Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

Pinnacle product: the Antiluce latch

Can a tailgate latch with one moving part qualify as a pinnacle product? Absolutely. In fact, that’s exactly why it does.

I’m not sure when the “Antiluce” (get it?) latch was invented—Google suffered a rare fail in not finding me something like an Antiluce Appreciation Society with monthly meetings at the Queen’s Head in Tunbridge Wells. I know they were on Series II Land Rovers because I’ve seen them. Photos of JUE 477, the very first production Land Rover, seem to show a type of Antiluce latch, perhaps refined as production progressed. For all I know it could have been invented decades before that. A small British company named Burrafirm, later purchased by Albert Jagger Limited, seems to have held the patent for quite some time.

The Antiluce is so simple that it would take the proverbial one thousand words to describe it, so if you’re not familiar with it look at the photos and it will be clear. It’s essentially a toggle latch—flip it horizontal to close the tailgate and the hole in the hasp fits over it. Then flip it vertical, push in on the tailgate to snug it against its weather strip, and the stepped opening in the Antiluce automatically takes up the slack and ensures a rattle-free fit. With new weatherstrip the latch might only drop down to the first or second step, but as the weatherstrip beds in or wears, the latch simply drops down a step at a time to maintain consistent tension. Brilliant. Its natural tendency is to obey gravity, so if the tailgate flexes over rough roads the pin will only snug itself, not loosen or come unfastened.

The drop-down tailgate on my FJ40 closes with over-center draw latches, which are bulkier, heavier, fiddlier, and no better. If I ever do a complete restoration on the Land Cruiser I plan to convert it to Antiluce latches. They’re available from numerous sources including all the major Land Rover stores, and could easily be adapted to other uses on custom trailer compartments or cabinetry. The threaded shaft can be had in several lengths, and there are weld-on versions too. At around $30, it’s possibly the cheapest pinnacle product on earth.

The five best modifications . . . to leave off your expedition vehicle

Expedition travel is a different universe than weekend four-wheeling. When you’re just out for a few days near home—camping, challenging a few trails—breaking down is no more than an inconvenience. But if you’ve embarked on a long journey far from familiar territory, perhaps in another country or on another continent, a breakdown can endanger the trip—or even your safety if you’re traveling solo and are tens or hundreds of miles from assistance. For journeys such as this, your priorities regarding vehicle modifications and accessories need to change, from an emphasis on maximum 4WD performance (and, let’s be honest, maximum looks) to reliability and durability. A lot of the products that enhance the former can seriously impact the latter. Here are a few of the most important.

Big tires. Everyone loves the look of big, aggressive tires on a 4x4, and in certain situations they have advantages in ground clearance, traction, and the ability to successfully climb ledges. But big, heavy tires extract a heavy price. They put massive additional stress on your suspension, steering components, and bearings. They hurt fuel economy and retard acceleration—and if you install higher-ratio differential gears in an attempt to compensate for these downsides, you’ll simply weaken the pinion gear, which has to be reduced in size to gain the higher ratio. Larger-diameter and heavier tires also increase braking distances. Remember that Land Rovers conquered Africa on skinny 7.50 x 16 tires, and Land Cruisers conquered Australia on the same size. Besides, if you destroy one of your 38s in Botswana I guarantee you won’t find a replacement in Maun. They know better there. For more details on the downsides of big tires, see here.

Installing higher ratio ring and pinion gears results in a smaller, weaker pinion gear.

Big suspension lift. As with tires, there are some advantages to a raised suspension for rock crawling or mud bogging. Not on an expedition. You want to keep your center of gravity as low as possible to ensure maximum fuel economy and safe handling while carrying the equipment and rations needed for a long journey. Big suspension lifts increase angles on rod ends and driveshaft joints, leading to premature wear. You’ve probably seen photos of the Camel Trophy Land Rovers that challenged some of the toughest terrain on the planet—they all rode on stock-height suspension. If you really think you need some lift, keep it to a couple of inches. The expedition experts at ARB know this—their Old Man Emu suspension kits are all in the two-inch range.

Race shocks. Along with a suspension lift, many owners install long-travel shocks modeled after racing versions, with all-metal heim-joint ends, external-bypass tubes, and remote reservoirs. Shocks like this are designed to deal with the kind of high-speed, high-amplitude movement common in off-road races—exactly what you’re not going to be doing on a long journey in a loaded vehicle. You’re better off using a simple shock with enough oil capacity to stay cool after a full day of driving over washboard or rutted roads and trails. Standard rubber bushings last longer and are far easier to replace than heim joints, and help dampen road vibrations. Exposed chrome shafts quickly become sandblasted in the bush; they should be shielded or completely covered with a sheath or bellows.

