Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

The hazards of touch-screen ubiquity

Have you ever read the results of some study that probably cost tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars to conduct, and thought, Someone paid money for this? Such as the one I read about some time ago, which showed that drivers of expensive cars were less likely to yield to pedestrians and bicyclists than drivers of older or cheaper cars. Wow, never could have figured that out on my own.

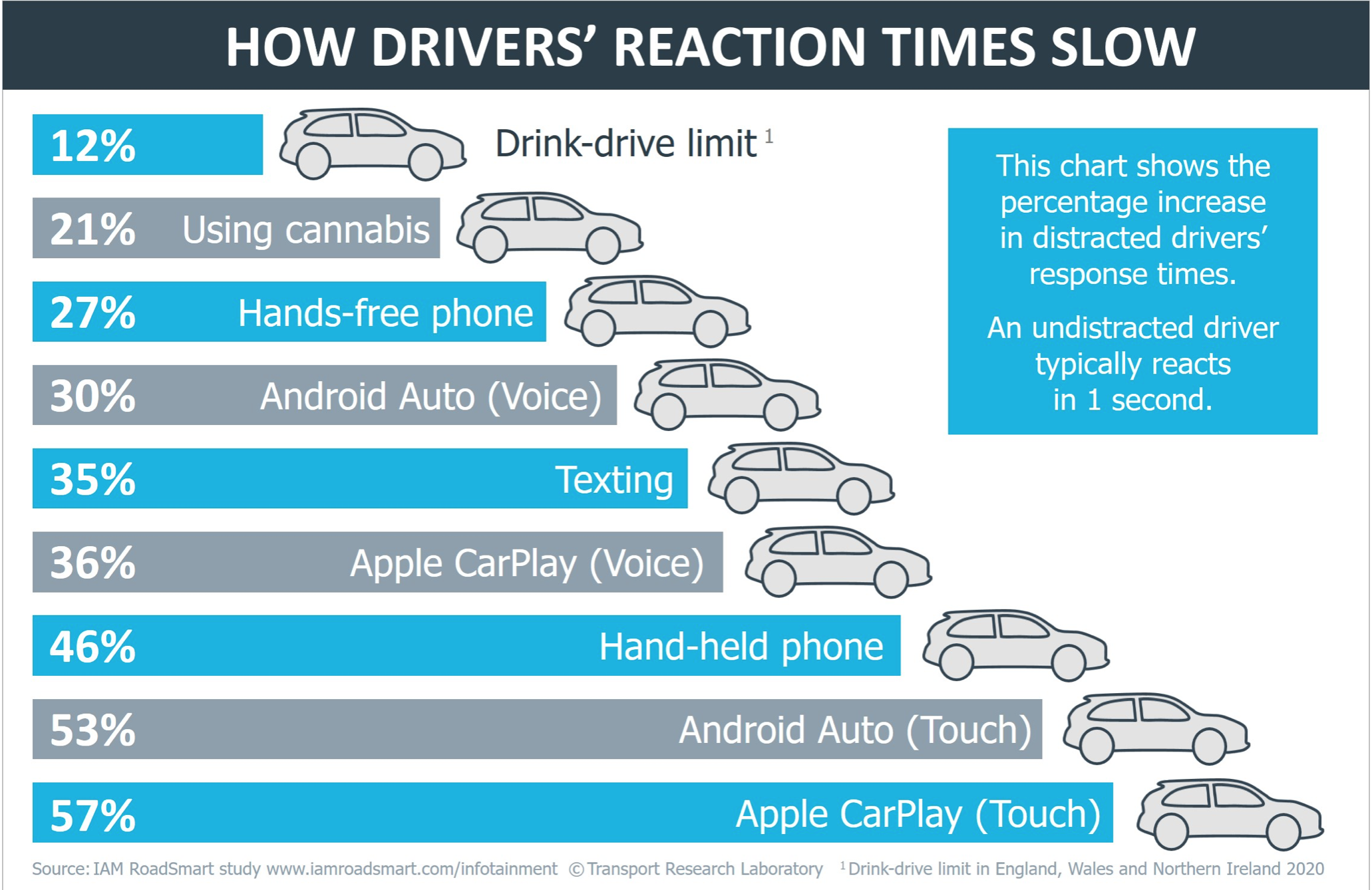

The latest is one run by the UK’s largest independent road-safety charity, IAM RoadSmart, which reveals that in-car touch-screen infotainment systems such Apple CarPlay and Android Auto drastically slow the reaction times of drivers. Stopping distances, lane control, and response to external stimuli all suffered even in comparison with texting.

