Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

Quality, seen and unseen

For several years I’ve stored my “in-town” automotive tools in a modest older Snap-on rolling chest combination (which I bought used). But it’s been getting really crowded recently, and I’ve been thinking about augmenting or replacing it. The decade-old Craftsman chest out at our desert place is larger, but I didn’t want to just swap the two as I still need a full complement of tools out there as well.

By sheer coincidence I was at an acquaintance’s house last week to deliver a gate opener I’d sold him, and it turned out he had recently bought the entire remnant stock of Kobalt tool chests from the local Lowe’s home improvement stores. Kobalt had been the chain’s store brand for years, but recently they switched to Craftsman—which, as you might know, is now owned by Stanley Black and Decker rather than Sears. In my mind this switch is actually a step down: Recent made-in-China Craftsman tools that I’ve examined in their packaging show noticeably poorer finish than the older made-in-America products, poorer in fact than the few Kobalt tools I’ve purchased to review.

Anyway, my friend had scored several dozen of Kobalt’s top-of-the-line stainless-steel-clad tool chests, and quickly unloaded all of them at fire sale prices. He had exactly one left, and it happened to be a tall, narrow, 27-inch-wide model, which is the only configuration that will fit in the in-town garage. So I bought it for a song.

Back at home I had to pull the drawers to unload it and get it into position. And that gave me the opportunity to look past the beautiful stainless exterior and the nifty soft-close drawers. What I noticed made me pull apart that plain old red Snap-on chest to examine it as well. And that’s where significant differences showed up. Drawers out, the Snap-on cabinet was noticeably heavier and more torsionally rigid than the top box on the Kobalt. Where Snap-on used nuts and bolts and spot welds to assemble pieces, the Kobalt had been assembled almost exclusively with pop rivets—in fact I found several stems from those rivets still inside the cabinet. Both brands incorporate smooth roller-bearing drawers, but when I re-installed the Snap-on drawers they each slotted perfectly into their slides and snicked home effortlessly, while the Kobalt’s drawers proved to be a real pain to get properly lined up. I had to carefully fit each side in each slide to prevent it simply falling out, then guide the assembly in until it clicked back together—after which, I should note, each worked perfectly, including the soft-close function.

Don’t get me wrong: The Kobalt chest is a very nice item and I’m glad I bought it, especially at the price. I’m sure it will serve my amateur mechanic needs adequately, as I’m only in those drawers a dozen times per month, rather than dozens of times per day as a pro would be. But it was clear that the Snap-on chest would hold up to that kind of use far better than the Kobalt would. (And I managed to squeeze the Snap-on chest into another corner of the garage.) Snap-on certainly puts a hefty price premium on its products, and it is inarguable that a good part of that premium is strictly due to the name and cachet, but at least you get the excess you pay for.

In a larger context, it points out the obvious fact that external looks aren’t everything. It’s the engineering underneath that determines quality.

Classic Kit: The capstan winch

If you’ve ever crewed (or skippered) a sailboat longer than 20 feet or so, you’ve probably used a capstan winch to control lines such as the jib and spinnaker sheets. A basic capstan winch comprises a vertical drum geared so it will only turn one way (always clockwise on a sailboat). When you wrap the line around the drum (again, clockwise) two or three times, you can more easily control the forceful pull of the sail. The friction of the wraps helps prevent the line being pulled away from you. If you need more power to sheet in a sail in a breeze, a a fitting on top of the drum allows you to insert a crank for extra leverage. There are more elaborate capstan winches with two speeds, self-tailing mechanisms—and electrically powered winches that eliminate the need for manual cranking.

For many years, a capstan winch could also be ordered as a factory option on Land Rovers and a few other vehicles. Visually the vehicle-mounted capstan winch was very similar to our sailboat winch; however, it was powered through a gearset from a driveshaft usually connected directly to the vehicle’s crankshaft via a sliding coupler. The worm-drive gearset reduced the 600 or 700 rpm of an idling engine crankshaft to just a dozen or so turns per minute of the drum (which, curiously, rotates counterclockwise on every one I’ve seen).

