extend fully. And this effect worsens as the spring gets dirty and/or rusty. Some manufacturers (such as OME) install replaceable anti-friction pads at the leaf tips, which help noticeably but do not eliminate the problem.

Years ago a few manufacturers—among them Nissan—attempted to create a progressive-rate leaf spring by making the leaves thicker in the middle, tapering in a linear fashion to the tips, as in the (very) simple schematic below. This involved a relatively easy manufacturing process. However, these “taper-leaf” springs proved less than ideal as bending stresses were not evenly distributed through the length of the leaf, resulting in weak points and failures.

Enter the parabolic spring.

While it’s difficult to discern looking at it from the side, the thickness taper of a parabolic spring follows a complex mathematical formula. Rather than simply tapering straight from the center of the leaf to the end, a parabolic spring looks like an extremely stretched-out version of the illustration below. As you might imagine, it’s significantly more difficult—i.e. expensive—to design and manufacture than simply stamping out flat lengths of steel and piling up enough of them to support a load.

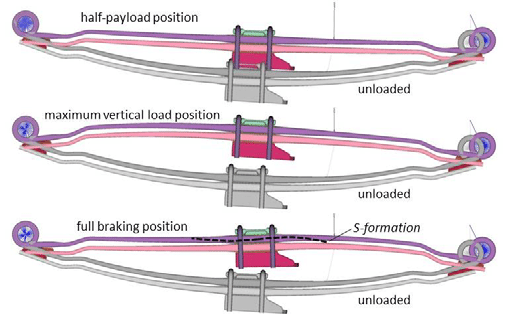

The results, however, are worth it. Not only is a parabolic leaf progressive in its operation, it is also nearly as compliant as a coil spring due to the lack of internal friction and stress. Theoretically a single parabolic leaf would be sufficient to function as a spring; however, due to the ramifications if the leaf did break, most parabolic spring kits for vehicles comprise at least two leaves, and the lower leaf will have a full military wrap on each eye, to contain the upper spring should it break. These leaves touch only at the spring seat in the middle, and at the ends, so there is virtually no interleaf friction. Most kits also include a free-floating overload leaf that only engages under high load or compression. The illustrations below are from a (densely technical) Researchgate-published paper on leaf spring design, available to read or download here.

There’s more: A parabolic spring equivalent in load-carrying capacity to a standard multi-leaf spring weighs at least 30 percent less, drastically reducing unsprung weight and further improving ride and handling. Convert an all-leaf-sprung vehicle to parabolics and you could take 80 pounds off its total mass.

The conversion job is straightforward, no more complex than changing out standard springs, although the vehicle will almost certainly require new, firmer shocks to compensate for the loss of inter-leaf friction. Series Land Rover owners I know who’ve converted describe it as “transformative.” This diagram shows the magnitude of travel possible with a parabolic spring system, as well as the longitudinal “S” deformation any leaf spring undergoes during severe braking.

While it’s easy to find parabolic spring kits for Series Land Rovers and the 70-Series Land Cruisers, diligent searching revealed no such kits for my FJ40, although I heard that one company did offer them for a while years ago. Damn. (Edit: See later articles for much better news!)

Incidentally, there is no relation between the terms “semi-elliptic” and “parabolic” in leaf spring terms. Semi-elliptic refers to the shape the entire spring pack assumes from the side; if one were to draw this shape out into a connected oval, it would be roughly elliptical. A parabolic vehicle spring pack assumes this same profile and is thus also semi-elliptical.

Ineos Grenadier Quartermaster announced for the U.S.

In a not-too-surprising move, Ineos has announced that its dual-cab pickup version of the Grenadier, the Quartermaster, will be imported to the U.S.* I waited a week before writing this, trying to find figures on wheelbase, but I haven’t yet been successful. It appears to have virtually the same wheelbase as the SUV version, but with a significantly longer rear overhang. If true, this will obviously reduce the Quartermaster’s departure angle while not affecting its breakover angle.

Surprisingly, cargo capacity remains virtually identical at a reasonable but not outstanding 1,675 pounds.

