Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

So a hitch ball is okay as a recovery point? (But I saw it on the Internet!)

A couple weeks ago Gigglepin 4x4, a UK company that specializes in high-quality 4x4 recovery gear, especially for competition, posted a video on Facebook that showed someone attaching one of their rapid-deployment Hook Link recovery hooks to . . . a hitch ball.

The reaction was swift. Several people, including me, posted replies saying any suggestion to use a tow ball for recovery was inconceivably irresponsible. One of the first inviolable lessons any 4x4 training school with which I’m familiar teaches is to never, ever use a tow ball as a recovery point.

The next day the company responded . . . by reporting my post (and, I presume, others as well) as spam and having it removed.

Then something interesting happened. The original video, as far as I can tell, was taken down. Instead, the company posted another video on their website explaining “what we actually meant” in the first one. In it, the spokesman first demonstrates attaching a Hook Link and strap to a proper recovery point on a Discovery, and notes that it is, “Much safer than placing the strap or rope over the tow ball.” He then says that using the Hook Link and strap on a tow ball is “ideal for recoveries on the road and light duties around the workshop,” and adds that it’s “not ideal” for extreme recovery situations. Confused yet? He then says, even more confusingly, that the MSA (Motorsports South Africa) rule book allows some UK-style tow balls—which, unlike typical U.S. versions, are usually flanged and fastened with two M16 bolts—to be used for recovery in racing.

Contradictions aside, let’s look at this. First, as far as I recall (since I can no longer find it), the original video contained no such explanations or caveats; it simply showed the Hook-Link being snapped over a hitch ball, quite clearly as a suggested application. The opportunities for this to be interpreted as a universally acceptable practice by inexperienced 4x4 drivers/Facebook users are rife.

Second, a friend who called my attention to the first video followed up and contacted a well-known supplier of this type of tow ball in England, to ask for their stance on the use of such balls for recovery.

The response:

“Towbars are designed to pull the safe rated load that they were tested and type-approved at in a smooth and controlled manner. They are not designed to be subjected to any sharp impact or snatch, using them for this purpose is most likely to overload and cause damage, possibly invisible to the naked eye, that may not become immediately apparent but weeks or months later may cause failure and pose a danger to other road users. Using a towbar in this manner would be classed as outside of their intended use and would invalidate any warranties.”

There’s another potential factor at work in such a scenario. I couldn’t find any specs of the Hook-Link that listed the width of the neck of the hook. It appears to be around two inches or more. If the neck is larger than the tow ball over which one hooks it, a sudden jolt and slack could pop the hook off the top of the ball. In the U.S. standard tow balls start at 1 7/8 inches in diameter.

I noticed one more confusing aspect to the Hook Link. The spokesman noted there are two versions of the product, identical in size but employing different aluminum alloys in construction. The model made from 6082 is rated at 4.5 tons, the one in 7075 to 6.5 tons. I assumed he was referring to a metric ton (2,204 pounds) and, indeed, the Hook-Link shown on the website is stamped “Break strain 4500kg”—which is 9,920 pounds, and 4.5 times 2,204 equals 9,918 pounds. But . . . “break strain?” That doesn’t sound like our familiar working load limit (WLL) with a 2X or 3X (or greater) safety factor; that sounds like the point at which things might come apart precipitously. Perhaps it’s a matter of cross-Atlantic nomenclature, but here we like to see both a WLL and a separate minimum breaking strength (MBS).

I’m going to restate the rule: Don’t use a tow ball—any tow ball—as a recovery point. Period.

What about alternative methods for employing a receiver hitch as a recovery point? Many articles and trainers suggest inserting the loop of a recovery strap into the receiver tube and fastening it with the hitch pin. This has the advantage of securely anchoring the end of the strap or rope.

However, look at the diagram below, from Dougal Hiscock, a mechanical engineer at at Engen Consulting in New Zealand, which shows the relative stresses exerted on a tow ball and a hitch pin subjected to a 5,096 kilogram (11,235 pound) steady pull. The stress is three times higher on the pin due to its smaller diameter. The pin is also subjected to a three-point bending load, from the strap in the middle of the pin and the through-points on the side of the receiver. When towing a trailer using a hitch insert the pin is subject only to sheer loads, as the square receiver insert rides closely against the wall of the tube. A wide strap or rope, such as the one illustrated, might reduce the focus of this bending stress, but it will still be much higher than that exerted by a receiver tube under the same load.

The only acceptable way to employ a receiver for recovery is to use a receiver shackle insert and shackle to attach the kinetic strap or rope. Even then, I much prefer a dedicated shackle mount on a bumper designed for recovery duty, or a chassis-mounted recovery ring.