The best expedition shock I’ve ever used is the Koni Heavy Track Raid, an utterly boring-looking thing next to the racer models, but with a huge oil capacity capable of soaking up mile after mile of abuse under a fully loaded Land Rover 110. ARB’s (Old Man Emu) BP51 is another excellent shock, employing internal bypass valves that allow adjustment of both compression and rebound without the exposed bits of external pypass tubes. Some BP51 models, it appears, come with heim joints; I’d avoid those. Sadly neither of these shocks is available for my FJ40 or I’d have them on it (although the standard OME Nitrocharger has performed well for me for decades).

The Koni Heavy Track Raid relies on robust twin-tube design and massive oil volume to handle torturous conditions.

Wheel spacers. A wheel spacer is a disk—usually aluminum—that fits between the hub and the wheel to increase track width and reduce lateral load transfer, which can fractionally help handling and stability. They give your truck a more aggressive look, too. Unfortunately, they also put significant extra stress on wheel bearings, since as you move the wheel farther away from the bearing you’re essentially lengthening a very strong lever. You’re also increasing the scrub radius, which is the distance between where the pivot point of the kingpin intersects the ground and the center of the tread, as well as increasing the kingpin offset. All of this affects the steering and suspension negatively, and will wear components you do not want to have to replace in a spot where “Amazon” only refers to a large river.

Every time I criticize wheel spacers I get emails from guys (you know who you are) who’ve had them on for X-hundred thousand miles and never had a problem. I don’t doubt this. But physics is physics, and putting extra leverage on your wheel bearings and steering components does them no good, period. (I know a guy who smoked two packs of cigarettes a day and lived to 80, too. Doesn’t prove it’s a good idea.)

“High-performance” air intakes. Intake systems that replace the stock air filter with one designed—or at least hyped—to produce more horsepower are frequently much worse at actually filtering air, and are often more vulnerable to water intrusion during a crossing. Those advertised horsepower gains are measured on a dyno—about as far from expedition reality as possible. The truth is, most factory intake systems are carefully routed to ingest cold outside air while minimizing the danger of water ingress. You can, if you choose, install a snorkel, which contrary to belief does not automatically turn your vehicle into a submarine, but does help get the intake above some ground-level dust.

Roof rack. Okay, I said five, but here’s a bonus. Do without a roof rack if you can. Ah, but what about the Camel Trophy Land Rovers I just mentioned? They looked awesome under those racks piled high with jerry cans and PelicanPelican cases, right? True, but, first, the CT vehicles usually had two team members plus two journalists inside; they were operating in extremely remote terrain, and and simply had to carry extra gear on the roof. More important, those vehicles all too frequently ended up on their sides during demanding special tasks. You don’t want to do that, because you won’t have 15 other Camel Trophy vehicles to help you get back on all four wheels.

Excess roof loads negatively affect handling and fuel economy, and everything strapped up there is vulnerable to casual theft. It’s even bad for braking: Weight up high tends to pitch the vehicle forward under braking, unloading the rear tires. If you absolutely need a roof rack, keep the load as light as possible—the weight of the rack itself plus, say, a tent is about maximum for safety’s sake. Some of the current minimalist aluminum racks from Front Runner and ARB don’t add much mass or bulk themselves, as long as they’re not loaded up with 300 pounds worth of jerry cans and Hi-Lifts and solar hot shower systems.

Remember, on a long, remote journey, reliability should be your number one through five priority. Add on all the accessories you like that won’t affect that, but the best approach to most critical driveline components is to stay as close to stock as possible.

Proof in the pudding: We successfully negotiated the Abu Moharek sand sea in three Land cruisers with 1) near-stock-size tires, 2) stock suspension, 3) factory (raised) air intakes, 4) no wheel spacers, and 5) lightly loaded roof racks.

(A version of this article first appeared in Tread magazine.)

