Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

Pelican's brilliant Air cases

On the off chance you haven’t noticed, except perhaps for the fantastically wealthy among us airline travel is no longer this:

Or this:

Or:

I could go on. These days we’re more likely to feel kinship with passengers on the ships that sailed to Van Diemen’s Land in the 19th century.

The latest erosion of our humanity concerns our luggage. Airlines have realized that we’ve been being massively selfish to want to bring along spurious stuff like, say, clothing, on our vacations. Some have gone so far as to grant us the enormous favor of “First Bag Free!” offers, that we might grovel with gratitude.

Then there are the carry-on items. (Brief interlude here: A vulture is getting on an airplane with a dead, stinking rabbit under his wing. The stewardess makes a face and says, “Uh, sir, may I check that for you?” And the vulture says, “No thanks, this is carrion.”)

Where was I? Right: I actually have no problem with reasonable carry-on restrictions. Way too much experience cringing in a aisle seat while someone tries to heave an overstuffed carry-on bag into the compartment directly over my head—endangering my skull and cervical vertebrae if he drops it—while viciously shoving aside my own smaller bag. Many of these bags clearly would not have fit in the little trial cage at the counter if anyone had challenged them.

Several years ago Roseann and I solved one problem by employing a pair of Pelican 1510 cases as our own carry-on bags. Completely crush-proof, we could store cameras and laptops inside with zero fear of damage from fellow passengers. They had rollers when needed, and served as decent seats in airports such as Nairobi International, where chairs are virtually non-existent. The capacity was reasonable but the case was significantly smaller than the overstuffed cheap bags, leaving our consciences untroubled. (Bonus: A Pelican case makes a fine impromptu safe in a vehicle when padlocked shut and cabled to a seat track.)

However, that protection had a cost. The 1510 weighs 13.6 pounds packed with nothing but atmosphere. Filled with Canon DSLR equipment mine was upwards of 33. And now many airlines are cracking down on carry-on weight, especially for intercontinental flights. We ran into it the first time last year when a desk agent insisted on weighing ours, expressed polite incredulity at mine, and forced us to stuff lenses and binoculars into our checked duffels. Not happy.

Some international airlines now list a maximum carry-on weight of 22 pounds—but on others and for certain destinations it’s as low as 15 pounds. That’s a Pelican 1510 and a paperback War and Peace. We had to find new luggage.

But how to do so without giving up the protection? I looked at the legendary Zero Halliburton aluminum cases; they weighed scarcely less than the Pelican, and were four times as expensive. No polycarbonate cases looked a tenth as stout as the Pelican; several I tried oil-canned at a bare touch. It began to look as though we’d have to go with soft cases and violently interdict anyone abusing them.

Then Pelican solved our problem for us, with the introduction of the Air line of cases. The new 1535 Air looks just like our 1510s, still has wheels, is virtually identical in volume—but weighs just 8.7 pounds, nearly a 40-percent reduction. And we’re still trying to figure out exactly where they lost the weight. It’s clear the material is somewhat lighter—pushing down on the middle of the lid results in a bit more flex than on the 1510—but the case retains virtually all its fragile-contents protection. And four pounds equals my Leica 10x40 binoculars plus a Lumix GX8 and 14-140mm lens, with a few ounces left over. Bravo Pelican.

The most interesting Land Rover I ever saw . .

. . . was not the fully kitted double-cab 130 in Namibia, or the 110 pickup veteran of the Rhino Charge in Kenya, or even the ex-Camel Trophy Defender owned by a friend.

It was in the spring of 1986. Roseann and I had been doing surveys to map Harris’s hawk nests in the deserts north of Tucson. We’d driven up Highway 79 to the Gila River area early one morning, and after several hours of glassing for nests stopped to refuel our Land Cruiser in the dusty little town of Florence, whose single claim to fame was and still is the massive state penitentiary on its outskirts. We pulled into a Circle K, and Roseann went in to buy a couple of Cokes while I filled up.