A capstan winch at LR-Winches. Engagement lever is at upper right. The rope is led under the roller from the anchor or object to be moved.

A capstan winch has an entirely different method of operation from the common, horizontal-drum electric, hydraulic, or even PTO winch with which we’re familiar. You don’t store line on the capstan, and it cannot use steel cable. Instead you carry a separate, low stretch rope—traditionally 3/4-inch manila or an equivalent natural fiber—of whatever length you chose, with a hook on one end.

Let’s say you’re driving your Series II 88 along a forest track and you come across a downed tree blocking the way. Pulling it out of the path would go like this:

Position the vehicle so the winch has a clear route to drag the tree off the path. Leave the engine idling, transmission in neutral (obviously), parking brake on and, if possible, the wheels chocked as well. (If you have a hand throttle you can bump up the engine rpm a bit.) Wrap a strap around the tree and connect your winch rope to it with its hook. Take the free end of the rope back to the vehicle, run it under the roller guide and around the drum three or four times counterclockwise in an ascending spiral, then lay the free end of the rope off to the left of the vehicle as you’re facing the front. With the coils of the rope around the drum still loose, engage the lever to connect the drum to the gearset and the drum will begin turning slowly—but the loose rope will simply slip around it. Now stand back from the vehicle a few feet and pull on the free and of the rope to tighten the wraps around the drum. The drum will grab the rope and begin pulling on the downed tree, as you take in the rope fed you by the winch. You now control the speed and engagement of the winch simply by pulling or slacking off on the rope to tighten or loosen it around the drum. Once the tree is off the path, let the rope go slack, disengage the gearset with the lever, and de-rig. It’s that simple.

Of course you can also connect the rope to a standing tree or another vehicle to free yours if it is bogged; however, since the capstan winch requires someone standing outside the vehicle to operate the winch, it’s nearly mandatory to have a second person in the driver’s seat to steer the vehicle and stop it once it’s free. Solo vehicle recovery with a capstan winch can be a very dicey operation indeed.

Consider the situation pictured below. Tom Sheppard was in Mali in 1978, en route to Timbuktu, driving his Land Rover Velar—that’s right, the original prototype of the Range Rover—and towing a trailer full of fuel and water, when a section of mud proved a bit deeper and stickier than was apparent from the driver’s seat.

Tom’s Range Rover was equipped with a Fairey capstan winch cleverly hidden behind the grille—note the horizontal roller on the bumper. To deploy it one simply unscrewed the center grille section, a matter of a couple of minutes. However, Tom was, as is common with him, traveling solo. Therefore he first unloaded all 21 (!) jerry cans from the trailer, decoupled it from the Range Rover, and recovered the Range Rover with aluminum sand (i.e. mud) ladders. Then he positioned the Range Rover in a spot where he could use the capstan winch to recover the trailer, re-connect it to the Range Rover, reload all 21 jerry cans, and continue on his way.

(Tom’s story made me remember the tour Roseann and I got of the Gaydon Museum, courtesy Land Rover historian extraordinaire, Roger Crathorne. I looked up one of the photos, which shows, in addition to Roger and me, one of the Range Rovers used on the 1971/72 Trans-Americas Expedition—and there was a capstan winch peeking out from behind the grille.)

The capstan winch’s labor-intensive method of operation, combined with its modest power—most were rated for around 3,000 pounds, as was the rope used on them—saw them fade from popularity with the increasing availability of horizontal-drum electric winches of considerably higher rating. Yet the capstan had its advantages. It could work all day without overheating or stressing the vehicle’s electric system, and its line capacity was essentially unlimited—if you needed to rig a 200-foot pull, all you needed was a 220-foot rope. And that labor-intensive method of operation gave the operator instant control over the procedure—let off on the rope tension and the pull stops instantly. The capstan winch, with its leisurely speed, hands-on attitude, and natural-fiber rope, always struck me as, well, the friendly winch compared to the whining, straining, ozone-smelling electric winches of today (hugely capable though they certainly are). Go ahead, laugh.