Bed dimensions are reportedly designed to fit a standard European pallet, which is meaningless to U.S. overlanders. Dimensionally it’s 61.6 inches long and 63.7 inches wide. Not many of us will be sleeping in the bed with the tailgate up. And there’s the matter of the spare tire, taking up a considerable amount of interior room, as it did in the original Range Rover. Notwithstanding the Quartermaster’s fine stock rear bumper, I’m sure the aftermarket will produce a swing-away carrier soon after the truck is introduced in 2024.

Despite the short bed, with an Alu-Cab-style clamshell camper one could build up a very livable, if compact, interior, or perhaps install a lightweight Four wheel Camper with an interior such as this one on a Jeep Gladiator. Of course you’d be flirting with the GVWR limit quite soon.

More details and thoughts as I learn and come up with them . . .

*The Ineos Grenadier SUV is built in France. Logically the pickup would be too, but if so Ineos would run head-on into the U.S. 25-percent tax on imported pickups, which the Japanese have been avoiding for decades by building their trucks here. Time will tell how the company will handle the issue, although Sir James Ratcliffe has enough cash to do some very heavy lobbying in the U.S. to have that silly bit of legislation—enacted purely for the profit of domestic truck makers—rescinded.

More on the 2024 Tacoma

With very, very few exceptions, the more I learn about the 2024 Tacoma, the more impressed I am by what Toyota has done to transform their number-one-selling mid-size pickup. Here are some updates to my previous post.