Out of the corner of my eye I saw a vehicle pull in to another pump, and did a double take. It was an ancient Series 1 Land Rover 86—essentially an impossible vehicle to exist in Florence, Arizona, where anything not from the Big Three would have still been looked on even then as deeply suspicious and probably Democrat.

That it was local became apparent when the driver, a craggy 60-ish gentleman, got out, dressed in faded Wranglers, a tattered western work shirt, and a generic feed cap. I walked over and said hi, which he returned in a drawl as thick as gear oil. Yes, he lived there, yes, he’d owned the Land Rover for a couple decades, although, “I can’t remember where it’s made—somewhere in Europe I think.” As I silently gaped at this, he continued, “When I need parts the fellas at the NAPA here get them for me. Never had any trouble with it though.” He raised the hood and started the engine, which ticked away with a barely audible murmer through its oil-bath filter.

The Land Rover was dead original—even the tires looked like they might have rolled it out of Solihull. Winch. Canvas hood. The only additions were a rifle rack and a CB radio.

“That your Tiyota?” He pronounced it tie-ota. Nodded when I nodded. “Mmm-hmm. Nice looking vee-hicle.”

Improbable enough already, but then—look closely at the photo here, scanned from a black-and-white print that is the only record I have of the encounter. See the bottle mounted in front of the windscreen on the driver’s side? Look even more closely and you might spot the pipe leading from it, through the fender, and attached to a fitting on the exhaust pipe.

“That? That’s my gopher getter.” Said with not a little pride.

It turned out that Mr. . . . I never got his name . . . derived a fair amount of his income from eradicating the “gophers”—actually pocket gophers—that plagued the nearby farmers, burrowing up from underneath their crops. The bottle contained some viscous and evil-looking brown poison—I never got its name either—which gravity-fed through the tube and was emulsified in the exhaust stream, whence it was pumped via a hose into the holes of the unlucky gophers.

“My own invention! Kills ‘em real quick. No reason for 'em to suffer.”

I was not sure how he had determined this, but . . .

All the nearby landowners had his phone number as well as his CB handle, he said. Nope, no business name, just . . . whatever his name was. Paid in cash per dead gopher.

After a few more pleasantries, he said, “Well, you take care, young fella. Be seein’ ya.”

But we never did again.

Vintage Land Cruiser ads

Probably no car manufacturer will ever exceed the brilliance of Volkswagen with its early Beetle advertisements. However, Toyota did some good work with the FJ40 back in the day. I like the pointed reference to the spare on the hood here.