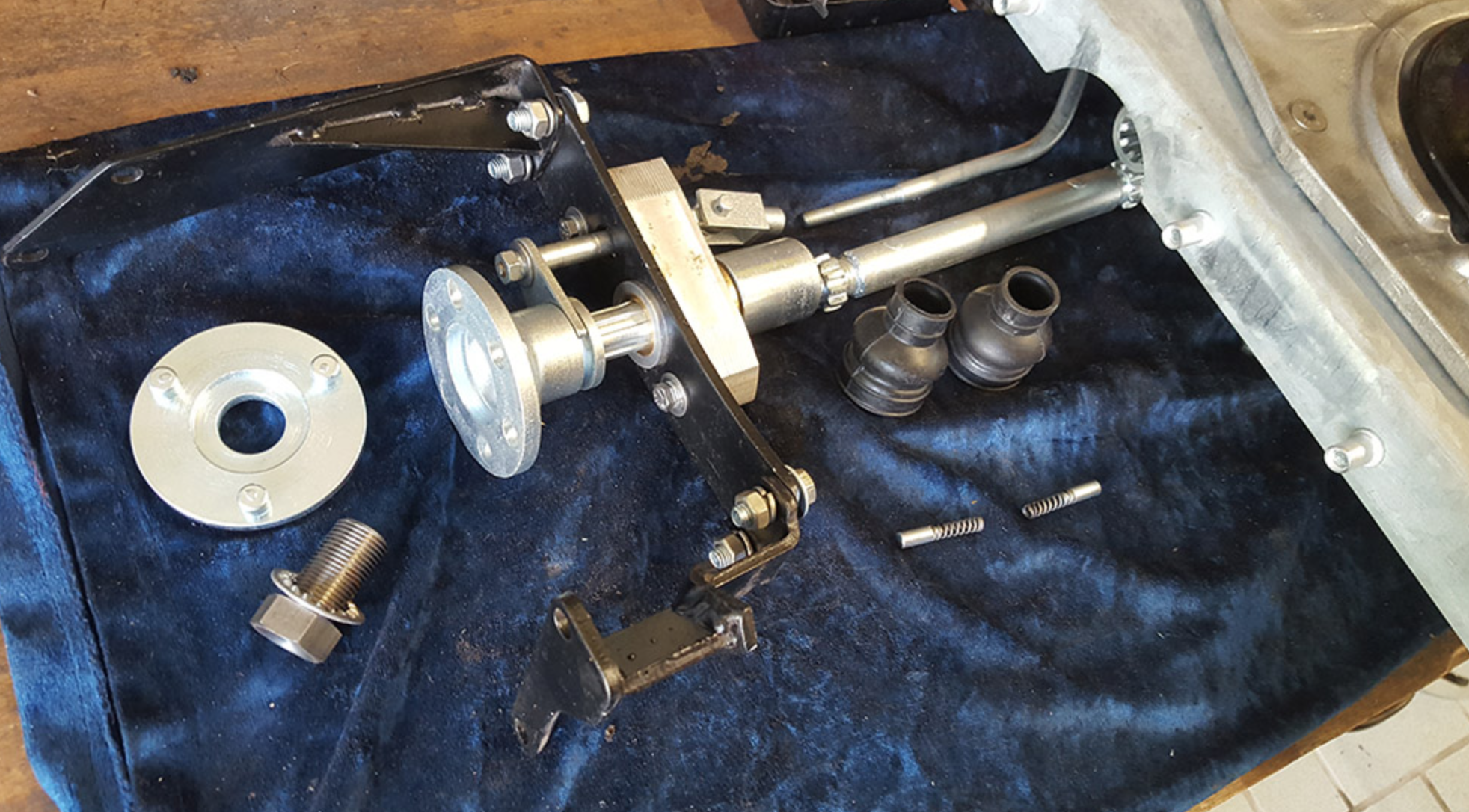

This is the driveshaft and engagement mechanism that allows the capstan to be powered off the front of the vehicle’s engine.