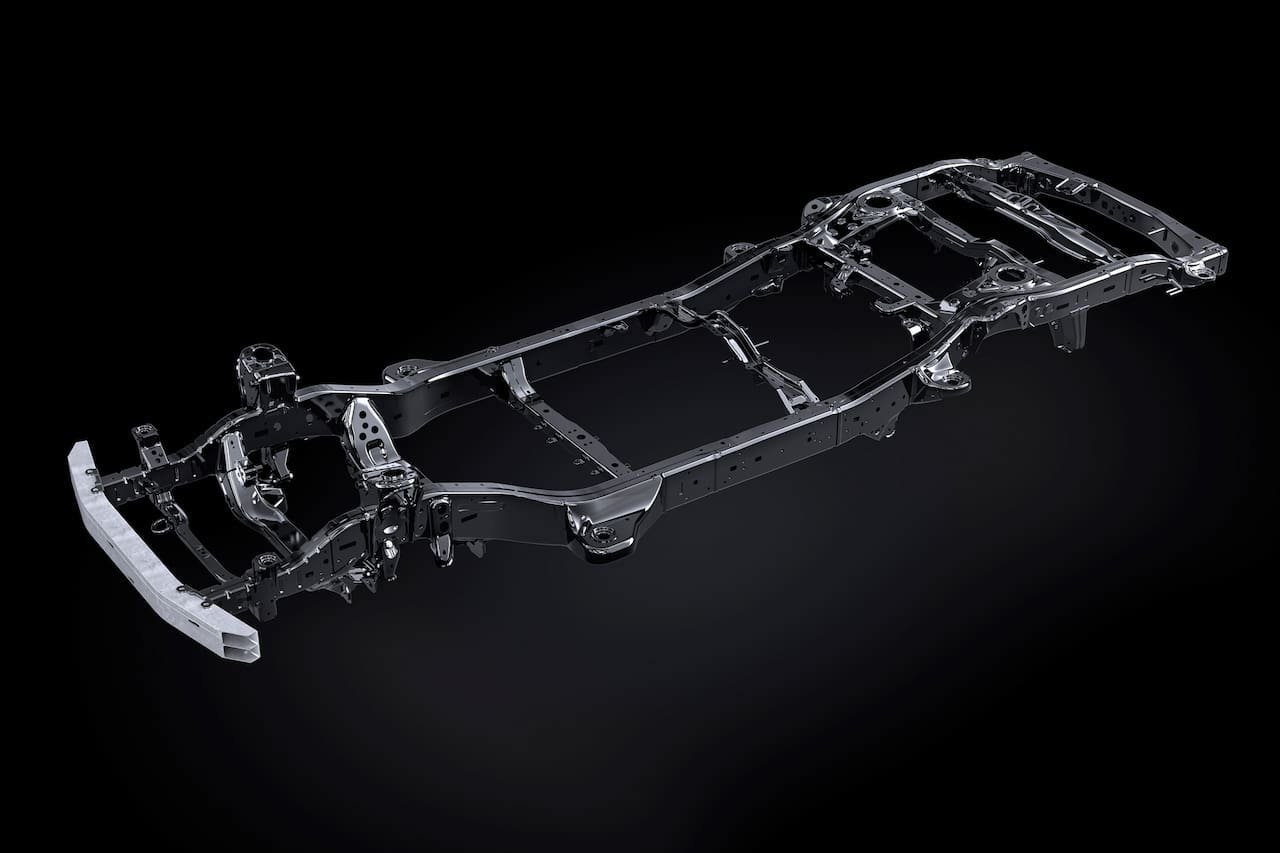

The Trailhunter model is by design set to be the go-to model for overland travelers, with good reason. It has a class-leading 1,700-pound cargo capacity—for comparison, that’s almost 150 pounds more than the current RAM 2500 Power Wagon. Like all the new Tacomas, the Trailhunter’s TNGA-F chassis is not only fully boxed, but reinforced at stress points with laser-welded gussets. All-coil suspension and OME shocks (not, however, as has been rumored, BP51s) should maintain excellent ride and handling when loaded. The tires are 33 inches in diameter, and the hybrid powertrain option, with its stupendous 465 lb.ft. of torque at 1,700 rpm, boasts a rear differential with a 9.5-inch ring gear, equivalent to that in the Land Cruiser. That is one beefy third member.

Add up the other features, whether standard or optional: steel ARB rear bumper with rated recovery points, available built-in air compressor, Rigid Industries auxiliary lighting, disconnectible front anti-roll bar, a locking rear diff, raised air intake, a 2,400-watt AC inverter on the hybrid i-Force MAX, and you’ve got the Tacoma we’ve been dreaming of.

Disappointments? One major one: There is no Access Cab available, only a crew cab with either a five or six-foot bed. But if you choose the six-foot bed you’ll be buying a “mid-size” truck with a wheelbase of 144 inches. That’s one inch less than the Tundra. Given the company’s obvious research into the overland market, I’m surprised at the lack of an Access Cab model with a six-foot-plus bed, for the many travelers who sleep back there.

Okay, two major disappointments: The hood scoop is still fake. Sigh . . .

As I mentioned, these hardly detract from the giant leap for mankind represented by the new Tacoma. There’s always the possibility that the company will add back the Access Cab option, although I’d bet it was solid data from sales numbers that made them decide to delete it in the first place. How many third-generation Access Cab Tacomas do you see driving around, compared to crew cabs? Not many.

Vintage Dodge Power Wagon camper

Full disclosure: I lifted this maddeningly fractional story off the Maple Leaf Up site, a forum for fans of Canadian military history and equipment. I was looking for ads for or images of early Power Wagons, as part of a review I’m writing for Wheels Afield on a new RAM Power Wagon.

On a page of various PW images I found this. Just the one page of an obviously longer piece, describing in part a fabulous camper built by S. Robert Russell and “his wife,” on a used Power Wagon they bought from a Miami car lot. Look at the features and you’ll see it would stand side by side with the most full-featured of its kind today. The article identifies the truck as “front-wheel drive,” which is clearly a mistake by the writer.

I Googled S. Robert Russell, and “S. Robert Russell Power Wagon,” but found nothing. If anyone else tries and finds the bottom of the rabbit hole, let me know!

Seemed like a good idea . . .

Mount a massive (5,000 pound dry weight) overhead camper with an eleven-foot-long floor and multiple slide-outs on a short-bed truck. Then hang a motorcycle off the back.

The owners claim Ram should be responsible for the very expensive repair, saying the stated load capacity of the 3500 truck is 7,680 pounds. It appears, first, that they specced the wrong truck, looking up a regular-cab, long-bed 2wd 3500 model. The capacity of a crewcab 4x4 is significantly lower.

But that’s nearly beside the point. It doesn’t take much thinking to realize that a pickup is designed to carry its stated load in the bed, not six feet off the back. The leverage applied to this truck’s chassis must have been stunning over mediocre Baja roads. I’m on the side of the giant corporation this time.