Toyota's new (not for the U.S.!) 3.3-liter V6 turbodiesel

Along with the near simultaneous announcements that Toyota would be pulling the Land Cruiser from the U.S. Market while introducing the completely redesigned 300 Series Land Cruiser elsewhere, the company also announced a brand new engine for the updated model. Replacing the existing 4.5-liter, twin-turbo V8 is a 3.3-liter, twin sequential turbo V6. This is Toyota’s first diesel V6.

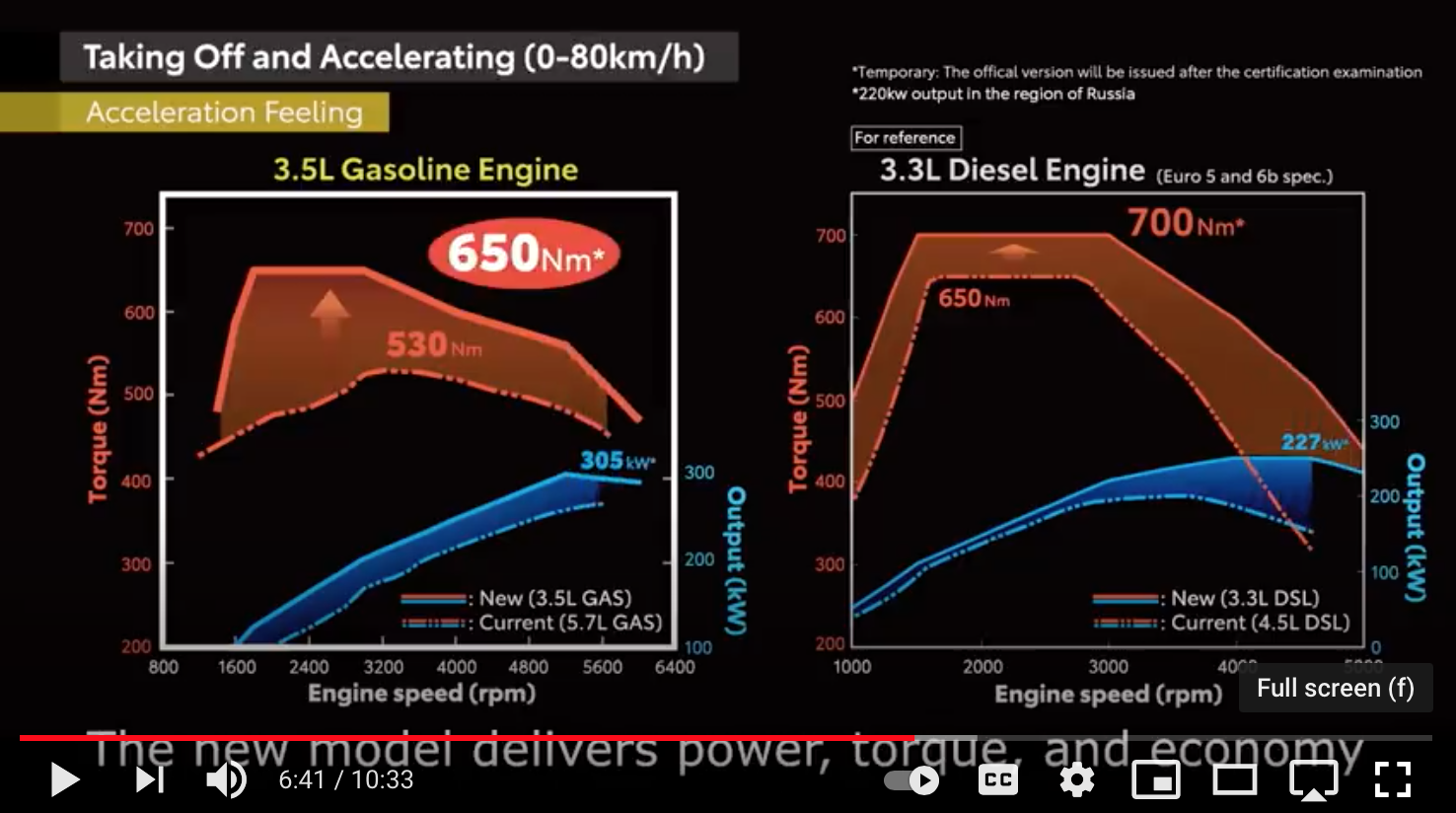

Reflecting the advances in turbodiesel technology, the new engine boasts increased power and torque compared to its significantly larger predecessor—304 horsepower and 516 lb./ft. compared to 268 horsepower and 480 lb./ft.

