Once unobtanium on U.S. Shores, these two expedition legends can now be had—for a price. Are they worth it?

By Graham Jackson

Images by Graham Jackson, Brian Slobe, and Jonathan Hanson

The images are ubiquitous, in National Geographic, in Geographical, on CNN and BBC, even on the web on Overland Expo and Exploring Overland: two of the most iconic and aspirational expedition vehicles in the world; the Land Rover Defender 110 Station Wagon and the Toyota Land Cruiser 75 Series Troop Carrier (Troopy).

Both come from the same generation, the Defender started production in 1983 (yes, I know, it wasn’t named “Defender” until 1990, but it’s the same vehicle) and the 70 Series (J7) started production in 1984. From that time they became common sights in videos and news reports from the furthest, most adventurous parts of the world. Every wildlife documentary seemed to have a 110 lurking in the background and every natural disaster video report seemed to have a 70 Series on hand. These two vehicles became legends in short order.

But for the longest time neither vehicle was available in the USA. Sure, in 1993 Land Rover imported 500 federalized Defender 110s, which now fetch staggering prices on the used market—a testament to the pent-up demand for this vehicle. Mining companies have imported 75-series Land Cruisers, but they are not road legal and spend most of their lives as workhorses underground, where the incredibly tough conditions means no other vehicle is adequate. Why neither Toyota nor Land Rover took the effort to bring the vehicles into the USA as a major model for sale to the public can only be answered by the penny-pushers and spreadsheet drones at either company.

However, examples from the golden era of these vehicles (mid-1990s) have now reached the 25-year-old mark, making them eligible for private import into the USA. The question is, are they worth it? Should you find a Defender 110SW or 75 Series Troopy and import it into the U.S.? Would either serve well as an overland or expedition vehicle here? Since I own both, I think I can offer some insight.

To be clear, I am referencing only the specific models mentioned. Obviously there are other Land Cruisers and other Defenders, and both marques have massive followings of experts who will call me out on any transgression, so let’s define what we are talking about:

In my opinion, the golden age for these vehicles was the 1990s, and the best of the best were the export models, which is what the UN and aid organizations typically got. For Defenders that means, at its base, the Rest of World (ROW) spec 110 Station Wagon with the 300tdi diesel engine and 5-speed transmission, in white. There are ROW spec pickups, 90s, 130s and 3-door 110s as well, but here we are looking at the Station Wagon, the 110SW. For the Land Cruiser, choosing a spec is even more murky; the J7 line has two model groups, five wheelbases, many body variations, and twenty-two different engines! Here we are looking at the HZJ75, the ‘heavy duty long wheelbase’ with the 1HZ inline 6 cylinder engine and manual 5-speed transmission with the enclosed or ‘troop carrier’ body—also in white. See the chart for specifics.

Analysis

Let’s get this one out of the way: They are both gorgeous. Something about the boxy appearance and the utilitarian stance; they exude confidence and capability even when parked. They are vehicles you cannot step out of and not look back at; like your ultimate crush, they command the eye. I put that solidly in the good list, because their legend is in no small part due to this. If you don’t find your eyes drawn back to the opening picture of this article, then . . . well, I’m surprised you read this far.