Full story on MSN here.

Trail Turn Assist, the Rivian "Tank Turn," and other environmentally destructive tricks.

During my test of the new Ford Bronco—a vehicle I liked a lot—I tried out its Trail Turn Assist feature, as you can see demonstrated in the video above. TTA drastically shortens the turning circle of the vehicle by applying the brake to an inside wheel, essentially dragging it through the turn.

Of course, in a normal scenario you wouldn’t be initiating a 360-degree turn such as in my demonstration above, conducted in a heavily used wash and cleaned up afterwards. Its utility would be negotiating a tight maneuver when, say, a boulder threatens the outside corner of the vehicle, or a drop-off threatens the entire vehicle. However, there’s nothing to prevent an owner engaging it simply to show off how tightly he can reverse course. And no matter how briefly one engages it, it will impact the trail.

My approach to driving, or to teaching someone to drive—as with all instructors I know—is, at all times, to try to minimize or eliminate wheel spin, which causes both a loss of traction and control and results in degradation of the surface, particularly in places where multiple vehicles are likely to lose traction. And wheel spin while the vehicle is stationary does more or less precisely the same thing as a locked wheel while the vehicle is moving: It wears away at the substrate, increasing erosion.

I’m not going to claim I would never use TTA if I owned a Bronco, but I would be extremely reluctant to do so.

As potentially damaging as TTA is, it pales before the much-hyped “Tank Turn” the much-hyped Rivian electric pickup can accomplish. By powering both wheels on one side forward and both wheels on the opposite side backward, The Rivian can essentially spin in place. The resulting destruction of the trail is easy to see in the videos produced by the company itself. You can see the entire sequence here.

The Tank Turn “feature” has actually been delayed for an unknown period after the Rivian engineers recognized several issues—including the fact that when the turn is enabled, traction is completely lost. Thus if an owner were to initiate it on a slope, the vehicle would immediately begin sliding downhill.

Rivian will undoubtedly warn that the feature is only to be used on a “closed course,” just as they say for their “Drift Mode,” designed for “advanced drivers wanting to drift their R1T on a closed course.”

Wink, wink.

Sadly such hypocrisy is by no means limited to the Rivian company (see here). Every truck maker loudly proclaims adherence to Tread Lightly practices, while producing advertising material expressly promoting the exact opposite. There are certainly those consumers who are responsible enough to eschew aping the ads, but there are tens—hundreds—of thousands who are not. I see the results every single time I head out on a trail, and it has been getting exponentially worse. Blame it on what you will, but there has been an unmistakable increase in self-centered behavior on public land in the last half decade or so. More litter, more driving completely off trail, more hooning on the trail. These are not the type of people who will respond to a friendly lecture. Yet they are the ones who will scream when severely damaged trails are shut down by overworked and underfunded public lands managers.

Short of funding a sniper division in the BLM, I really don’t have a solution.

This is not your father's Land Rover Defender

(Note: A version of this article originally appeared in Wheels Afield, Spring 2021. I’ve expanded it here, and also included some comparisons to two vehicles potential buyers might also consider, the Wrangler Rubicon and the new Ford Bronco, a Badlands version of which I recently tested. Keep firmly in mind that the Defender costs around $15,000 to $20,000 more than the other two with similar spec, due in large part to its technologically more complex, aluminum-intensive unibody construction and all-independent air suspension.)

A line from my test notes reads: If you need a quick 90-mph sprint to scoot past a paint-scouring dust devil charging the highway ahead of you, the new Land Rover Defender is eager to oblige.

I’m willing to bet that’s the first time you’ve read “quick 90-mph sprint” and “Land Rover Defender” in the same sentence.

I also could have included in that sentence terms such as unibody construction, fully-independent air suspension, 14-way memory heated seats, photo-darkening windscreen, panoramic sunroof, 400-watt Meridian sound system, dual-zone climate control . . . but you get the picture. Stepping from the last iteration of the Land Rover Defender into the new one is like going straight from an Underwood typewriter to a MacBook Pro.