You can still, very occasionally, spot a vehicle equipped with a capstan winch—virtually always a Series Land Rover. If you own a Series Land Rover and have a hankering for a curious and historical piece of very useful equipment, you can still buy one (or parts for one) through sources such as the experts at LR-Winches (where most of these images originated). You can even buy a synthetic rope suitable for a capstan winch, from LR-Bits.co.

But I’d recommend sticking with the manila rope. It’s just . . . friendlier.

For a . . . curious . . . installation of a capstan winch, see here.

JL Wrangler frame issues

Photo: Brett Stevens

The folks over at Jalopnik have a good and extremely important article about the issues some owners are having with welds on JL Wranglers. The critical issue is the weld that holds the track bar to the frame, and the article includes photos and a video of the problem.

The track bar is what locates the front axle side to side, so if it goes so does directional control and steering—not a good thing.

If you own a JL Wrangler you will probably be receiving information about this, but in the meantime you might want to take action yourself. Reportedly FCA has issued a stop-sale order until the matter is addressed.

The new Defender appears, sort of . . .

Currently making the rounds of forums, at last, is a photo of a heavily disguised test prototype of the much-awaited, much-delayed, resurrected and re-invented Land Rover Defender.

The speculation about this vehicle has been on a level like nothing I’ve seen in the four-wheel-drive universe, even beyond the theories that swirled around Jeep’s re-designed Wrangler.

The Wrangler rumor mill terrified aficionados with hints that the new model would lose its solid front axle for independent suspension—perhaps even on the rear axle as well. Then we heard its separate, fully boxed chassis would be abandoned for unibody construction, rendering it in the faithful’s eyes no more than a glorified jacked-up sedan.

In the event, the new JL Wrangler stayed built the way God intended Jeeps to be built: solid front and rear axles, body-on-fully-boxed-frame construction. Parent company FCA managed to incorporate modern safety and convenience features into a decades-old blueprint, and the new Wrangler remains a superb choice for extended travel in rough country.

Tragically, at least for thousands of traditionalist Land Rover faithful, the exact same rumors (or perhaps I should say rumours) proved well-founded as Jaguar/Land Rover gradually released details of the new Defender. The 2020 replacement for the 70-year-old expedition icon will ride on all-independent suspension and will be built on aluminum-intensive unibody architecture shared with other Jaguar/Land Rover products.

Thus one thing is clear: The old Defender is dead and buried (recent outrageous £150,000 factory specials notwithstanding). No more will Land Rover ship CKD (Complete Knock Down) Defenders in crates to be assembled in developing-world countries and pressed into rough service in the remotest backwaters of the Realm. No more will adventurous owners boast of accomplishing major drivetrain rebuilds with hand tools outside an Angolan village. The new Defender will be a completely different vehicle than the old one. The question is, will it be a better vehicle?

J/LR swears the new Defender will be more capable off-road than its predecessor—not at all an outrageous claim given the huge advancements in traction control systems since the relatively primitive system installed in the last generation. And, honestly, it won’t be difficult to exceed the capabilities of the pre-traction-control Defenders, which relied solely on gearing and compliant suspension to negotiate challenging terrain, thanks to Land Rover’s obstinate decades-long refusal to fit cross-axle differential locks. Even the independent suspension will only be a handicap in certain situations, such as when both front wheels compress upon hitting an obstacle, reducing clearance to the fixed front differential. It will certainly enhance ride and handling. And while traditionalists might not like it, unibody construction actually results in a vehicle with far higher torsional rigidity than a vehicle riding on a separate frame, even a fully boxed one. You simply lose the ability to unbolt the body from the chassis with your sockets and wrenches. And repairing collision or trail damage on a unibody vehicle is considerably more involved.