Someone paid money for this?

Think back—those of you who can think back this far—to when the radio in your vehicle had two knobs and four or five manual station preset buttons. My FJ40 came with such a unit. To operate it I never had to take my eyes off the road. I could reach down and feel the on/off/volume knob, and tactilely count with a finger which station button I wanted to press.

Not so with the—rather ironically named when you think about it—touch screen. There is no way to tactilely determine where you are on a touch screen; you have to look at it. Combine that with the multiple functions and choices necessary to wade through and, well, as IAM RoadSmarts tests revealed, reaction times of tested drivers were worse than for those on cannabis and at the legal alcohol limit. Some drivers took their eyes off the road for as long as 16 seconds—that’s 500 yards at 70 miles per hour. Reaction times while choosing music through Spotify on Android Auto or Apple CarPlay were worse than for drivers who were texting.

It should be obvious by extrapolation that any operation controlled by touch screen—climate control, navigation, etc.—would have the same deleterious effect on reaction time. This, not any Luddite obtuseness, is why I strongly prefer mechanical controls for such accessories.

Incidentally, the same study showed that reaction times while using voice control for Android Auto and Apple CarPlay were also slower, albeit by not as much. Simply put, anything that takes your mind off driving is bad for your driving.

If you’d like to send me money for this revelatory post, email me for my Paypal address.

Once more, with feeling: Drum brakes are not "better off road."

It never fails to surprise me how persistent myths can be, even when there is an abundance of authoritative evidence to counter them.

A recent, otherwise informative and enjoyable article in a magazine I receive highlighted a classic four-wheel-drive vehicle from the 1960s. In describing the mechanicals, the writer noted that the brakes were drums on all four corners—still perfectly common in those years (my 1973 FJ40 came with all-drum brakes). While acknowledging this as outdated technology, the writer nevertheless went on to say (I’m paraphrasing), that drum brakes are less susceptible to loading up with debris off road, and that they stay cooler than disc brakes.

These claims are, respectively, badly misleading and utterly wrong.