As a fan (and owner) of the original Defender, I was one of approximately eight aficionados worldwide who weren’t enraged at the re-invention of the world’s most famous safari vehicle. I knew it was never going to be another bolted-together oxcart an owner could rebuild—and might well have to—under a mango tree in Zambia. It couldn’t be. Times have changed, and so has Land Rover. The company tacitly ceded the expedition, NGO, and insurgent market to Toyota’s bulletproof 70-series Land Cruiser a couple of decades ago.

At the same time, they were never going to retire the name Defender like some star ball player’s jersey number—it is marketing platinum. Thus the new Defender.

And what to make of it? In the glacially extended run-up to its actual introduction, JLR (Jaguar-Land Rover) claimed the new Defender would eclipse its predecessor in comfort, handling, safety, economy, and power, while also surpassing it in off-road ability—no great feat on the first bits, but challenging indeed to simultaneously achieve the latter. In early January 2021 I finally got a 2020 Defender 110 SE all to myself for four days to prove or disprove those claims (press launches are interesting, but minutely orchestrated to show off all the strengths of a product and none of its flaws).

The first official photos of the new Defender elicited a collective “Eew!” from traditionalists. Despite JLR’s references to numerous “stirring evocations” of the original two-box design, modern aerodynamics and aesthetics have melted the shape into a generic form more likely to be mistaken for a Kia Soul than a Series II. By comparison, any Jeep or Bronco owner brought to 2021 from 1966 would instantly recognize either vehicle.

The rounded edges also have the effect of making the new four-door Defender 110 look decidedly smaller than the old one, despite the fact that it is larger in every dimension except height (and even that with the air suspension fully raised). It’s also heavier.

I got used to the unexceptional styling. I did not get used to the “Martha Stewart sample swatch,” as I called it: the strange body-color square stuck in the middle of the greenhouse. I could picture a couple agonizing over the paint choice on their new Defender. “Okay, how about this one? It’s called, um, Gondwana Stone?” (Don’t laugh—that is the actual name for the color on my test vehicle.) Some gloss black Krylon would fix the sample swatch. At least my ride didn’t sport the bizarre, optional Flintstones-lunchbox “side-mounted gear carriers,” which perform the dual function of hampering rearward vision and compromising aerodynamics.

Any sense of disappointment disappears once you slide into the driver’s seat. The new Defender has what is quite simply the most strikingly elegant dash ever put into a production vehicle. The instrument cluster in front of the driver employs all-LED instrumentation, including the “analogue” tach and speedometer—brilliantly crisp and visible in any conditions, and of course programable to display various functions and gauges. The 10-inch touch-screen in the center of the dash, nestled below an upholstered but structural magnesium beam/grab bar spanning the width of the cockpit, actually looks like it belongs there, in contrast to the stuck-on-iPad look of so many; its graphics are sharp, and function, according to my tech-savvy wife, is intuitive. A pod below houses the stubby shift lever and twin climate control/multi-function knobs. There are a few ergonomic glitches—the gear indicator on the shifter is invisible when you’re actually shifting (although there’s a duplicate next to the tach), the low-range button is oddly tiny in comparison to its importance, and identifying the button to convert one of the climate-control dials to a 4x4 drive-mode selector requires a dive into the 490-page owner’s manual. Quibbles, really—I could sit and admire this dash for hours.

By comparison, the current Wrangler dash is pleasingly robust-looking, and major dials are easily read, but it is far less elegant. The new Ford Bronco’s dash pales in comparison; it’s an awkward mix of round and square dials, although the Bronco’s traction-aid buttons are all in a row in the top center of the dash—a brilliant arrangement and more logical than the Defender’s more cryptic placement.

In back there’s comfortable seating and, more important, a completely flat, rubber-matted load bay with the rear seats folded, perfectly rectangular. Owners under five-ten or so will find it comfortable to sleep side by side as a couple, or solo (diagonally) if you’re taller.

Going back to the Wrangler and Bronco: The former suffers from speakers and other structures that intrude into the load space, especially at the back. The latter has a very usable rectangular load bay, but there is a sharp raised shelf where the back seats lie down. The Defender’s load bay wins easily on space—and load carrying as well: Thanks partly to those adjustable air springs, the Defender will carry 600 pounds more than the Wrangler Rubicon, and almost 800 more than the Bronco.