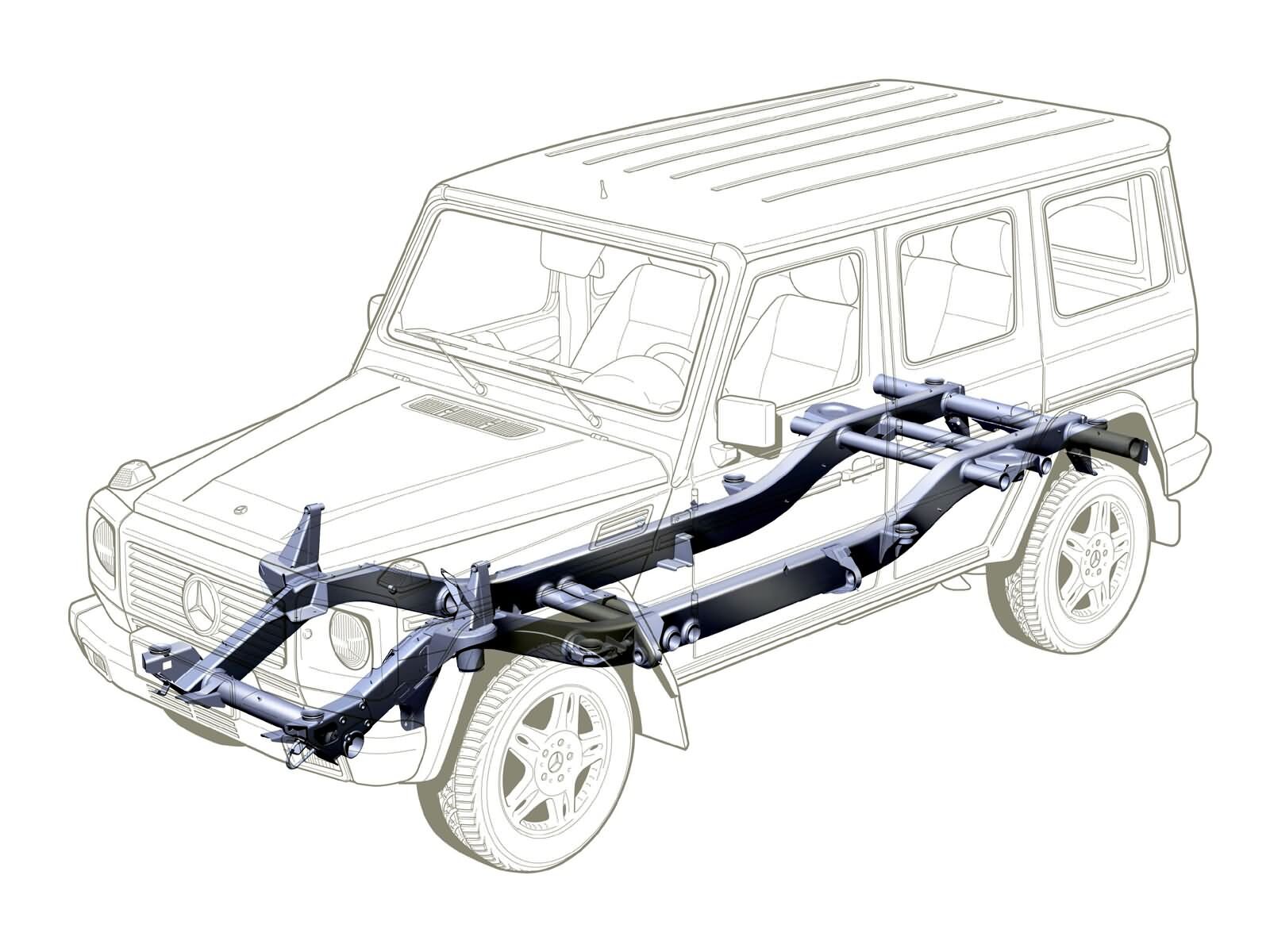

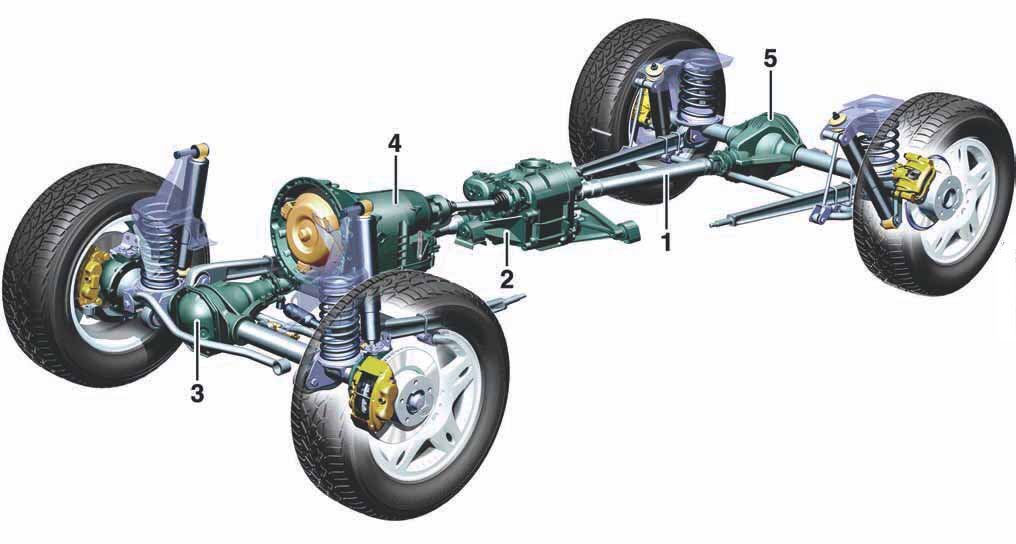

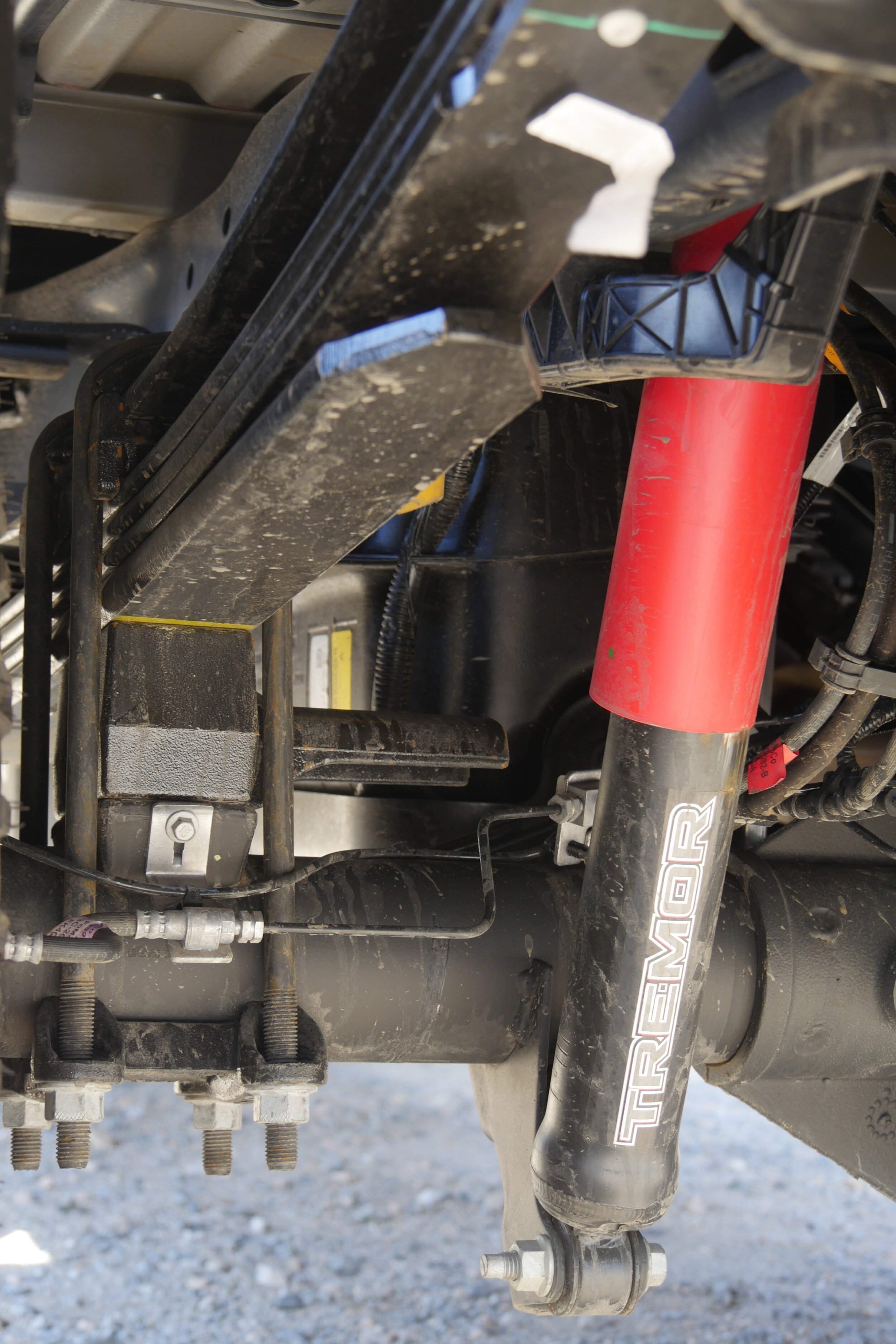

The rest of the “good” category pertains to the very utilitarian aspect that makes these vehicles excellent for expeditions and overlanding. Tom Sheppard and Jonathan Hanson have a fantastic comparison of the features in the Vehicle Dependent Expedition Guide, and I’ve included some in the chart here. Both are at the top of the range of available vehicles in terms of payload, in volume and weight, for their size. The Defender can carry a staggering 41 percent of its GVW as payload (with the heavy duty suspension installed), and the Troopy isn’t far behind at 30 percent, while the Troopy has a cavernous load bay at 87 cubic feet compared to the Defender’s at 77 (both with rear seats removed). As great load carriers, they lend themselves exceptionally well to expedition work, capable — with tried-and-true four-wheel-drive systems and suspension — of carrying the load over unforgiving terrain. The 110 has the more comfortable and compliant coil springs coupled with full-time four-wheel-drive, while the 75 has leaf springs and part-time four-wheel-drive with locking hubs—and, in many available examples, factory-optional cross-axle diff locks front and rear. The Land Rover’s fuel capacity is 21 gallons; the Troopy boasts dual tanks carrying a total of 47 gallons. Both come with five-speed transmissions.

Far from sport-utility-vehicles, these are just utility vehicles. No automatic transmissions, no driver aids like stability control or ABS—these are vehicles that have to be driven. They do not handle particularly well on the road, they lean excessively in corners when driven fast, and demand attention. But this is also an advantage. The lack of complex systems and sensors means that field repair is easier, and reliability is better. And no, I’m not going down the Land Rover reliability rabbit hole; Defenders are extremely reliable when cared for well.