So the capability will be there. Whether J/LR offers the new Defender in suitably basic form to satisfy those who eschew leather and carpet and 10-inch entertainment screens in their overland vehicles—as well as to create an affordable version—remains to be seen.

One area where I suspect the company will get it right is styling—not that there’s much to tell from the disguised test vehicle. After the PR disaster that was the DC100, I’m willing to bet J/LR went to great lengths to evoke the original’s styling without being overtly retro. I predict it will look properly sturdy and adventurous.

Thus we’ll have a capable vehicle that looks the part. The only remaining big question involves market placement. Will Jaguar/Land Rover aim for existing Defender owners, or will they exploit that iconic model name and shove it toward the upscale end of buyers, those who want the look and the rugged association, but who wouldn’t dream of actually shipping their rugged-looking vehicle around the Darien Gap or across the Strait of Gibraltar and exploring another continent?

If you look at sales history I think the answer is clear. The last Defender—the solid-axle, separate frame, bolted-together genuine expedition machine, went extinct for one reason: It stopped selling. Why would Land Rover aim at the exact same customers with the new one?

In some ways the decision will be out of their hands. A technologically advanced vehicle, built largely out of aluminum, with all-independent suspension, sophisticated traction-control and safety systems, and advanced powerplants, is going to be expensive to produce and will cost a lot to buy. I’ll wager the base price of the new Defender 110 (or whatever it will be called) will be substantially above that of the already dear Wrangler Rubicon Unlimited. The temptation to just go with that and load it up with leather and carpet and entertainment screens will be powerful.

I’ll wager further that ads for the new Defender will be stoked with historical family references, and heavy on images in rainforests and sand dunes. Just which magazines those ads appear in will betray the direction the new Defender will take—towards the real jungle or the concrete one.

The versatile 1/4-inch ratchet . . .

The ratchet and socket set is the most critical component of your tool kit. It’s what comes out when things need attention that are held on to the vehicle with actual nuts and bolts, rather than just trim screws or plastic press fittings. Important things, in other words. I’ve always maintained it’s the part of your kit you should spend the most money on, to get the absolute highest quality. Of all the tools I’ve broken over the years, the majority by far have been cheap sockets that split, or cheap ratchets that jammed or broke altogether.

Most owners—me included—start out with a 3/8ths-inch ratchet and socket set (the 3/8ths refers to the diameter of the anvil, the square peg on the ratchet to which you attach the sockets). A 3/8ths set will comfortably handle bolts or nuts from about 9mm or 5/16ths inch up to 19mm or 3/4 inch. That’s suited for a lot of medium-sized repairs—replacing fan or serpentine belts, water pumps, radiators, etc. Above that you really should step up to a 1/2-inch ratchet, which is able to handle larger sockets for fittings such as those on suspension components, which need more torque to remove or fasten securely.

Thus for a long time my automotive tool kit has included a 3/8ths-inch ratchet and socket set for general work and a 1/2-inch set for major repairs. And that worked just fine. But lately I’ve been rethinking. Why? Several reasons.

Even a 3/8ths ratchet can be a bit long and bulky when working in tight spaces on fasteners smaller than 11 or 12mm. Yes, you can add a short-handled ratchet to the kit, but the head will still be just as bulky. And your 3/8ths socket set will probably have a lot of overlap with your 1/2-inch set. Typically the former will include sockets up to about 19mm, and the latter will include sockets down to 12mm. I’d rather use a 1/2-inch ratchet for that 19mm nut, yet a 1/2-inch ratchet is silly overkill for any 12mm bolt or nut I’ve ever encountered.

Enter the 1/4-inch ratchet. It’s smaller all around, able to fit into spaces no 3/8ths equivalent could. You can argue that the ratcheting mechanism is inevitably weaker as well, but consider two things: First, there is only so much torque necessary for even a 12 or 13mm fastener; second, a high-quality ratchet will withstand force comfortably in excess of any you’re likely to need. I’ve yet to meet a 12mm or even 13mm nut that I couldn’t remove with a 1/4-inch ratchet. And it will be far handier for smaller sizes.