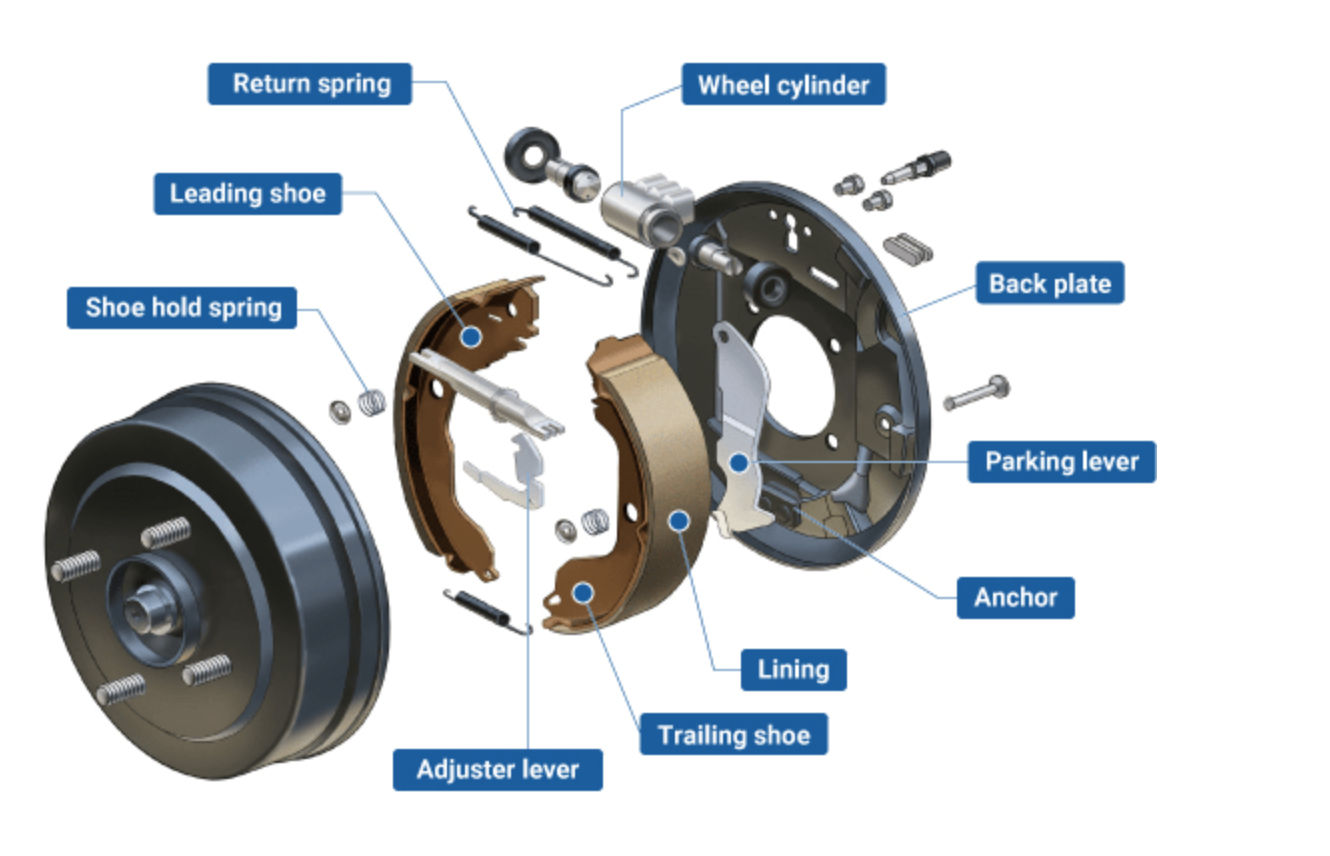

The claim that drum brakes are less likely to load up with debris—for example mud during an excursion through a mucky hole—might seem logical on the surface, since a disc brake’s rotor is completely exposed to the elements and is immediately doused with whatever comes its way. It is more difficult for gunk to work its way past a drum-brake’s backing plate and get into the mechanism. (No less an entity than Toyota Motor Corporation co-opted this line to excuse its parsimonious decision to retain rear drum brakes in the current Tacoma.)

The problem is that, once that gunk does get into a drum brake’s internals—and it will—it stays there until you disassemble it and clean it out, a time-consuming chore. Ask me how I know. A disc brake might squeal initially as slush impacts against the pad and disc, but it will quickly wipe itself clean, and if there is anything left a quick powerwash will take care of it. Drum brake shoes ride farther away from their contact surface on the drum, allowing debris to be caught between them.

The other claim, that drum brakes stay cooler than disc brakes, blithely ignores basic physics. Stopping a moving vehicle requires converting its kinetic energy into thermal energy. Period. All brake systems, whether drums or discs, have to absorb and then dissipate the exact same amount of heat when stopping an equivalent vehicle from an equivalent speed. Period. And while drum brakes absorb heat just fine—my FJ40, which now has four-wheel-disc brakes, stops no shorter than when it had all drums the first time you do so—they are are significantly worse at dissipating the heat they have absorbed. On a long, winding downhill road towing the 21-foot sloop I owned at the time the 40 still had stock brakes, the pedal would get progressively softer and less effective as brake fluid boiled into gas at the system’s wheel cylinders, where the drum brakes were retaining huge amounts of heat. Converting to disc brakes solved the issue as their rotors, exposed to the air, more rapidly dumped that heat.

So, once more, with feeling: Drum brakes are not “better off road.”

The big question: roof tent or ground tent?

The sleek but expensive Autohome Columbus in carbon fiber

Of all the requests for advice I receive, only choosing a vehicle seems to create more angst than the question of whether to buy a roof tent or a ground tent.

In simple economic terms this makes sense, since—especially if you decide on a roof tent—the outlay will likely be second only to the vehicle in terms of the hit on your overlanding budget. In fact I know people who have accomplished major journeys in vehicles that cost less than several roof tent models I can name.

But it’s also an important “lifestyle” choice, if you will, since carrying, deploying, and living with and in a ground tent is an entirely different proposition than doing so with a roof tent—even a roof tent with an add-on ground-floor room (or “mullet,” as a friend nicknamed the dangling appendage). So let’s look at the pros and cons of each.