Just as importantly, and contrary to the fears of those who predicted the smaller engine would have a torque peak higher in the RPM range, the 3.3’s curve peaks in more or less exactly the same range as the 4.5, from 1,500 to 2,900 rpm. Note the chart on the right below.

The new engine should exhibit significantly decreased turbo lag, thanks both the the sequential turbo configuration (in which one is set up to provide immediate boost while the other takes over higher in the rev range) and the “hot vee” arrangement of the exhaust.

In contrast to standard V engine construction, in which the intake manifold sits between the cylinder banks and the exhaust exits under the sides of the V, the hot vee turns everything around, siting the exhaust manifolds between the cylinder banks. This drastically shortens the run from the exhaust ports to the turbos.

The 4.5 was known for—depending on your point of view—underwhelming specific power output, or being admirably under-stressed for heavy-duty use. The 3.3 is obviously tuned to a higher level, but much of that might be attributed to the configuration. The 4.5 also had a few problems, at least early on, with disappointing oil consumption (although I only read about this in connection with the single-turbo version in the 70-Series vehicles).

I’ve not yet read anything regarding the new engine’s fuel-delivery system—or, more to the point for overland travelers who rightly view the 70-Series vehicles as the ultimate global expedition platforms—whether or not it will be installed in the Troop Carrier and its brethren.

There are tent stakes, and tent stakes . . .

This . . . is the latter.

If you’ve read my work for more than a few weeks, you probably know how much I hate cheap tents (see here if not). It should be banally axiomatic that your tent is your home away from home, your last refuge from wind, rain, snow, and insects. It makes no sense to economize on a piece of equipment that, at the very least, can mean the difference between a peaceful or sleepless night, and at the worst, could be your key to survival.

The same goes for the stakes with which you secure that tent (or awning). The finest, most aerodynamic four-season tent on earth is worthless if it’s secured with flimsy, undersized stakes, and the same goes for the expensive batwing awning on your overland truck, which can pluck inadequate stakes out of the hardest substrate when a bit of a blow lifts its sail-like surface area. During every Overland Expo Roseann and I ran we struggled with and cajoled and threatened vendors to tie down their blue EZ-Up awnings with something more than the flimsy aluminum toothpicks they came with, which I could—and did, as a demonstration—bend between my teeth.

These stakes will not bend between my teeth.

We already own a set of very decent stakes for the Eezi-Awn Bat 270 awning on our Troopy—one set of thick round steel pegs for hard ground, and another of wide, curved aluminum for sand.

Recently, however, I was browsing the Major Surplus site and came across a pack of six French military steel stakes for $29.95. They looked awesome, so I ordered a set. And they are indeed awesome: cruciform steel, seventeen inches long and 1.45 pounds each, with a welded hook. I immediately ordered another set. They should suffice for any kind of substrate.

These stakes will secure any tent not capable of enclosing a trapeze act. No, I won’t carry them on my bicycle for use with my Hilleberg Anjan GT, but for bigger shelters? Take my advice and get a set; you’ll sleep better.

The Morgan CX-T . . .

Just in case you thought it was no longer possible to buy an off-pavement vehicle as uncomfortable as an FJ40 or Series III Land Rover . . .

From NewsPress UK:

Morgan unveils the Plus Four CX-T, a car with adventure at its core. A vehicle with capability not yet witnessed on a Morgan sports car, it opens up the possibility of routes, landscapes and destinations inaccessible by Morgan cars until now.

The Morgan Plus Four CX-T is inspired by Morgan’s well documented history of competing in all-terrain endurance trials. As early as 1911, Morgan sports cars were competing and winning in trials competitions, and this spirit of adventure has been key to shaping the Morgan brand ever since. The more adventurous journeys that are frequently undertaken by Morgan customers all over the world have further fuelled the desire for Morgan to imagine the Plus Four CX-T.

Following the launch of the Plus Four in 2020, Morgan partnered with Rally Raid UK, renowned creator of Dakar race cars, to jointly design and engineer the Plus Four CX-T. One of the aims of the project is to demonstrate the capability and durability of Morgan’s new CX-Generation platform, along with the Plus Four upon which the CX-T is based.

Just eight vehicles will be built, priced at £170,000 plus local taxes and supplied in full overland specification, with each customer having the opportunity to work alongside Morgan’s design team to specify their own CX-T. Every Plus Four CX-T is built at Morgan’s factory in Malvern, Worcestershire, before undergoing the final preparation and setup at Rally Raid UK’s own workshop facilities. Morgan’s design and engineering team have worked alongside Rally Raid UK throughout the programme to define the concept, specification, technical attributes, and aesthetic of the model.

More here if you’re intrigued. I am, in a twisted sort of way.

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.