Additionally, a 1/4-inch ratchet and socket set will cost less than a larger one, so you can go for higher quality. Finally, the 1/4-inch set will be lighter and take up less space, a surprisingly real consideration even in something such as our Troop Carrier, the tool bin of which is approaching maximum capacity and the GVWR of which is approaching, period.

So I’ve been wondering if a versatile combination might be a 1/4-inch set with sockets ranging from very small, say 4 or 5mm, up to about 13mm, and a 1/2-inch set with sockets from 12 or 13mm up to whatever you like—my current set goes up to 32mm. The slight overlap would mean that if you ever did run into a recalcitrant 12 or 13mm bolt while using the 1/4-inch kit, you could switch up to the 1/2-inch.

I have a nice mixed set of 1/4-inch stuff, but this scheme was a perfect opportunity to spend money on tools. I like investigating brands new to me, and my friend, driving trainer extraordinaire Graham Jackson, is fond of the German brand Proxxon, so I looked them up on Amazon, and ordered the 23280 49-piece “Precision Engineer’s” 1/4-inch drive set.

The first thing that impresssed me was the box it came in. While plastic rather than metal, it had decent sliding latches rather than the usual flimsy snap latches with stressed-plastic hinges, which invariably fail. A nice touch.

Inside I first examined the ratchet itself. The mechanism was a fine 72-tooth unit. Check. Push-button release, check. Lever-operated reversing switch, check. Perfect. The offset head is supposed to ease access to tight spaces. Not sure about that one.

The selection of sockets was very good. Standard sockets from 4mm to 13mm—perfect. They’re forged from chrome vanadium with a double-nickel and single chrome layer finish for corrosion resistance. They of course employ a copy of Snap-on’s Flank Drive system to help grip rounded off nuts (and to avoid rounding them off). A bonus was a comprehensive selection of bits for either the ratchet or the included driver: Screwdriver bits, hex bits, and Torx bits. Five sockets for external Torx fittings. There was even a little selection of angled allen keys, 1.25 to 3mm. The set included two ratchet extensions—one of which included a (removable) sliding T-bar fitting—and a universal joint.

The only flaw I found was the paucity of deep sockets—just four of them, in 6, 7, 8, and 10mm. Odd. Why not a full complement up to 13mm? I would have traded the external Torx sockets for them. As it was there was no space in the tray for additional sockets. But . . . what’s this? There appeared to be some voids in the box under the molded tray. Indeed, when I lifted it out there were several generous gaps.

I called the U.S. Proxxon headquarters. They told me they don’t directly import the hand tools sets, only power tools (I bought mine through a third party dealer). However, when I told them what I was trying to do they generously offered to special-order the sockets I wanted. So I filled in the deep sockets and bought a flexible drive extension as well. All those plus a Snap-on flex-head 1/4-inch ratchet fit underneath the tray.

I guess I need to clean up those holes.

Now I had a comprehensive 1/4-inch socket and ratchet set with the bonus of the driver bits and handle. As expected, it was significantly more compact than an equivalent in 3/8ths. The last task was to make it easier to get the molded tray out when I wanted the stuff in the bottom. So I Dremelled two slots in the tray, and ran a piece of flat 1/2-inch webbing through them and under the tray, leaving the ends loose on top. It’s now easy to pull the tray free.

Our Troop Carrier has a comprehensive set of tools, but they live in a cabinet under a bench that is somewhat of a pain to get to. I’ve been wanting to have a more convenient tool kit for small repairs and adjustments. This Proxxon set, with its combination of sockets and bits, should fill that role perfectly—and it’s compact enough to fit behind a seat.

Hmm . . . I wonder if I should order another two or three sets?

Epilogue: Regarding my idea that a 1/4-inch socket set combined with a 1/2-inch set might be all one needs for just about any job: Proxxon sells a kit (23286) that combines just that, with sockets from 4mm all the way to 34mm. Impressive. Just add some deep sockets and a breaker bar.

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.