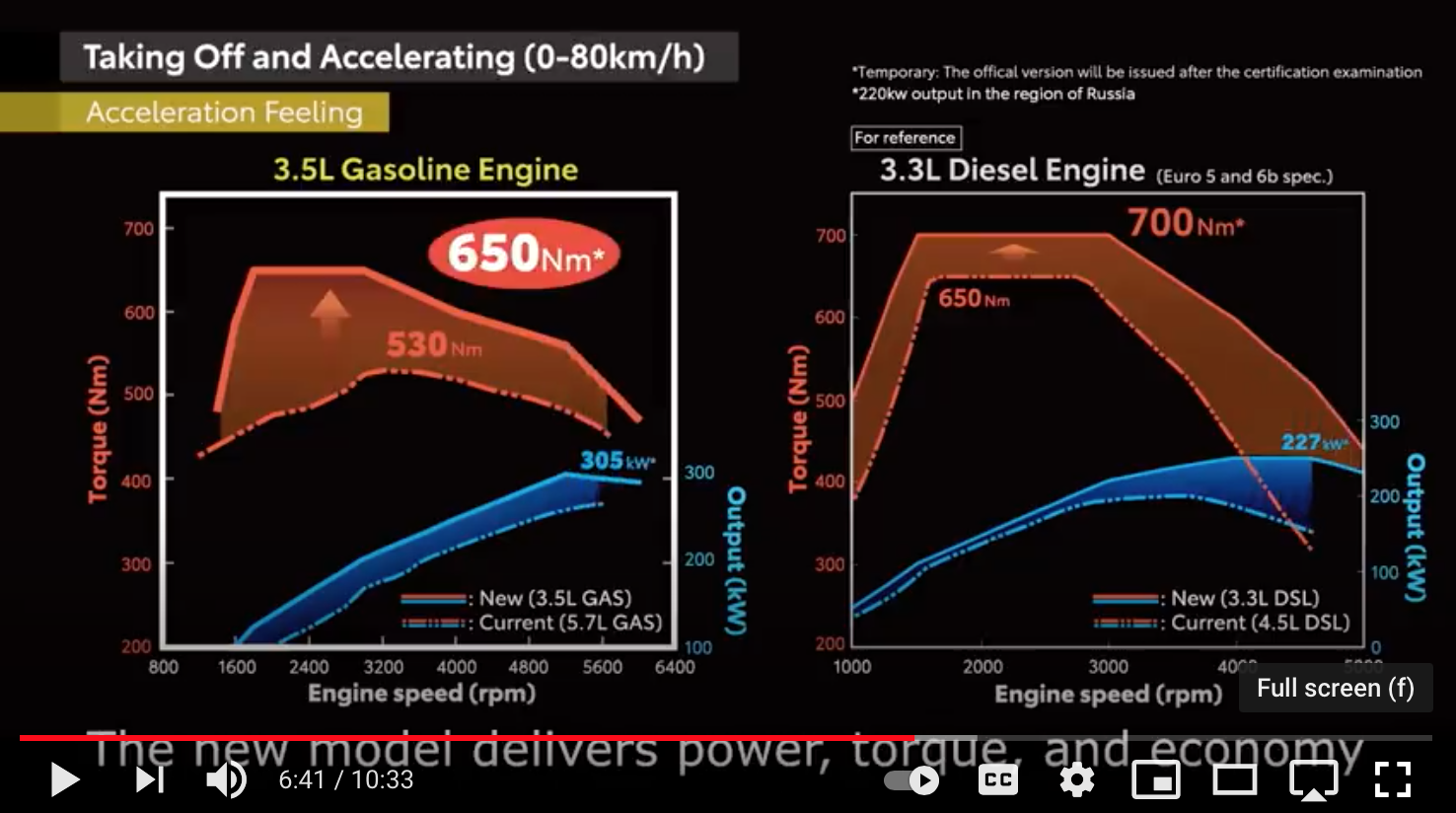

Both the 300tdi and the 1HZ are stalwart expedition diesel engines that run on mediocre quality fuel, though the 1HZ is more tolerant. Both have simple mechanical fuel injection and can run on only one wire to the fuel solenoid if required — no computers to get in the way. But that also means they are not clean engines. They will pass 1990s emission standards, but nothing better. The 300tdi is a bit cleaner since it has a turbo, while the 1HZ will serve as an extremely good black fog machine at elevation. Neither are powerful. At 111 HP for the Land Rover and 129 HP for the Toyota, they accelerate slowly and cruise the same way. We will come back to this point later.

Toyota’s ultra-durable 1HZ six-cylinder diesel has been in production for 30 years.

Land Rover’s 300tdi is exceptionally fuel-efficient.