Cost. Easy win for the ground tent here. The least expensive, made-in-China, soft-shell roof tents nudge $1,000. Premier products from Eezi-Awn, Tepui, iKamper, and others frequently top $3,000. And the size medium carbon-fiber hard-shell Columbus from Autohome will set you back a palpitation-inducing $5,600. By contrast, a 10’x10’, made-in-the-U.S. Springbar Traveler ground tent, one of the finest portable cabins on earth, costs $950. The 8’x8’ Turbo Tent Pine Deluxe 4 (from China), one of my favorite standing-headroom ground tents, is $495. And if you’re on a budget and don’t need standing headroom, there are dozens of options starting at under $200 from companies such as Slumberjack and Sierra Designs.

Classic, comfortable, and durable: the Springbar

Weight. Another win for the ground tent—with a couple of footnotes. That $5,600 carbon-fiber Autohome Columbus still weighs 92 pounds—and you’ll need a roof rack sturdy enough to support that weight while in motion and another 250-300 pounds when occupied. The soft-shell Front Runner “Featherlight” weighs 88 pounds. Larger and more feature-laden soft- and hard-shell roof tents typically weigh between 150 and 200 pounds. On the other hand, the 10’x10’ Springbar ground tent, made from substantial canvas and supported by substantial poles, weighs 62 pounds including poles and stakes. The 8’x8’ Pine Deluxe Turbo Tent weighs 42 pounds. Many other ground tents with as much interior volume as a large roof tent weigh less than 15 pounds. It’s true that roof tent weight includes a mattress, but that’s a matter of, at most, ten pounds.

The footnotes? Obviously the 62 pounds of the Springbar, or even the 42 pounds of the Pine Deluxe 4, is weight you’ll have to wrestle every time you pitch it—not so with a tent attached to the roof. Mount it once and forget it (unless you need to remove it between trips, either for handling and fuel economy or to avoid looking like an OVERLANDER every time you go grocery shopping). Importantly, the added weight of the roof tent is positioned in the worst possible place to add weight. Trust me that a 150-pound roof tent on an 80-pound roof rack will result in a noticeable difference in the on-road handling of even a substantial vehicle, and will make side slopes on trails more interesting.

Room. A runaway win for the ground tent. Even the most humongous roof tent is no larger than a good-sized backpacking tent. There are no roof tents with standing headroom for anyone taller than a four-year-old. Even a “mullet” only adds what is essentially a changing room. By contrast that Springbar Traveler will accommodate two full-size cots, plus a table and chairs or two smaller kid’s beds. You say you’re six foot five? You’ll still be able to stand up inside. The Pine Deluxe 4 is actually even taller at the peak.

In inclement weather, when you might be stuck inside during daylight hours, the contrast is even sharper (unless you’ve masochistically confined your ground tent to a backpacking model). Inside the 100 square feet of the Springbar you can walk around, sit across from your tentmate at a table to play cards or work, or catnap. Your luggage is out of the way under your cot. Cooking inside is easy. You can warm the space with a portable propane heater.

A Pine Deluxe 6 Turbo Tent, 10 feet square

Pitching. This is not as simple a question as it seems. Ground tents are intrinsically more involved to pitch, given unpacking and unfolding them, staking, running guylines, installing a fly, assembling cots or inflating mattresses, etc. Some are faster than others—the canopy of the Turbo Tent, for example, with its integral frame structure and spring-loaded joints, goes up in a flat minute. But you still need to add the fly and stakes. The Oz Tent is hyped for its rapid pitch, but it still requires stakes and guylines too. I got the pitching time for a Springbar down to a leisurely 15 minutes solo, or 10 with help.

Roof tents are universally marketed for their simple and rapid pitch, and for some models this is so. Hard-shell clam-shell models (hinged at the front), for example, are absurdly easy to deploy: You simply undo the latch(es) and hydraulic struts raise the roof. Done in five seconds. Some hard-shell box-style tents have the same system. Closing is just as simple and quick.

Soft-shell roof tents, however, vary widely in ease of deploying and, especially, stowing. The transit cover can be easy or difficult to remove before deploying the hinged floor and watching the canopy bloom. Window awnings need spring struts installed from inside, and if you’ve added a changing room you essentially have a ground tent to deal with as well, which must be attached to the frame of the tent at the top and staked out at the bottom. But it’s the process of stowing a soft-shell tent—and especially re-installing the transit cover—that can be the most time-consuming. I’ve done a lot of cursing while trying the stretch Velcroed covers back over several models I’ve reviewed. Nevertheless, on balance a ground tent will most likely take more time to pitch and stow than a roof tent.