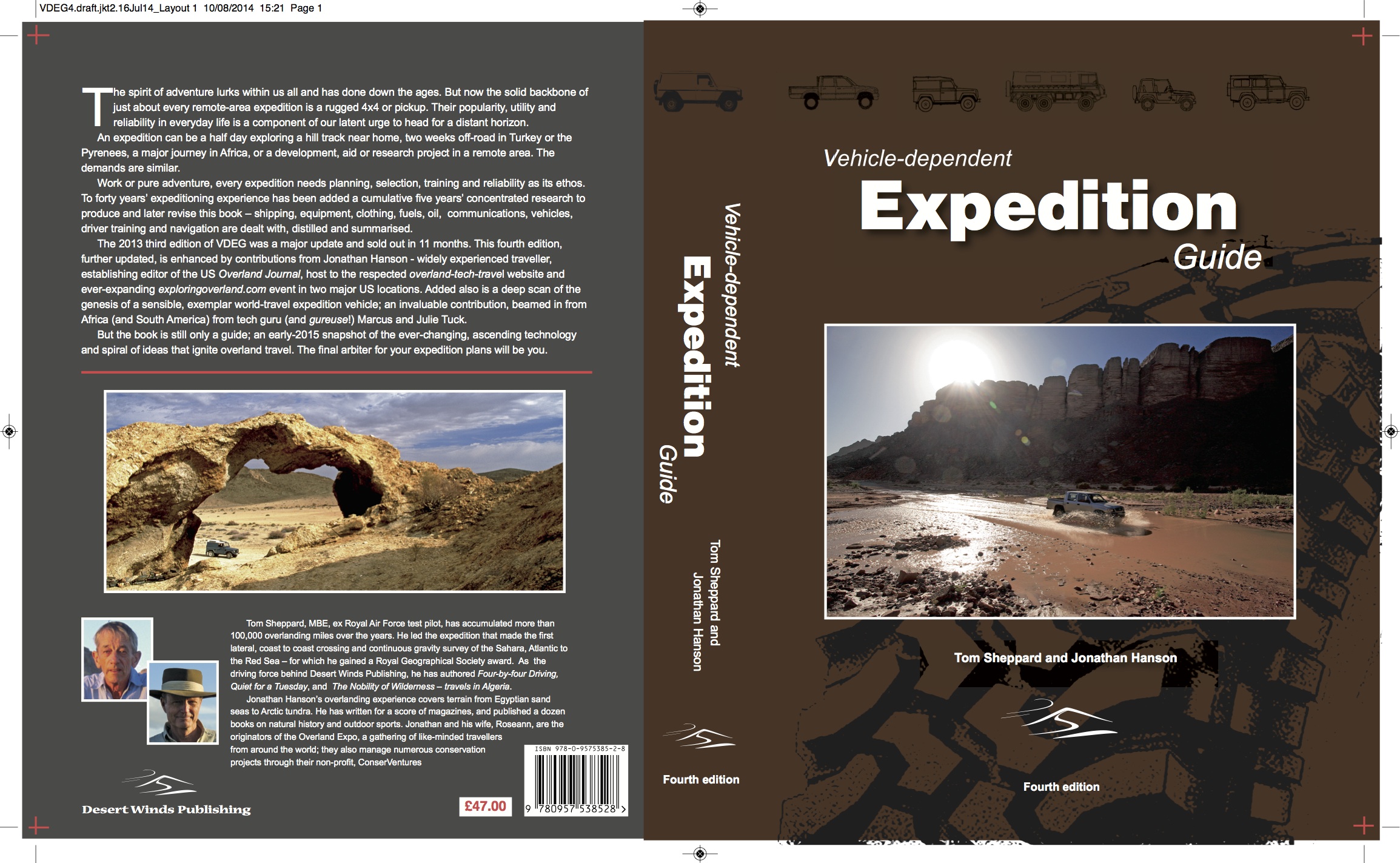

Running out of VDEGs

We are down to fewer than 20 (edit-10) copies of the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide, and do not know when we will receive more stock. If you've been thinking of ordering a copy, please do so soon! Available here.

Update: It appears we will have a new shipment some time in August.

The very best recovery tool is . . .

I know, I know . . . there are several much more glamorous bits of equipment with which to decorate a 4WD vehicle—many that are well worth having. But I can’t think of any with the same combination of, 1) Affordability, 2) Reliability, 3) Versatility, and 4) Simplicity, as this most basic of tools.

A great many vehicle boggings occur when two or more tires spin down through whatever substrate you are trying to negotiate, until depth and friction prevent them climbing out. Assuming you’ve already aired down, the simplest way to extract yourself is to scoop out four ramps for the tires to climb. Even if you have a set of MaxTrax to employ, it’s smart to give them a head start with some digging.

You can also use a shovel to add substrate to a hole you have to drive through. If you need to fill a bigger hole with rocks, a shovel will help you pry half-buried candidates out of the ground. If you high-center on a rock or dirt, the shovel can help free you. And of course a shovel is handy for innumerable other tasks, which can’t be said for most recovery-specific products.

So what sort of shovel to have? That’s in many ways up to personal preference. However, I’ve found several characteristics that I think make a shovel better suited for recovery work.