With the power seat adjusted every way to Sunday, and the tilt/telescope wheel positioned, the promised massive improvement in comfort becomes plain. “Land Rover elbow” is officially an affliction of the past. Push-button-start the 395bhp/407lb.ft. Ingenium 3.0-liter inline six, both electrically supercharged and twin-scroll turbocharged, and backed by ZF’s excellent eight-speed transmission, and it’s also clear no Defender owner will ever again be beaten from a stoplight by a furniture-delivery truck. Zero to 60 in 6.5 seconds puts it level with my old 1982 Porsche 911SC. Yet on a 300-mile mixed highway/dirt road trip we managed a bit over 21mpg on the suggested premium fuel. (Base models come with a four-cylinder 2.0-liter with a mere 300 horsepower.) It’s faster than a Bronco with the 330hp 2.7-liter V6, and way faster than a Wrangler with the 285hp 3.6-liter V6. The Defender also delivers its torque much lower in the rpm band than either, which is better for towing and trail performance.

That highway experience would have been sheer fantasy to any early Defender owner. In “Comfort” mode the all-independent, air-sprung suspension lends the ride of a—dare I say it?—Range Rover, with interior noise levels nearly as quiet. At an 80-mph cruise normal conversation is, well, normal. Passing semis in a vicious side wind elicited not a twitch in the steering wheel. Short of JLR’s own premium models it was the most comfortable on-road experience I’ve ever had in a four-wheel-drive vehicle.

The Wrangler, by comparison, exhibits a much firmer ride, looser steering, and obviously more transmitted road noise. The Bronco I reviewed, riding on the 35-inch Goodyear tires of the Sasquatch Package, also rode much more firmly, and displayed enough tire noise at freeway speeds to make conversation difficult—a disappointing revelation.

So: Full marks to Land Rover on transforming the Defender’s comfort, handling, safety, economy, and power. What about off-road performance?

The Defender is built on a new, aluminum-intensive platform called D7x. Engineered to pass something called, alarmingly, the Extreme Event Test (part of which involves driving repeatedly into a six-inch curb at high speed), it also raises the body of the Defender slightly higher that that of Land Rover’s other models. With the air suspension at its tallest setting, ground clearance below the nearly flat underbody is a full 11.5 inches. Approach and departure angles of the 110 are excellent at 38 and 40 degrees. (I much prefer a departure angle greater than the approach angle—if the front end clears you know the back will.) Breakover angle is also good at 28 degrees. These specs all compare favorably with the corresponding Wrangler (43º/37º/26º) and Bronco (44º/37º/23º), especially in departure angle, and the Defender’s wading depth of 35 inches beats them both (Wrangler, 30”, Bronco 33.5”). Additionally, put the Defender’s Terrain Response selector in Wade Mode and it raises the suspension to its maximum, locks the driveline, displays the water depth on the center screen, and, last but not least, lightly drags the brakes to dry them once you emerge. Impressive.

I dialed in another Terrain Response mode—Rock Crawl—for a day in Redington Pass east of Tucson, along the same route I’d earlier taken a Jeep Gladiator Rubicon diesel. With a 119-inch wheelbase instead of the Gladiator’s 137, the Defender didn’t kiss a single rock, and otherwise went everywhere the Gladiator had gone with its dual lockers and disconnected front anti-roll bar. (I did wish the Defender had the Jeep’s 17-inch wheels rather than the supplied 19-inchers, which reduce sidewall height and don’t allow airing down as much.) Rock Crawl mode locks the center and rear diffs; however, the front is left to make do with brake-actuated traction control, so those tires scrabbled a bit on steep climbs before grabbing. Nevertheless it was clear that the new Defender decisively eclipses the old one in this sort of terrain. The original’s admirable coil-spring compliance simply wouldn’t be able to overcome the lack of any cross-axle locking function. I should note that fuel economy dropped precipitously near to single digits for this run—not unexpected but roughly half what a Gladiator’s turbodiesel managed in the same circumstances.

The Defender has other tricks: ClearSight Ground View, which magically makes the hood disappear in dicey terrain, additional camera modes that lend close-up views of the front wheels or a bird’s-eye perspective. All-Terrain Progress Control allows the driver to dial in a walking pace and concentrate on steering rather than throttle management. And all the while the suspension and silky transmission continued to coddle us. At the end of the day Roseann and I agreed that neither of us had ever experienced a vehicle so comfortable on pavement and at the same time so capable in the backcountry.