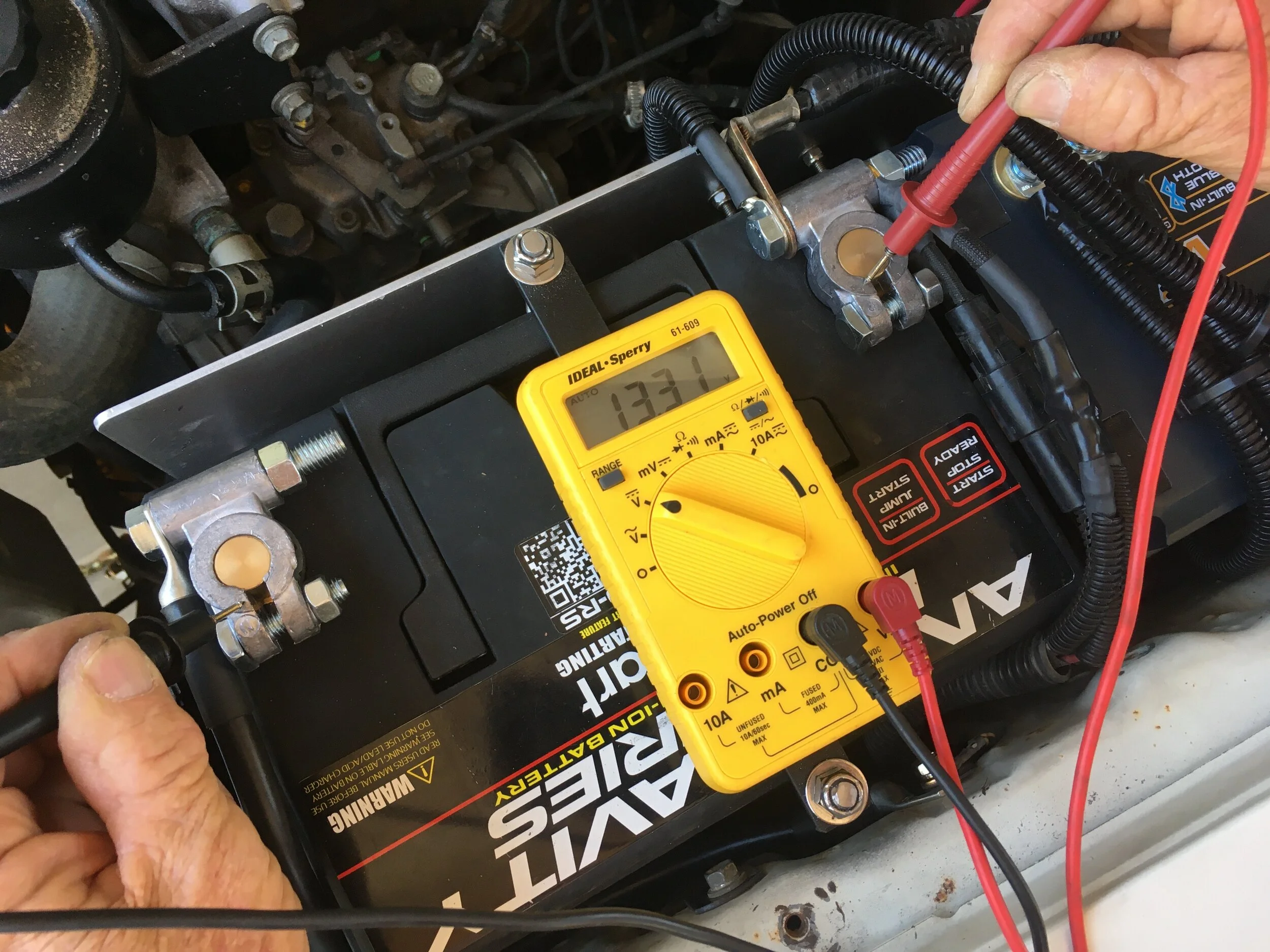

LiFePO4 voltage stability

After an extended interval collecting the bits for the LiFePO4 dual-battery system I’m installing in our Troopy, I’m finally buttoning up the project, which will appear first in OutdoorX4. The delay gave me a chance to experience in a small way one of the benefits of LiFePO4 batteries, which is their superior voltage stability when left idle. I received this battery from AntiGravity in early February, and it has sat since then. Upon installing it I checked the voltage before starting the engine, with the result here. That’s impressive.

Hella horns

The only car I’ve ever owned that had decent factory horns was a Porsche 911SC, which was equipped with proper Autobahn blasters to move inattentive slower cars into the right lane right now. All others—and especially all the Japanese makes—needed serious upgrades to perform at a level I consider acceptable. I don’t use my horn very often, but when I do I want it to capture its target’s undivided attention. This has become significantly more important in the age of texting—which studies have show to be more dangerous than drunk driving. Why? Drunk drivers, at least, are generally paying attention because they know they’re drunk and they don’t want to alert the police. Texting by definition requires one to remove all one’s attention from the road.

Thus all of our vehicles carry Hella horns of one model or another. They’re affordable, starting around $20 or so, and all have an authoritarian tone. My favorites are the twin or triple-trumpet air-powered models, which have a lovely teeth-on-edge screech, but the lesser models such as the ones here are still excellent.

These went on Roseann’s mother’s RAV4, which we have taken over since she gave up driving at 90 and is now allowing us to chauffeur her around town. The stock horn on this vehicle was even worse than most Japanese horns, which tend to sound like sheep bleating. This one sounded like an asthmatic sheep bleating.

Of course, being a modern vehicle, removing the “grille” on the RAV to access the horns actually involved peeling off the entire plastic front end of the thing . . .

. . . which, thanks to a helpful YouTube video describing the location of the hidden fasteners, only took about ten minutes.

After that it was easy. The Hellas require a separate ground wire, which I simply connected to each horn’s mounting bolt. The result is a huge improvement. I’m going to go hunt for texters.

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.