A Technitop soft-shell roof tent with annex (or “mullet”)

Wind and precipitation resistance. This is more a function of the individual model rather than the type. A roof tent, of course, has the advantage of being bolted to a two or three-ton ground anchor, so there’s scant chance of it blowing away. And hard-shell roof tents, both the clam-shell and box style, tend to be superbly wind resistant. Soft-shell roof tents, on the other hand, can be okay or really bad. I’ve seen few that have adequately strong supports for the window and door awnings, and in general rain flies tend to be very poorly secured and prone to maddening flapping. Whether or not the tent itself is wind-resistant, it’s perched atop a vehicle with suspension and acts as an effective sail, so boat-like rocking can be a factor in getting a peaceful night’s sleep.

Any ground tent must be staked to be secure, and if possible I stake out guylines as well—I’ve never experienced a tent that was too wind-resistant. Staking can be problematic if not virtually impossible in several substrates: sand, mud, or slickrock, for example. The Springbar is the only big ground tent I’ve ever tried that comes with adequate stakes. Buy big ones; you won’t be sorry.

I’ve slept in roof tents that leaked and in ground tents that leaked, so again this is more a function of quality control than one style or the other.

You can’t beat the space in a ground tent

Sleeping comfort and bedding storage. Unless you suffer from claustrophobia, as my wife does (she once nearly knifed her way out of a smallish clam-shell tent after a midnight attack), actual comfort could be considered a tossup. Most roof tents come with thick, comfortable mattresses, on which you can use sleeping bags or standard bedding and pillows—which in many models can also be stored inside. Ventilation is generally excellent, and you’re up where breezes are unhindered and more free from dust than at ground level.

For any ground tent you must separately arrange (and store) cots or mattresses plus sleeping bags. With that said, a good cot topped with a thick Thermarest and a flannel-lined sleeping bag provides one of the most transcendent sleeps on the planet—right up there with being partway to the sky in a roof tent, like a kid in a tree fort. Take your pick. (One P.S.: With cots as your beds, it’s much easier to sleep outside on clear nights than it is to extract the mattress from a roof tent.)

Fuel economy/cargo space. Even the sleekest hard-shell roof tent will add significant aerodynamic drag, and with one of the big soft-shell designs on your rack you might as well be towing a drogue parachute. Clearly a ground tent stored inside the vehicle presents no such issues—but then a big ground tent might take up so much space you’ll be tempted to strap other gear to a roof rack. Win to the ground tent as long as you can avoid a roof load.

Other trade-offs. A roof tent is nice if the substrate is muddy, when a ground tent would wind up slimy outside and possibly in. Climb the ladder to the roof tent, remove your muddy shoes and store them in the pocket provided for just that purpose on many models, and your little home stays spic and span. On the other hand (you knew there’d be one), if the ground is muddy it means it’s been raining and is likely to rain more, and we’ve already discussed how much nicer it is to be holed up in a spacious ground tent. Take your pick.

In some situations, a ground tent can be left in place to reserve your campsite while you go exploring in the vehicle. A roof tent obviously needs to be put away completely to do so.

Rather counterintuitively, leveling the tent is easier when it’s attached to the vehicle, as you can use blocks or even rocks under the tires. A ground tent needs actual level ground. Also it’s usually easier to reorient a vehicle and roof tent than it is a staked and guyed ground tent, to account for shifting breezes.

A ground tent is way easier to move between vehicles, or to loan out to a friend.

Much has been made of the safety factor of a roof tent in regions with large mammalian predators, especially Africa. Honestly, after quite a few nights spent in both roof and ground tents on the continent, I find this a weak argument. Predators very, very rarely mess with tents, much less try to gain entrance. Yes, I’ve seen the YouTube video of the lions pawing at the ground tent, but I’ve also seen the one of the elephant disassembling the roof tent. Either is an extremely unlikely situation. And if you’re worried about creepy crawly things like snakes sliding into your ground tent and cozying up to you in the middle of the night, keep the door zipped shut.

So there you have it, and I’m sure there are other arguments for each. If you’re already a fan of one or the other you’ll find it easy to count up enough arguments in your favor. Otherwise, perhaps this list will help tip you one way or the other, depending on your own priorities.

Those Southern Ocean breezes . . .

What happens if you leave a 70-Series Land Cruiser exposed to the onshore Southern Ocean wind on the southwest coast of Tasmania, for 25 years or so? This . . . spotted in Trial Harbor.

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.