However, I’ll state that here the Defender’s 4WD proficiency lags slightly behind its American rivals, largely due to the lack of a front locker and its 19-inch wheels. The Wrangler Rubicon reigns supreme in rough country, with the Bronco perhaps a tick behind. I’d rate the Defender at 90 percent of either of them. One could enhance this by installing the 18-inch wheels that are optional, along with slightly taller tires—but I would be very cautious not to compromise the overall brilliance of the Defender’s capabilities on and off road.

Another factor to consider for some of us is the difficulty of fitting (or finding) aftermarket accessories. Land Rover offers a winch as a factory option, but fitting one later might be nearly impossible for the near future. The last I heard, none of the major players in the 4x4 accessory market (ARB, etc.) is producing a winch bumper or recovery-capable rear bumper.

Of course the 800-pound gorilla lurking in the cargo compartment of the new Defender is the question of reliability. The legendary original was not, shall we say, legendary for this, and the new one is orders of magnitude more complex (quite literally a Macbook Pro versus an Underwood). Time will tell if the new, dedicated plant in Slovakia can exceed the quality of the venerable works in Solihull. One early YouTube saga involving a complete engine failure made a splash for some time, and others have surfaced detailing lesser issues. Only time will give us statistically valuable data.

In a way the baggage of that legendary name is unfortunate. If JLR had named this vehicle anything but Defender, it would have been greeted rapturously by Land Rover fanatics. The rest of us can greet it for what it is: a supremely accomplished 4x4 that is also comfortable for 600-mile freeway days, and capable of carrying nearly a ton of passengers and camping gear, or pulling four tons of trailer. I wouldn’t recommend trying to disassemble it under a mango tree with a hammer and a few spanners, but by every other objective measure the new Defender is a vastly better vehicle than the old one. I, for one, would own one in a heartbeat.

Can we admit the spare tire on the bonnet was a dumb idea?

I would venture to say that no single automotive feature is as widely recognized across the globe as the spare tire on the bonnet of a Land Rover.

The Rolls-Royce “Spirit of Ecstacy” winged lady is certainly in the running. Some might mention, say, the tail fins of a ’57 Chevy. But it’s certain more people have seen that spare tire in person, from the streets of London or New York to the dirt tracks of Kenya or Australia or Nepal.

But, honestly, it was a really dumb idea.

Let me hasten to say that it was much less of a dumb idea as originally configured, with the skinny 6.00 x 16 tires and 5-inch wide wheels standard on Series 1 vehicles. But the arrangement still made raising the bonnet a pain, reduced forward visibility, and presented a challenge in getting the spare off and, worse, getting a potentially muddy punctured tire and wheel back on without scratching or gouging the paint or the Birmabright itself.

Even the 6.00 tire on this Series I blocks forward vision.

With modern wheels and tires—even so modest a fitment as the 235/85 x 16 tires on our 110—near visibility is significantly hampered. Topping out on a steep climb with nothing but a BFG filling your field of vision is not fun. And lifting the bonnet is a genuine heave for anyone not stout of tricep.

Even the modest 235-section tire on our 110 is a problem.

I might also point out that, horizontal on the bonnet, the tire is much more exposed to UV degradation from sun exposure, and to heat from the engine. Finally, I’ll point out that in the event you are rear-ended in your Land Rover, the ramifications of that tire breaking free and coming back through the windshield are not pleasant.

And with wider modern tires it gets a bit ridiculous.

Advantages? Well, er . . . let’s see. It’s quicker to access and doesn’t get as dirty as a spare tucked under the rear chassis. It eliminates the “complexity” of a swingaway carrier, as on the Series Land Rovers’ primary competitor, the 40-Series Land Cruisers. And adding a swingaway carrier on a Series Land Rover is an easy way to obtain two spares for journeys fraught with tire hazards. But really the spare should have been mounted on a swingaway to begin with—perhaps with an optional second spare on the hood.

Anyway . . . it sure does look cool.

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.