Length: Some experts recommend a full-length handle, to enable you to reach all the way under a vehicle that might need sand cleared from its chassis, for example. However, a long shovel is awkward for most other uses in the field, and much more of a pain to carry in a vehicle. I like one no longer than about 40 inches total, and have found that this length actually works better in a majority of cirumstances.

Handle: I strongly prefer a T or D handle, and if you haven’t tried one I bet you’ll agree with me. A handle perpendicular to the shaft offers far more comfort, control, and power when punching it under a tire to clear sand, and it’s far easier to put sideways torque on the blade when needed.

Shaft: It’s hard to criticize an all-welded-steel shovel such as the Wolverine DH15DP above, which I wrote about here. For sheer indestructibility it has no peer. However, a proper ash or hickory shaft/handle will be perfectly sturdy and is nicer to use in heat or cold.

Combination tools: Not a fan. Again this is personal preference, but I’ve found the tools that combine a single handle with, for example, a removeable shovel blade, axe head, and sledge to be generally heavy and not very good as any individual tool. The axe function, in particular, is invariably miserably balanced and completely lacking in grace. An axe should be a living thing—and, frankly, that balance and grace is a safety issue when you’re swinging a sharp blade. Buy yourself a proper axe and leave the shovel as a shovel.

Folding entrenching tool: Definitely, absolutely better than nothing, but c’mon—you’re not carrying it in an A.L.I.C.E. pack with MREs, you’ve got a vehicle. Get a real shovel. If you really want or need something that compact get one of the brilliant surplus German one-piece shovels like this:

. . . which typically have one side of the blade sharpened as a makeshift axe (or a nasty self-defense weapon that doesn’t look like a weapon to authorities in authoritarian countries).

My favorite recovery shovel is about as prosaic as you can get: It’s the Land Rover T-handled tool that comes in the evocatively named “Pioneer Kit,” which also includes a very functional take-down pickaxe. You’ve seen these clipped to the front wing of inumerable Series vehicles. My first close encounter with one was in Namibia, on a guide’s battered Series IIA that also sported an entire sofa bolted to the roof for tourists to ride on. The shovel was so well-used in Namib sand that the blade was visibly shortened, and shiny as glass.

The Pioneer Kit is available through UK surplus stores online; occasionally as NOS (New Old Stock). If you happen to be there you can find them for less at one of the myriad four-wheel-drive shows. The shovel’s blade extends to a long shank that encloses nearly half the wood (ash?) shaft. If anything the blade is a bit thicker than it needs to be. In any case it will demonstrably last through years of abuse in the Namib, probably a lot longer if you aren’t constantly needing to dig out a Land Rover with a sofa on the roof.

U.S. manufacturer A.M. Leonard offers a forged D-handle shovel that looks excellent, although I’ve not seen one in person. Ditto with U.K. maker Richard Carter.

Whatever you decide on, make sure you actually keep it with you. I give you my situation a few weeks ago, camped on the North Rim of the Grand Canyon with a few friends. Roseann and I had both our Tacoma/Four Wheel Camper and the FJ40 along, and when she needed to dig out an existing fire pit she asked me where she could find a shovel.

"Uh . . . "

Fortunately our friends were better prepared.

Update: Correspondent John Wilson tells me that the BLM in the Owyhee region (Oregon, Nevada, Idaho) requires one to carry a full-length shovel, presumably because it is easier to use to put out a spreading campfire. My own advice would be to make sure your damn campfire can't spread in the first place, but thanks to John for the heads up.

The Lion Man

If you're not familiar with him, his work—and his well-used vehicles—this interview on the Leisure Wheels site with Dr. Flip Stander, who studies desert lions in the Namib, is well worth the read. A donation would be well worth it, too. No, your eyes aren't deceiving you: That is a Toyota Hilux in the photo above, with a Land Rover roof and windshield Siamesed on top. Stander put over 750,000 kilometers on it before the South African Land Cruiser Club donated a Land Cruiser to his project.

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.