Luxury appointments are sparse, as are electronics. No electric motors in seats, no electric windows; sound systems that are barely able to drown out the noise of the engines and the road. They are not vehicles to drive with one finger at 85 mph while sipping a latte, texting friends, and jamming to tunes. The 75 does have tilt steering and optional electronic door locks, but no remote key fob. The 110 doesn’t even have those bare luxuries. Air conditioning is the one “luxury” shared by both, though some would argue it is a necessity (and it’s only optional for the 110SW). There are no speed sensors and interlocks to stop you shifting the transfer case while on the move and no backup sensors or cameras to help those who neglected to learn how to park or use mirrors. No clutch interlock to stop you starting the engine with the clutch engaged. Again, this speaks to their utilitarian drivability which is also one of their strongest assets. These are not nanny vehicles that assert “safety;” they are vehicles that demand attention, demand driving, and reward you in that you can start in gear when bogged in soft sand, or switch to high range while on the move so long as you double de-clutch.

Stock tire sizes are the same, at 235/85R16 (760R16), one of the most common light truck sizes in the world. Pretty easy to find almost anywhere. Given the simple non-electronic mechanics on both vehicles it is very easy to get them repaired.

The load bays on both models are spacious, sparse and square. Nothing better for building out a living space or a load system for any expedition. Unhampered by plastic trim, carpeting and cup holders, they are blank slates to build up and make your own.

Both vehicles lend themselves to camper conversions.

Which leads us to the two features that makes both of these vehicles so exceptional yet have nothing to do with Toyota or Land Rover. It is the massive aftermarket support in accessories and the equally massive community of owners who are willing to help wherever you go. Because of their highly customizable and modular nature (by design), it is very simple to make a 110 or a 75 your own unique expedition rig. From pop-tops to long-range fuel tanks to water tanks and interiors, to suspensions and underbody protection, both models have excellent support in this regard. The internet is filled with fantastic examples of beautifully outfitted vehicles. This also means that it can be very challenging to find one that is unmolested or even close to stock.

But don’t mistake all my praise to imply that either vehicle is perfect out of the box. One of the reasons that they have such massive aftermarket support is that they are, by all counts, mediocre when stock. Expedition vehicles are a collection of compromises and the 110 and the 75, in stock form, are exceptional in that they are completely un-exceptional. It’s like getting the highest quality blank notebook, with the finest acid-free paper and the most beautiful leather cover, case bound, that will last forever. But it is still a blank notebook until you put a few stickers on the outside and then fill it with stories and paintings of your travels to the most remote and beautiful parts of the world.

So . . . are they good for the USA?

In a word, no, I don’t think they are.

But that speaks more to the culture and circumstances of the U.S. than it does to the vehicles. In this country most people get very little time off, and distances are so great that a good portion of any overland adventure is going to be highway time. Neither of these vehicles is good at that. With a comfortable cruising speed of not much above 65 mph, both demand patience; with solid axles and archaic steering geometry, both demand constant attention. Many, many people have purchased a Land Rover Defender after falling in love with the safari image, only to sell it when they discover it is not a modern car, lacks anything close to a creature comfort, and requires diligent maintenance. If it is expected to be a mode of travel for family vacations, strife and frustration are often the result.

With that said, if you are a person with plenty of time who is happy to cruise at 65 mph and enjoy the scenery—and to be fair, there are quite a few who can and do (looking at you Maggie McDermut)—you might live happily with either of these vehicles, and will enjoy looking back at it every time you park and get out. When modified in any of the hundreds of variations possible, up to and including pop-tops, cabinets with sink and stove, hot shower systems, awnings, and more, once in camp they are the equal of any more “modern” vehicle.

Cabinetry turned this Troopy into a mini motor home.

Finally, of course, if you ever do have the opportunity to ship your Defender or Troopy overseas to Africa, Australia, or South America, you will be driving one of the premier choices for extended exploration in the remotest regions of the planet. It will be a notebook in which you can write your own adventures. If such a vision inspires you, I cannot recommend either of these vehicles highly enough.

Graham Jackson is the long-time Director of Training for the Overland Expo, and a founder of 7P Overland, a professional four-wheel-drive training and equipment-supply organization. Their website is here.